My Story by Louise Marx

My earliest recollection seems to be when I was three years old sitting on my potty on the floor and the earth shook. It was a Sunday morning and there were several members of our family in our apartment in Stuttgart, Seestrasse 65. It increased my vocabulary by the word, “Erdbeben,” earthquake. That late in life, at age 80, I would live in earthquake country, California, nobody could foresee.

My next memory is of when my father returned from the office with a bulletin distributed on the streets. It was August 2, 1914, the beginning of World War I. There existed no other news media, except for the newspapers delivered a few hours later, going into detail of the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria in Sarajevo. Many of my friends’ fathers were conscripted for military service at the front. My father was in uniform but not recruited to serve in the trenches, as his health was not good enough. He suffered from asthma and bronchial conditions. He was employed by a large company which manufactured “Schiesbaumwolle,” used in shooting the cannons on the front.

next memory is of when my father returned from the office with a bulletin distributed on the streets. It was August 2, 1914, the beginning of World War I. There existed no other news media, except for the newspapers delivered a few hours later, going into detail of the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria in Sarajevo. Many of my friends’ fathers were conscripted for military service at the front. My father was in uniform but not recruited to serve in the trenches, as his health was not good enough. He suffered from asthma and bronchial conditions. He was employed by a large company which manufactured “Schiesbaumwolle,” used in shooting the cannons on the front.

As the war continued, we had to prepare for aircraft attacks every night by putting warm clothing on a chair next to our beds and toys to take down to the cellar where we spent many evenings. Anti-aircraft was close to our section in Stuttgart. As soon as one heard the siren one was supposed to enter the nearest house for shelter. At home we went to the cellar. Father had a wine cabinet down there and took the key along to open a bottle for the grownups. Children got apples which were also stored downstairs. For us kids it was lots of fun.

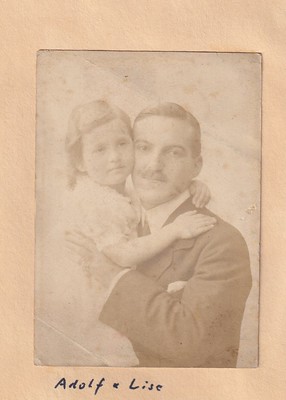

Adolf went toboganning with me, we took long walks, and sang together. The Stuttgart zoo was not far from where we lived. On one of our visits, I came close to the monkey cage. I had two pigtails with rust-colored satin bows, and before I knew it, a monkey had grabbed a bow and disappeared with it. Another day my father asked me what I would prefer, either ride a donkey in the zoo or attend a concert in town. My answer was, “on the donkey to the concert.”

Adolf went toboganning with me, we took long walks, and sang together. The Stuttgart zoo was not far from where we lived. On one of our visits, I came close to the monkey cage. I had two pigtails with rust-colored satin bows, and before I knew it, a monkey had grabbed a bow and disappeared with it. Another day my father asked me what I would prefer, either ride a donkey in the zoo or attend a concert in town. My answer was, “on the donkey to the concert.”

On Easter my parents would hide eggs and presents, mostly outdoors in the beautiful woods surrounding Stuttgart. During the summers the family would go to the Black Forest, where we would celebrate their wedding anniversary. I picked flowers for them and told the hotel staff so they could arrange for a special cake.

I had problems with telling the truth. Once I came home from school and told everyone I had seen a large herd of sheep on the way. I repeated it and mentioned a friend of my father having walked along with me. So Adolf called him and found out that it was all a fabrication. I was carefully watched by my parents and every time I came up with some fib, I was punished. I also was punished for things I didn’t do. We had an elegant salon and one day a chinese vase was broken, but noone believed me when I told the truth, that I was not involved. I had stolen a five-mark bill out of my mother’s purse and hidden it in a music book.  One day during practise when she sat next to me on the bench, the bill fell out. She took me to her psychologist-physician and told him about my problems. After a serious talk with him, I stopped lying for good.

One day during practise when she sat next to me on the bench, the bill fell out. She took me to her psychologist-physician and told him about my problems. After a serious talk with him, I stopped lying for good.

My father was interested in high fashion. He inisted that I speak proper German and not our local Swabian dialect. His wardrobe was made by the most expensive tailor in Stuttgart. When he was called for fittings, he took me along. There was no ready-made clothing at all. My own dresses were made by a seamstress who came to the house, or for special occasions by an expensive ladies’ dress shop.

