Thoreau’s Buddhism

A presentation to the White Heron Sangha June 23 2013

Henry David Thoreau was born July 12, 1817 and died at 45 years of age on May 6, 1862. His name is a household word, especially among those of us who grew up during the 1960’s, when his two most famous works, Walden and “Civil Disobedience” offered compelling guides to non-conformity, self-reliance, appreciation of nature, reduction of one’s environmental footprint, opposition to war and injustice and spiritual quest.

Although not widely appreciated during his life, since the late 19th century Thoreau’s works have become classics, admired by later writers, assigned in schools, and the subject of a burgeoning scholarly industry. He produced more than 20 volumes in a dense and quirky literary style, at times pompous and bombastic, at others intimate and funny.

Thoreau shared a philosophical outlook with his patron and early teacher Ralph Waldo Emerson and others of his circle known as Transcendentalists. Like the European Romantic idealists, they abjured organized religion but shared a reverence and love for Nature and espoused a spirituality grounded in personal experience of a higher, non-physical reality. They were excited by the novelty of Eastern religions whose texts and practices were beginning to be disseminated in the West during the early 19th century. Thoreau admired the austerity and asceticism of Eastern mystics. He probably died a virgin and earned a meager living as schoolmaster, lecturer and writer.

Unlike Emerson, he was an outdoorsman in practice as well as theory. He developed the skills of surveying, farming, and construction and became a precise observer and recorder of natural phenomena like climate variation, the dissemination of seeds and the succession of plants. Later in his life he made significant contributions to the budding science of ecology and the early environmentalist movement.

Thoreau’s writings and example have exerted changing influences throughout my life. “Economy,” the first chapter of Walden, helped persuade me and my wife Jan to leave the ratrace and move “back to the land” from New York City in 1970 to try our luck at living the good life in the wilds of British Columbia by growing our own food and reducing our physical needs to the basics of shelter and clothing.

Nine years later and considerably disillusioned about Thoreau’s advice as it applied to a husband and a father and to my own capacities as a woodsman, I returned with my family to the States to complete an unfinished Phd dissertation. It’s topic was the relation of the pastoral ideal to the life cycle”in particular the irrelevance of that ideal to householders of middle age whose job it is to “hold up the world.”

But even after learning the limitations of Thoreau’s seductive praise of life outside the system, I found value in his teachings. As I pursued a career as an English professor, his observations about war, nature, and spirituality remained central to my research into religious violence, outdoor education, and the connections among experience, thinking and writing. I developed courses at Cal Poly that included frequent excursions beyond the classroom onto the ten thousand acres of University land that housed a remarkable wealth of natural and cultural resources:

Thoreau’s words provided encouragement and direction:

“Where is the literature which gives expression to Nature? He would be a poet who could impress the winds and streams into his service, to speak for him …whose words were so true, and fresh, and natural that they would appear to expand like the buds at the approach of spring, though they lay half smothered between two musty leaves in a library… ” [1]

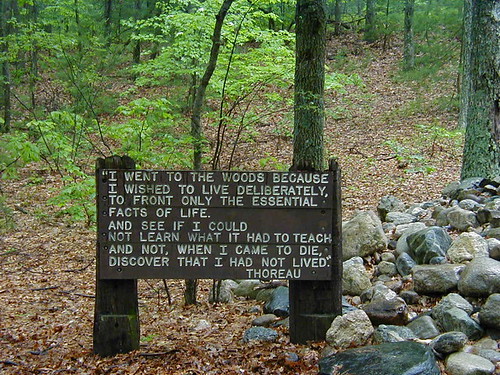

In 2003, while attending a conference of the Association for the Study of Literature and the Environment in Boston, I visited the headquarters of the Thoreau Society near Walden Pond and made a pilgrimage to the site of the cabin where Thoreau spent two years and gathered the material for his book.

I added a stone to the pile of thousands left in tribute by fellow pilgrims, and then walked down to the nearby bank.

It was a rainy spring day and the normally crowded shoreline was deserted.

Without a swimsuit, I immersed myself in its deep placid waters.

During the years I was teaching these courses, I used to make a habit of sleeping out one night a week at a different location on Cal Poly Land in order to complete my own version of the journaling assignment I gave to students. I’d bring along a copy of Walden and found myself returning to certain passages, which like scriptural verses, always took on fresh significance. The power of these utterances has grown since my retirement from teaching and attendance at the White Heron Sangha.

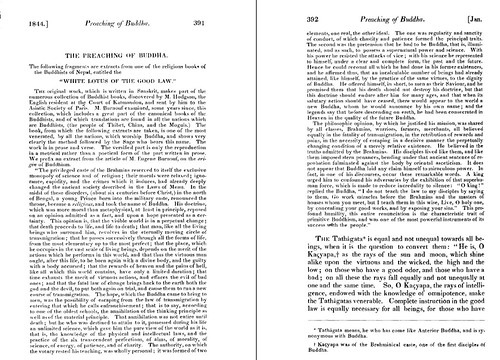

When I was invited to give a talk to this group a few months ago, the topic of Thoreau and Buddhism seemed like a possibility, so I googled those two words and was amazed by what appeared on the screen: “IN JANUARY OF 1844, the first excerpts of the Lotus Sutra to appear in the United States were published in Ralph Waldo Emerson’s literary journal, The Dial. The editor and translator was the twenty-six-year-old Henry David Thoreau.” This was in a 1992 article in Tricycle by Wendell Piez.[2]

Another link took me to an excerpt from a 1981 book by Rick Fields about the history of Buddhism in America called How the Swans Came to the Lake: “Thoreau had gone to a great deal of trouble to present this quintessential mahayan sutra [the Lotus Sutra] to American readers. He had himself translated it from the French of Eugene Burnof’s L’introduction a l’histoire du Buddhisme indien, which had just appeared in Paris.”[3]

That was enough to commit me to the topic and list it by the deadline in the Sangha’s newsletter. I searched for the 1844 translation online to find what had gone through Thoreau’s mind as he studied the Sutra but could only find brief excerpts. Then I came across this: “IN THE WINTER 1992 issue of Tricycle, I reaffirmed one of the most cherished claims of American Buddhism. The first known translation from a Buddhist sutra into English, I wrote, was [by]¦ Henry David Thoreau. I was following a long tradition of scholarship, but ¦. The translator wasn’t Thoreau. It was Elizabeth Palmer Peabody””another member of the Transcendentalist circle, owner of a Boston bookstore and publisher. The disarming title of the article: “Anonymous was a Woman”Again.”[4]

But even though Thoreau was not the translator, he was engaged with this Sutra as editor and led me to it for the first time. I expected that it would teach me something about his inspiration and that he would illuminate it for me.

The Lotus Sutra, I discovered, was originally written in Sanskrit between 100 B.C.E. and 200 C.E. and translated into Chinese in 286 C.E. In it, the Buddha tells the assembly that his earlier teachings were provisional. ¦ and that this sutra presents the final, highest teaching, and supersedes all others. The Buddha is dharmakaya— the unity of all things and beings, unmanifested, beyond existence or nonexistence, unbound by time and space.[5] A theme expressed throughout the sutra is that all beings [including women] may attain Buddhahood and reach Nirvana. According to Piez, this is “a teaching wholly consonant with the tolerance of the American religious spirit represented by Emerson and Thoreau.”[6]

The complete Sutra seems long, repetitious and often opaque for an uninitiated reader, but the material chosen for The Dial is quite accessible.

It’s likely that this passage, known as “The Parable of the Medicinal Herbs,” would have appealed to Thoreau for its vivid description of vegetation as well as for its use of natural symbols for a higher reality.

I who am the king of the law, I who am born in the world, and who govern existence, I explain the law to creatures, after having recognized their inclinations. ¦ It is¦ as if a cloud, raising itself above the universe, covered it entirely, hiding all the earth. ¦ Spreading in a uniform manner an immense mass of water, and resplendent with the lightnings which escape from its sides, it makes the earth rejoice. And the medicinal plants which have burst from the surface of this earth, the herbs, the bushes, the kings of the forest, little and great trees; the different seeds, and everything which makes verdure all the vegetables which are found in the mountains, in the caverns, and in the groves; the herbs, the bushes, the trees, this cloud fills them with joy, it spreads joy upon the dry earth, and it moistens the medicinal plants; and this homogeneous water of the cloud, the herbs and the bushes plump up, every one according to its force and its object.[7]

Thoreau regards such teachings of the Sutras and of the earlier Vedas as his own thirst-quenching sustenance. In chapter 16 of Walden, he exclaims: “In the morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the Bhagvat-Geeta, since whose composition years of the gods have elapsed, and in comparison with which our modern world and its literature seem puny and trivial; and I doubt [wonder]if that philosophy is not to be referred to a previous state of existence, so remote is its sublimity from our conceptions.”[8]