Every year around Christmas I was invited to go to the theatre. I saw Cinderella and Hansel and Gretel and I still have the playbills.

I spent most of the years between four and seven with my Danish governess, Leni Erhardt. Denmark was a neutral country so she had no problem working for a German family. At age seven, 1917, I entered a private school accompanied on the first day by my mother. The Rothertche Maedchenrealschule was a rather exclusive place and only girls whose parents were in good financial circumstances could afford it. The first three years we still lived at the Seestrasse apartment, but then moved to the Hauptmansreute, which was higher up in the hills. I had a longer walk to school, but lived in a better neighborhood.

As the war continued, my father had to give up one of our five rooms at this new apartment to another man who had no place to live. He was a nice man from the civil service who did not bother us at all. My governess was no longer needed. She went back to Denmark, but we stayed in contact with her for many years. We had one domestic who cleaned and cooked and she slept in a small room under the roof which was hot in summer and freezing in winter. Of course no heat or running water, no bathroom. Her sheets were red-checked rather than white. A bell from our floor was connected to the maid’s room in case she overslept. Breakfast had to be served at 7:30 before my father went to work.

The owner of the apartment house was Karl Eitel. He was a garden architect and had four children who began to introduce me to the facts of life. Herr Eitel beat up his wife and she ran screaming out in the street, but they stayed together as long as we lived there. The photos in my album, starting with me in 1911 to 1917, show our summer vacation in the Black Forest I remember my father travelling a great deal. When he returned for the weekend he took me on a Saturday morning to the office of the firm and I was introduced to the various partners and office personnel. There were no typewriters. Letters were hand written and then put into a copy press on blotter paper and forwarded to the recipient. Mail was delivered twice a day and the mailman rang the bell when there was mail in the mailbox.

I was a frail and slender child, suffering constantly from digestive problems. I was not allowed to eat fresh fruit and spent a great deal of time in bed. I was sent to a mineral spa in Bad Kreuznach run by a retired army officer and this seemed to alleviate the problems. Nourishment during the war was turnips, little meat and no butter, unless one bought provisions from the peasants on the black market. I remember going by train with my mother to the small town of Memmingen where our maid had relatives. We collected some eggs and butter and brought them home hidden under our clothing. On Saturday nights my father came home from the barracks and brought along good black bread which only the soldiers could get. I still remember my mother’s smile when he arrived home. The school assigned us to collect acorns and beechnuts in the woods. The acorns were used for coffee, the beechnuts for oil. It was part of our class work.

Friday afternoons my mother walked with me to Cannstatt, where her parents lived, and we prepared for the Shabbat ceremony. Grandmother and Grandfather were active in the synagogue. She belonged to Chevra Kadisha, preparing the remains of members of the congregation for their burials, washing and clothing them before the funeral. I remember sitting in the Sukkah erected in their back yard. Grandfather was a board member of the synagogue. Although they observed the High Holy Days, I don’t remember ever celebrating Hannukah. On their fiftieth wedding anniversary they were awarded with a medal brought by the king’s emissary. Shortly thereafter my grandmother died. Grandfather lived a few years longer and often visited us.

I got religious instruction from Hebrew teachers while other students in school studied their religions. The instructors were paid by the state, and everybody had to pay church tax. This gave the city records of everyone’s religion. Although he had been Bar Mitzvahed, my father never observed any holiday. We celebrated Christmas but with no tree, only a large wreath on the gift table. The maids received presents, cookies they baked themselves and one orange each, and on this occasion we all assembled together in the living room and sang carols. The traditional Christmas eve meal was goose, which I liked better than anything else we ate all year.

There was always music in the home. My mother Thilde took voice lessons and played the piano. My father sang Shubert songs with her. Opera was at its height and we always had a yearly subscription with the best seats available. During the intermission one could buy ham sandwiches. Everybody was dressed elegantly. My cousin Else, eight years older than I, studied voice and planned to become an opera singer. On Christmas under her direction we performed one act of Hansel and Gretel, by Humperdink, Lotte, Else’s sister, playing Hansel and I playing Gretel. The whole family attended at Uncle Karl’s music room. Alfred Grau, a cousin of Else and Lotte, played the violin.