In A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, he states, “The reading which I like best is the scriptures of the several nations, though it happens I am better acquainted with those of the Hindus, the Chinese, and the Persians, than of the Hebrews, which I have come to last.”[9]

He prefers to identify himself as a yogi rather than as a Christian mystic. In an 1849 letter, he states “Depend upon it that, rude and careless as I am, I would fain practice the yoga faithfully. To some extent, and at rare intervals, even I am a yogi.”[10]

This is also how he is viewed by his friends. “Like the pious Yogi, so long motionless whilst gazing on the sun that knotty plants encircled his neck and the cast snake-skin his loins, and the birds built their nests on his shoulders, this poet and naturalist, by equal consecration, became a part of field and forest.”[11] “His countenance had not a line upon it expressive of ambition or discontent; the affectional emotions had not fretted at it. He went about like a priest of Buddha who expects to arrive soon at the summit of a life of contemplation.”[12]

What I think most merits time devoted to this subject is the ability of Thoreau’s prose to convey the feel and import of his momentary meditation experiences:

If with closed ears and eyes I consult consciousness for a moment, immediately are all walls and barriers dissipated, earth rolls from under me, and I float . . . in the midst of an unknown and infinite sea, or else heave and swell like a vast ocean of thought, without rock or headland, where are all riddles solved, all straight lines making there their two ends to meet, eternity and space gambolling familiarly through my depths. I am from the beginning, knowing no end, no aim. No sun illumines me, for I dissolve all lesser lights in my own intenser and steadier light. I am a restful kernel in the magazine of the universe.[13]

In my better hours I am conscious of the influx of a serene and unquestionable wisdom. . . . What is that other kind of life to which I am thus continually allured? which alone I love?‚. . . Are our serene moments . . . simply a transient realization of what might be the whole tenor of our lives? To be calm, to be serene! There is the calmness of the lake when there is not a breath of wind. . . . So it is with us. Sometimes we are clarified and calmed healthily, as we never were before in our lives, not by an opiate, but by some unconscious obedience to the all-just laws, so that we become like a still lake of purest crystal and without an effort our depths are revealed to ourselves. All the world goes by us and is reflected in our deeps. Such clarity![14]

In all these accounts, Buddhism is not clearly differentiated from Hinduism or Confucianism or Sufism. Like Emerson, Thoreau mines all Oriental philosophers for what appeals to him. His imprecision about lineages, traditions and doctrines is attributable not only to limited knowledge. He does not take religion as a source of identity or a dogmatic faith. “Every sacred book,” he says, “successively, has been accepted in the faith that it was to be the final resting-place of the sojourning soul; but after all it was but a caravansary which supplied refreshment to the traveler, and directed him farther on his way to Ispahan or Baghdat.”[15]

Instead of specific historical doctrines, Thoreau affirms only what he finds to have contemporary and universal relevance, what Aldous Huxley called, the Perennial Philosophy. “There is an orientalism in the most restless pioneer,” he writes, “and the farthest west is but the farthest east.” ¦. “In every man’s brain is the Sanskrit¦The Vedas and their Agamas are not so ancient as serene contemplation. Why will we be imposed on by antiquity? And do we but live in the present?”[16]

Thoreau acknowledges his preference for Buddha, but also expresses a grudging respect for Christianity: “I know that some will have hard thoughts of me, when they hear their Christ named beside my Buddha, yet I am sure that I am willing they should love their Christ more than my Buddha, for the love is the main thing.”[17]

And though he seems to associate meditative practice with Eastern philosophy, Thoreau might well have made more references to his forerunners in the Western contemplative tradition, including for example Andrew Marvell, whose 17th century British poem, “The Garden,” celebrates a pastoral of solitude much like Walden’s.

Fair Quiet, have I found thee here,

And Innocence, thy sister dear!

Mistaken long, I sought you then

In busy companies of men :

Your sacred plants, if here below,

Only among the plants will grow ;

Society is all but rude,

To this delicious solitude. ¦What wondrous life is this I lead!