Karl and his wife Ella provided me with a second home. Often I was allowed to sleep over on weekends sharing beds and stories with my cousins. A few years later, Else tried to convince my father that I had a nice soprano voice and that I should study for the theatre. He didn’t agree and told her not to influence me in that direction. After her first engagement in Saarbrueken’s opera house, when Else came back to Stuttgart and told us about her adventures and love affairs, my father sent me out to the kitchen to get a glass of water, and he told me to let it run a long time to make it nice and cold. We were one of the first owners of a gramophone. It was presented to my father by a client from China, Mr. Si, who frequently negotiated deals in cotton fibres, an area in which my father was expert. Adolf had been living in China and Japan from 1904 to 1907, long before I was born.

At last, in November 1918, the war was over, the German army defeated by the Allies. The treaty of Versailles was signed. After Kaiser Wilhelm II escaped to Dorn in Holland, Germany become the Weimar Republic. The sum of reparation left Germany unable to pay and started a huge inflation of the currency.

My most traumatic experience up to this day at age 84, took place on September 5, 1919, the day before my birthday. A number of my friends had been invited for the party on September 6. My father could not be home because was in Berlin on a business trip. As I often did, I knocked at my mother’s bedroom to get into her bed before getting up. There was no reply and opening the door I discovered she was not in her bed. Next to the bedroom was our bathroom. I tried to open the door but it was locked from the inside. Next to the bathroom was our porch with a frosted glass window. I climbed on a chair and through the window I saw the outline of a body in the bathtub. It was my mother Thilde. The water in the tub was heated by a large gas oven. I do not know if it was shut off or not. I ran out to call the maid. She ran down to get the owner Mr. Eitel. How the door was opened I have no memory. I only know that shortly afterwards I sent a telegram to my father in Berlin: “Hotel Excelsior, Berlin. Come back. Mutti had an accident.” In the living room presents for my birthday were spread out on the table. Somebody called the children not to come to the party. I think I was staying at my Uncle Karl’s overnight, and my father picked me up on his return by train, ten hours from Berlin to Stuttgart. I remember my mother lying on her bed and father taking me in to see her. She looked beautiful. The day of the funeral I was with relatives.

The fact that there was a large family from both sides, with aunts, uncles and cousins, helped me over the first few months of the tragedy. I was taken to Saarbrueken, where two of my father’s sisters lived. They had a large dry goods store, in which I hung around and watched. It also was the year of the revolution after the end of World War I, and Saarbrueken was occupied by French Moroccan soldiers, a black regiment. My relatives lived right in the center of town, both families in the same building. One of my aunts, Tante Anna, had lost her husband in the first year of the war. I never met him. But their daughter Lise, nine years older than I, became a good friend and was like a sister. Her mother was the bookkeeper in the dry-goods store. She was hard of hearing and poor. My father invited them to come to Stuttgart to stay with us and keep house while he was often away on business. Lise, age 18, found a job in Stuttgart as an office help and her mother kept house. Father moved into the small room which I had and we three slept in the master bedroom in two beds.

It was not the best time for a ten year old girl. My father advertised for a housekeeper to take care of me and him, but none of the replies were satisfactory. I became ill with pneumonia and was not allowed to get out of bed for eight weeks. There were no antibiotics available, but complete bedrest and good nourishment were prescribed. Our physician came to the house once a week to check my lungs. No X rays were ever taken. I read a great deal and felt miserable, since few visitors were allowed.

My father was travelling during the week and came home on weekends. One day I received two beautiful books by mail from a lady in Leipzig by the name of Paula. She wrote a loving letter to me. She had met my father at a relative’s house in Leipzig and fallen in love with him. Adolf had told her about his ten-year old daughter, Lise, sick in bed, and from then on I received many gifts, books, letters and the most beautiful dress I had ever seen, made by her for me. It fitted perfectly.

Father and Paula Friedeberg got married in Leipzig in a big hotel with many friends and relatives who travelled by train to attend the wedding. Rabbi Goldman performed the ceremony. I was one of the flower girls. By then I was fully recovered from the long illness. There were many skits performed by members of both families. But when the moment came for the newlyweds to leave for their honeymoon, I cried and insisted I wanted to go with them. But I had to return to Stuttgart with the other family members.

Lise and her mother moved out of the apartment and took over my grandfather, Adolf’s father’s apartment. My grandfather who was deaf and 85 years old, committed suicide by jumping out of a window while my parents were on their honeymoon.

My father was the youngest of the eight children of Joseph Gruenwald. I never met his wife Louise, after whom I was named. She died of cancer years before I was born. In May 1921 I had a new mother, only fourteen years older than I was. She insisted I that I not use the word “stepmother,” and that I call her “Mutti,” as I had called my real mother Tilde. A few months after their wedding I was told that I could expect a brother or sister, and being an only child, I felt very happy that there would be a baby in the family.

My father was the youngest of the eight children of Joseph Gruenwald. I never met his wife Louise, after whom I was named. She died of cancer years before I was born. In May 1921 I had a new mother, only fourteen years older than I was. She insisted I that I not use the word “stepmother,” and that I call her “Mutti,” as I had called my real mother Tilde. A few months after their wedding I was told that I could expect a brother or sister, and being an only child, I felt very happy that there would be a baby in the family.

Those years were relatively happy ones. Father had a well paid position in a firm with branches all over the world. He travelled a great deal and once in while he took his young wife along, while I stayed with the baby, Hannelore and the nurse. I was always welcomed at my Uncle Karl’s family, the parents of Else and Lotte, who at that time also lived in an apartment.

On the third floor of our apartment house lived two ladies, refugees from the Russian Revolution in 1917. They were highly educated, and one of them gave piano lessons. She was my first piano teacher. One day somebody played upstairs and I could not hear it. Adolf was greatly concerned, knowing that there were two people deaf in our family, his father and his sister, Anna Bloom. We travelled to Tuebingen, a university, where a famous ear-nose and throat specialist was practising. After examining me and taking hearing tests, he discovered that I had otosclorosis which might get worse with age. It is an inherited disease usually jumping one generation. Neither Adolf nor Tilde were affected. The prognosis was “wait and see, but no pregnancy in later life.” But at that time I didn’t worry. I had no trouble in school since I was always the shortest girl in class and had a front-row seat.

On the third floor of our apartment house lived two ladies, refugees from the Russian Revolution in 1917. They were highly educated, and one of them gave piano lessons. She was my first piano teacher. One day somebody played upstairs and I could not hear it. Adolf was greatly concerned, knowing that there were two people deaf in our family, his father and his sister, Anna Bloom. We travelled to Tuebingen, a university, where a famous ear-nose and throat specialist was practising. After examining me and taking hearing tests, he discovered that I had otosclorosis which might get worse with age. It is an inherited disease usually jumping one generation. Neither Adolf nor Tilde were affected. The prognosis was “wait and see, but no pregnancy in later life.” But at that time I didn’t worry. I had no trouble in school since I was always the shortest girl in class and had a front-row seat.

At age thirteen I had whooping cough. I suffered a great deal because I was expected to suppress the coughing. My parents had gone to Switzerland, and I was taken to the Black Forest to speed recovery by Aunt Sophie, Alice’s mother. Since I was no longer contagious, Alice could be together with us in Freudenstatt. Sophie habitually told Alice how much better I was and how much more she liked me. This caused problems between us cousins and made ours a love-hate relationship for many years. Later on, when we both attended a commercial high school, things between us improved. Sophie’s marriage to Hugo, Alice’s father, was a tragedy to the very end, when he died in an insane asylum in Winnenden.

The inflation was tremendous for about three years and I remember Adolf calling Paula to spend everything she had as household money because tomorrow it would be worth nothing. Once the German mark was stabilized, one billion became one mark

After things began to get normal, the wish to live in one’s own house–“Villa” in Germany–became the goal of the upper middle class. My parents bought a plot of land on the other side of town and hired two architects to build a one-family house with a garden and a small swimming pool for the children. At that time another baby was on the way, Gabi, and more space was needed. I had my own room on the top floor with warm and cold running water, built-in bookshelves, writing desk and my bed. I enjoyed the privacy. When I wanted to take a bath I had to go to my parents’ bedroom on the second floor.

After things began to get normal, the wish to live in one’s own house–“Villa” in Germany–became the goal of the upper middle class. My parents bought a plot of land on the other side of town and hired two architects to build a one-family house with a garden and a small swimming pool for the children. At that time another baby was on the way, Gabi, and more space was needed. I had my own room on the top floor with warm and cold running water, built-in bookshelves, writing desk and my bed. I enjoyed the privacy. When I wanted to take a bath I had to go to my parents’ bedroom on the second floor.