Ripe apples drop about my head ;

The luscious clusters of the vine

Upon my mouth do crush their wine ;

The nectarine and curious peach

Into my hands themselves do reach ;

Stumbling on melons as I pass,

Insnared with flowers, I fall on grass. ¦Meanwhile the mind, from pleasure less,

Withdraws into its happiness :

The mind, that ocean where each kind

Does straight its own resemblance find ;

Yet it creates, transcending these,

Far other worlds, and other seas ;

Annihilating all that’s made

To a green thought in a green shade.[18]

The composition of Walden is like a mosaic. Thoreau assembled it out of the vast collection of journal entries he kept over the two years he lived by the pond, and he revised the arrangement in several later editions. Ironically, this history of reworking strengthens the language’s immediacy. The whole book is ordered by the sequence of the seasons, but its overall temporal structure seems less complete than its constituent parts–each chapter, each paragraph, each sentence. Like haikus’ and koans’, their meaning is often hidden in puzzle and paradox that the reader must solve. I’d like us to look together at a few passages to get a sense of how the author’s voice is always heard in the present moment and is most present in intervening silences.

From Chapter 4, “Sounds”

I did not read books the first summer; I hoed beans.

Nay, I often did better than this. There were times when I could not afford to sacrifice the bloom of the present moment to any work, whether of the head or hands.

I love a broad margin to my life.

Sometimes, in a summer morning, having taken my accustomed bath, I sat in my sunny doorway from sunrise till noon, rapt in a revery, amidst the pines and hickories and sumachs, in undisturbed solitude and stillness, while the birds sang around or flitted noiseless through the house, until by the sun falling in at my west window, or the noise of some traveller’s wagon on the distant highway, I was reminded of the lapse of time. ¦

I realized what the Orientals mean by contemplation and the forsaking of works.

This was sheer idleness to my fellow-townsmen, no doubt; but if the birds and flowers had tried me by their standard, I should not have been found wanting.

I kept neither dog, cat, cow, pig, nor hens, so that you would have said there was a deficiency of domestic sounds; neither the churn, nor the spinning-wheel, nor even the singing of the kettle, nor the hissing of the urn, nor children crying, to comfort one. An old-fashioned man would have lost his senses or died of ennui before this. Not even rats in the wall, for they were starved out, or rather were never baited in”only squirrels on the roof and under the floor, a whip-poor-will on the ridge-pole, a blue jay screaming beneath the window, a hare or woodchuck under the house, a screech owl or a cat owl behind it, a flock of wild geese or a laughing loon on the pond, and a fox to bark in the night. Not even a lark or an oriole, those mild plantation birds, ever visited my clearing. No cockerels to crow nor hens to cackle in the yard. No yard! but unfenced nature reaching up to your very sills. A young forest growing up under your meadows, and wild sumachs and blackberry vines breaking through into your cellar; sturdy pitch pines rubbing and creaking against the shingles for want of room, their roots reaching quite under the house. Instead of a scuttle or a blind blown off in the gale”a pine tree snapped off or torn up by the roots behind your house for fuel. Instead of no path to the front-yard gate in the Great Snow”no gate”no front-yard”and no path to the civilized world. [19]

From Chapter 5, “Solitude”

THIS IS A delicious evening, when the whole body is one sense, and imbibes delight through every pore. I go and come with a strange liberty in Nature, a part of herself.

As I walk along the stony shore of the pond in my shirt-sleeves, though it is cool as well as cloudy and windy, and I see nothing special to attract me, all the elements are unusually congenial to me.

The bullfrogs trump to usher in the night, and the note of the whip-poor-will is borne on the rippling wind from over the water. Sympathy with the fluttering alder and poplar leaves almost takes away my breath; yet, like the lake, my serenity is rippled but not ruffled.

I have never felt lonesome, or in the least oppressed by a sense of solitude, but once, and that was a few weeks after I came to the woods, when, for an hour, I doubted if the near neighborhood of man was not essential to a serene and healthy life. To be alone was something unpleasant. But I was at the same time conscious of a slight insanity in my mood, and seemed to foresee my recovery.

In the midst of a gentle rain while these thoughts prevailed, I was suddenly sensible of such sweet and beneficent society in Nature, in the very pattering of the drops, and in every sound and sight around my house, an infinite and unaccountable friendliness all at once like an atmosphere sustaining me, as made the fancied advantages of human neighborhood insignificant, and I have never thought of them since. Every little pine needle expanded and swelled with sympathy and befriended me. I was so distinctly made aware of the presence of something kindred to me, even in scenes which we are accustomed to call wild and dreary, and also that the nearest of blood to me and humanest was not a person nor a villager, that I thought no place could ever be strange to me again.

Nearest to all things is that power which fashions their being. Next to us the grandest laws are continually being executed. Next to us is not the workman whom we have hired, with whom we love so well to talk, but the workman whose work we are.

With thinking we may be beside ourselves in a sane sense.