My schooling took many turns. I started with private school for about six years. During the inflation I went to public school where I made my lasting friendships, and the last year I went back to graduate from the private school. There was no coeducation all the way to the university. For half a year, at age fourteen, I spent a wonderful time in a boarding school in Agnetendorf, close to the border of Czsechkoslovakia. We often saw Gerhard Hauptman, the famous writer, author of Die Weber, walking around town. The school was run by three elderly sisters, Hoeniger, who were Jewish, but it was a non-sectarian school attended by many young people, male and female, from Germany, Poland and France who had problems at home. Henry and I visited the place in 1936, when Hitler already had started the Third Reich. We found the old ladies still alive, but the school was no longer in existence. We did not feel comfortable in this part of Germany since many of the citizens wore the swastika button and one felt the impending change.

I spent my summer vacation in Muehringen, at a camp sponsored by the B’nai Brith, which Adolf belonged to. It was a new experience for a person from a non-observant home. I enjoyed going to synagogue on Friday, praying before and after the meal and learning the rituals. Back home I felt uncomfortable with a cold meal, or pork chops and no candles, but my parents did not change their way of life for me.

My own life after Agnetendorf began to change. Boys became visible. I dated a few Jewish boys in Stuttgart, but never fell in love until I was 16.  It was Kurt Schloss, age 18, who lived close by. He had problems with a father who suffered from depression and had to spend every autumn at a sanatorium. Kurt was managing the business of bristles and brushes, and he had great responsibility at such a young age. He also had lost his mother and had a stepmother. We found many things in common. We played tennis every Sunday from four to eight. My father talked to me about the relationship, explaining that it would be in my interest to get more involved with other boys and not continue to see him exclusively, as it would cost us more heartbreak the more we were together. For quite a few months, we met in secret. Then, like many young men in good financial circumstances, he spent six months in Paris, to learn French and to get to know women. I suffered a great deal during those months, but in the end I followed my father’s advice and dated other young men. Nobody would have imagined that we all meet again in the USA married and fortunate to have escaped the fate of millions of our contemporaries. Kurt married Maya, my friend Elsbeth’s younger sister. They moved to Los Angeles, where he managed the Laemmle movie theatres, owned by another Stuttgart family, and later studied to become a very successful CPA. He died at an early age of emphesyma and left a young widow and a small boy behind.

It was Kurt Schloss, age 18, who lived close by. He had problems with a father who suffered from depression and had to spend every autumn at a sanatorium. Kurt was managing the business of bristles and brushes, and he had great responsibility at such a young age. He also had lost his mother and had a stepmother. We found many things in common. We played tennis every Sunday from four to eight. My father talked to me about the relationship, explaining that it would be in my interest to get more involved with other boys and not continue to see him exclusively, as it would cost us more heartbreak the more we were together. For quite a few months, we met in secret. Then, like many young men in good financial circumstances, he spent six months in Paris, to learn French and to get to know women. I suffered a great deal during those months, but in the end I followed my father’s advice and dated other young men. Nobody would have imagined that we all meet again in the USA married and fortunate to have escaped the fate of millions of our contemporaries. Kurt married Maya, my friend Elsbeth’s younger sister. They moved to Los Angeles, where he managed the Laemmle movie theatres, owned by another Stuttgart family, and later studied to become a very successful CPA. He died at an early age of emphesyma and left a young widow and a small boy behind.

During one winter vacation my friend Lotte Tiefenthal and I planned to spend some time in Berwan, Tirol, a small ski resort high up in the mountains. It could only be reached by sled, and the hotel picked us up at the railway statin. We had settled in, when after three days I developed a high fever, so we called our parents Lotte’s father had a large car and chauffeur and my parents equipped it with bedding. I was brought down to the car by sled and transferred into the car and driven back to Stuttgart on a long, strenuous ride. I was taken to the Marienhospital and put into quarantine. It turned out I had the measles and no visitors were allowed. At the little window of the door I saw a young man with a bunch of violets waving at me. It was Heiner Marx.

During my seventeenth year, I took one year of home economics and learned cooking, baby care and kindergarten. I made new friends, and looking over the photo album of that period reminds me that I had a good life. The summer vacation in 1927 was spent in a small town near Lausanne in order to improve my French. It was a coed boarding school with young people from all over Europe. We were under strict supervision of “Madame,” and although I was fond of a boy from St. Gallen, we shared no more than an occasional kiss. We were taken to the Chateau de Chillon, where Lord Byron wrote his poetry and we took boat trips on Lake Geneva. My friend Vera from Budapest, with whom I continued to correspond since our days at Agnetendorf three years before, joined me during the summer in Switzerland with two Hungarian friends.

It was now time, after my graduation from school and from finishing school, to decide what next. I would have like to attend a class for gymnastic and dance for which I felt qualified. There was a school run by a Jewish woman who trained girls for this profession. It was rather expensive, but my father, aside from the tuition, disapproved of its reputation. I remember how disappointed I was since I always liked to dance in ballet performances at the clubs to which my parents belonged. It was suggested I register at the Commercial High School, which took two years to graduate with a good chance to find a secretarial position. Besides typing and shorthand we studied fourteen different subjects, including English, French and Spanish business correspondance, bookkeeping, economy, composition, math. My cousin Alice also attended.

During the last year of school, I was called to the phone in the principal’s office. Paula had given birth to a much-wanted boy. I was eighteen years old when Hans Peter was born, the only male who continued the name Gruenwald. I was a bit embarrassed to return to the classroom and give the news to my friends. A big family celebration was held after the circumcision, although Paula was still in the hospital. I had to play the hostess and champaigne was poured, the first I ever drank.  A few months later, my parents gave me a house party as a debutante. We must have been 25 people, boys and girls. Somebody played harmonica. It took place in the garden and the large garage. Beer was served. Paula had a talent for arranging such gatherings. Occasionally she went into the house and nursed Hans Peter.

A few months later, my parents gave me a house party as a debutante. We must have been 25 people, boys and girls. Somebody played harmonica. It took place in the garden and the large garage. Beer was served. Paula had a talent for arranging such gatherings. Occasionally she went into the house and nursed Hans Peter.

The year was 1928 and we still lived under the Weimar Republic. It was also the year I was allowed to vote the first time. We had 24 parties from left to right. I voted social democratic while my parents voted democratic.

It also was the year I took a vacation before I started my first job and joined Heiner Marx and Hans Weil, a second cousin of mine, to go skiing to Obergurgl in Austria. It was April and the sun in the Alps was ideal for skiing. I had never skied in such high altitude and terrain. Henry and Hans found a small hotel and I found a roommate by the name of Alice Eberhart from Munich. She was an experienced skier and somewhat older and we made a lasting friendship. When we unpacked our suitcases in the hotel I took out my warm flannel pyjamas while she took out an elegant sheer nightgown saying, “One never can tell.” When the two boys left us for two days to do an Alpine tour, they were snowed in and couldn’t return as planned because they were stranded by a snowstorm in an emergency shelter. But we couldn’t worry about them and had a great time together. After three days they returned. Resting in the sun the next day, Henry and I held hands under a blanket.

Coming home, I started work on my first job in a bookshop in the bookkeeping and consignment department and waiting on customers. The pay was minimal considering the long hours, so I checked the newspaper and found a help-wanted ad for a foreign language secretary fluent in English, French and Spanish. I applied, bringing several dictionaries with me in my briefcase, took the test given by the boss, who fortunately knew no other languages, and got the position. It paid twice as much as the bookstore. We had a two hour lunch break and sometimes my father would drop me off with his firm’s chauffeured Mercedes Benz. My company had two departments. One was vacuum cleaner repair, the other was manufacture of tin cans and metal signs. I worked mostly for one man who dictated in German while I translated into the appropriate language.

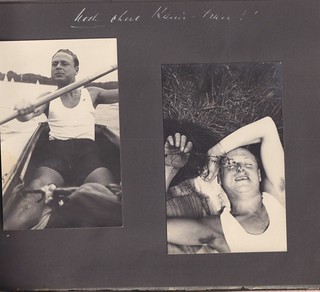

Henry went back to his job as manager of Tiefenthal and Halle, a fine lingerie store. He was in love with Lotte, the daughter of the owner, and she was a good friend of mine. She confided in me that she decided on another man, much older and well to do, and while they were breaking up, he came to me for comfort. We got closer and began to spend Sundays making trips in our foldboat on the beautiful small rivers around Stuttgart.  We canoed in summer and skied in winter, took the train at 6:00 a.m. to reach our goal and returned in the evening.

We canoed in summer and skied in winter, took the train at 6:00 a.m. to reach our goal and returned in the evening.

The romantic part began when I was eighteen, at Fasching or Carnival. People came in costume and masks and danced at many balls. I was dressed as an American Indian with feathers around my waist and a headdress. Henry was dressed as the Pied Piper of Hamlin and we danced most of the night, went home to change and took the 6:00 a.m. train to the Black Forest for skiing. I remember that on the three hour train ride we talked about our problems with our parents.