By a conscious effort of the mind we can stand aloof from actions and their consequences; and all things, good and bad, go by us like a torrent. We are not wholly involved in Nature. I may be either the driftwood in the stream, or Indra in the sky looking down on it.[20]

One wonders whether in passages like these the “rain of law” in The Lotus Sutra gave life to Thoreau’s imagery and thought.

In Chapter 2 of Walden entitled “Where I lived, what I lived for,” Thoreau writes of one of his favorite subjects, the morning.

Morning is when I am awake and there is a dawn in me. ¦ There [is] something cosmical about it; a standing advertisement, till forbidden, of the everlasting vigor and fertility of the world. The morning, which is the most memorable season of the day, is the awakening hour. Then there is least somnolence in us; and for an hour, at least, some part of us awakes which slumbers all the rest of the day and night¦. The Vedas say, “All intelligences awake with the morning.”[21]

This passage recalls some of my favorite songs of the 1960’s, The Beatles’ “Here Comes the Sun,” Cat Stevens’ “Morning has Broken,” Bob Dylan’s “New Morning.”

It also brings to mind an occurrence that took place a week ago last Thursday when I hiked with my 11 year old grandson and a friend of his to the top of Poly Mountain to spend the night under the stars. The morning sun bursting over Cuesta Ridge awakened me in my sleeping bag and illuminated the cloud cover below.

As I looked down over the shrouded city something thrilling arose that I didn’t know what to make of.

After a few minutes it was surrounded by something else.

My shouts finally aroused the boys.

Together we watched the phenomenon blossom and then fade.

Later in the day I searched for some explanation of this event and learned that it was known as a “glory.”[22]

In China, they call it “Buddha light.”[23]

[7] http://books.google.com/books?id=VnsAAAAAYAAJ For one discussion of Thoreau’s uses of the Sutra’s concept of “law,” see “Becoming the “Transparent Eye-Ball”: Ecodarma in American Transcendentalist Writing,” by R. Swarnalatha in Essays in Ecocriticism, edited by Nirmal Selvamony Nirmaldasan and Rayson K. Alex, New Delhi 2007, accessible at http://books.google.com/books?id=z-tEW8gU-wsC&pg=PA121&lpg=PA121&dq=thoreau+and+%22law%22+lotus+sutra&source=bl&ots=ElpUN64pT_&sig=hqLVmPhvAHJ0oLQRm7JQCQvcPd4&hl=en&sa=X&ei=kFnIUfvdCKqZyQHn-YGYCQ&ved=0CHAQ6AEwCQ#v=onepage&q=thoreau%20and%20%22law%22%20lotus%20sutra&f=false

[12] http://www.ralphmag.org/thoreau-swansJ.htmlŽ See also And Joshua Caldwell in the New Englander and Yale Review of 1891: “Apropos of his intense and defiant individualism, it is strange that his biographers and critics have paid so little attention to his profession and practice of Buddhism. ¦ it is possible to trace a vein of Buddhism all through his life and writings.” TEN VOLUMES OF THOREAU By JOSHUA W. CALDWELL, Knoxville, Tenn. 1891 NEW ENGLANDER AND YALE REVIEW. 1891. VOLUME XIX, NEW SERIES. VOLUME LV, COMPLETE SERIES. NEW HAVEN: WILLIAM L. KINGSLEY, PROPRIETOR. ARTICLE V. http://thoreau.eserver.org/tenvolumes.html

[13]http://www.walden.org/documents/file/Library/Thoreau/writings/Writings1906/07Journal01/Chapter2.pdf [pp. 53-4]

[17] text.lib.virginia.edu/etcbin/toccer-new2?id=ThoWeek.sgm&images=images/modeng&data=/texts/english/modeng/parsed&tag=public&part=all [p.55]

[21] http://thoreau.eserver.org/walden02.html

[22] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glory_%28optical_phenomenon%29

[23]http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:E1YNbAntwFsJ:www.theepochtimes.com/n2/science/buddhas-light-shines-near-chongqing-57908.html+&cd=8&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us&client=firefox-a

July 7th, 2017 at 2:56 pm

Much obliged to the author for a delightful recollection of Thoreau’s experience of Bodhi nature in living at Walden and through his writing and reading then and subsequent to it. Delightful lively story of the authors life as well , I must say! Thanks to my son , a summa cum lauded scholar now closely reading and delighting in Walden and living himself alone in a cabin in the woods in southern Indiana. Bravo to all!