In 1931 Henry left for Berlin because his firm was faltering from too much expansion. He wanted to get away from his home town, his parents, and from Lotte, his former girl. He got a job in large shoe store, Salamander. After months of daily correspondance we decided to meet for a weekend in Meiningen, a pretty town halfway between Stuttgart and Berlin. The meeting was arranged for Yom Kippur 1932. I visited his mother Elise, to tell her of our rendezvous. She showed no signs of shock. Henry’s train arrived about the same time as mine. We had a reservation in the best hotel in town, two separate rooms connected with an inside door. We spent two wonderful days, walking the town, going to the theatre and we decided to marry. But I still did not lose my virginity. We knew that the time had not yet come, since we lived in different cities.

We would have to support ourselves without parental help. I was hoping to get a job in Berlin and talked to my father about our plan. Paula and Adolf liked and trusted Henry from the moment they met. My father remembered a schoolmate who was the chairman of Berlin’s electric company. He wrote to ask for an office job for his daughter. Within a few days a positive reply arrived. I could start as of March 1933. I gave notice at my job in Canstatt, packed a big trunk and had it shipped to Berlin. I met Dr. Kaufman for a few minutes to thank him for the prompt arrangement of my new job at a salary of RM 180 monthly which made it possible to pay for my room and board. I was part of the typing pool MeanwhileAdolf Hitler was elected Chancellor on January 3, 1933,

Henry found a furnished room for me about fifteen minutes from where he lived, since I had promised my father not to move in with him. In the evenings we would meet for a cold supper and discuss the day’s events.  It was romantic but somewhat fearful due to the political atmosphere. We lived in a part of Berlin where artists, writers and left wing intellectuals congregated. We subscribed to left-wing magazines, played records of left wing composers on our portable record player that we took with us boating.

It was romantic but somewhat fearful due to the political atmosphere. We lived in a part of Berlin where artists, writers and left wing intellectuals congregated. We subscribed to left-wing magazines, played records of left wing composers on our portable record player that we took with us boating.

Henry was promised the position of manager of a large shoestore, but on April 1 1933 the dream ended. The brown shirts entered the electric company with a list of all Jewish employees, including Dr. Kaufman, to tell us we had lost our jobs. They said that the company was “gleichgeschaltet,” which meant that as a public employer, it could keep no Jewish workers. I received three months’ severance pay, which gave me a chance to look for other work. Henry sensed what might happen with Salamander and accepted a job with a Jewish firm in ladies’ neckwear. Most of this industry was in Jewish hands. I found temporary employment with Jewish firms. I had to move seven times because landlords didn’t want Jewish people and didn’t like frequent visitors.

I was asked to fill a temporary vacancy at a music publishing house, Allegro Verlag, owned by Ernst and Ellen Goodman. They were distant relatives of Paula, who visited with them when she came to see me. The Nazis left private enterprises alone, as it was in the interest of the German economy. Allegro was involved in the production of an operetta named “Die Lodernde Flamme–The Blazing Flame.” The libretto was written by a non-Jew, Mr. Kuenneke, and he would come to the office to discuss changes in the script and the music. Whenever he arrived, Ernst Goodman put on his iron cross from World War I thinking it would protect him from persecution. My name was changed from Fraulein Gruenwald to Gruener to sound less Jewish. I had to come to the theatre during rehearsals to record changes in the text and to set out the scores for the instruments. This taught me about the trials and tribulations of staging a performance. After the debut, which received lukewarm reviews, my job was finished. Later, I learned that Ernst and Ellen had perished in the Holocaust.

I returned home to Stuttgart to announce my engagement with a big family party. Two months later, June 3 1934, we were married by Rabbi Rieger in a small room of the Stuttgart synagogue with only a dozen close relatives present. My father gave a meaningful speech which I still have in a box with letters and documents including a speech of my grandfather at Adolf’s wedding in 1909. My cousin Else Seyfert, who was an operatic mezzo-soprano, was supposed to sing at our wedding, but she came down with a migraine attack and had to cancel. Henry prepared the itinerary for our honeymoon trip, which he paid for. The first night was Zurich followed by a train trip to Palanzo on Lago Maggiore, Milano, Ortisay in the Dolomites and Venice. There we were welcomed by swastika flags marking the meeting of Hitler and Mussolini taking place at the time. It was great to come home to our Berlin apartment on Hohenzollerndam which Henry had rented from a Jewish couple who had left for Paris.

Arriving by taxi at our place, we had no money left to pay the driver, but my mother Paula, who had travelled from Stuttgart to Berlin, surprised us by planting flowers on our patio and filling the icebox with goodies. She bailed us out and paid for the cab. It was July l934. We knew that eventually we would need our own furniture, and with Adolf’s assurance that he would pay for whatever we bought, we gave the job to an interior decorator who designed the livingroom,breakfront, table, chairs, and couch plus bedroom set and kitchen. Everything was delivered on schedule and the owners of the rented furniture had it forwarded to Paris. It was a beautiful, elegant place. With money from some of our friends and father’s firm, we bought a fullsize carpet for the living room and a Blaupunkt radio and record player, the best there was.

In the back of our minds we knew that someday we may have to leave and emigrate to another part of the world. America was still not in our thought. We figured maybe Holland or England. Henry travelled frequently to the Netherlands to sell to the big department stores. I was left alone in our apartment and was busy assorting a large stamp collection which Henry had inherited from a distant relative. A friend of ours taught me how to do it. In June 1935, when every morning the storm troopers marched along our building singing the Horst Wessel Song, we began to contact relatives in the U.S. to ask for an affidavit. The quota was still high, but my father’s oldest brother, Hugo, a pianist and piano teacher in New York, refused to give it because he had pledged for Lotte and Else, my cousins. Hugo’s son-in-law, Sam Leidesdorf, was a wealthy accountant, married to my cousin Elsa. Sam was a well known public figure nominated for mayor of New York, but we could not depend on him. Julius, the younger brother of Adolf, lived in St Louis, where he was married to Frieda, my mother Thilde’s older sister. But though she also worked as a salesperson in a department store, they could not afford to sponsor us.

After all these efforts to get the affidavit failed, one day we were contacted in Berlin by Gustav Rosenfelder, an American citizen living in Danbury Connecticut, where he had a men’s felt hat factory. He took us out to a fancy restaurant and told us he would sponsor us in case we wanted to come to the U.S. He ended up sponsoring about fifty other people not related to him. They all owed their lives to this man. He was called “crazy,” maybe because of his goodness, but he stuck to his word, and after our arrival in New York, we met him a few times. Years later he committed sucide by jumping out of the window of his apartment. He had a charming wife from Romania, two natural children and an adopted son who had polio, for whom he built a special ramp to get by wheelchair into his house in Connecticut.

Mr. Albert Cohen, Henry’s boss, had moved to London and left the running of the business to him in Berlin. Cohen asked Henry to go to his apartment in Berlin to pick up important documents and bring them over the border. Henry risked his life to deliver them He had been promised that if things got too hot we could move to London and he could become a partner or employee. We both travelled to London to discuss the situation, visiting Cohen in his beautiful home in Wimbledon. He said the time was not ripe yet. After that we no longer trusted him. On our return to Berlin via Amsterdam we found a forwarded letter with Gustav’s affidavit from America.

Returning home, Henry gave notice to Mr. Cohen and we prepared for immigration. You needed a visa from the consul, but we had learned that the consul in Berlin was an SOB, just like the one in the opera by Menotti. My father knew the consul in Stuttgart personally. We had to take up residence there for two months to receive the visa, helped by a box of Havana cigars for the consul from Adolf. We had to spend all our money in Germany, so we fitted ourselves out with all the clothing we could buy. Our belongings were packed under the supervision of a Nazi officer, placed in a lift van and shipped to New York, all paid for in D marks. Whatever money was left we gave to Elise. It was a difficult goodbye to her and all our friends and family.

Returning home, Henry gave notice to Mr. Cohen and we prepared for immigration. You needed a visa from the consul, but we had learned that the consul in Berlin was an SOB, just like the one in the opera by Menotti. My father knew the consul in Stuttgart personally. We had to take up residence there for two months to receive the visa, helped by a box of Havana cigars for the consul from Adolf. We had to spend all our money in Germany, so we fitted ourselves out with all the clothing we could buy. Our belongings were packed under the supervision of a Nazi officer, placed in a lift van and shipped to New York, all paid for in D marks. Whatever money was left we gave to Elise. It was a difficult goodbye to her and all our friends and family.

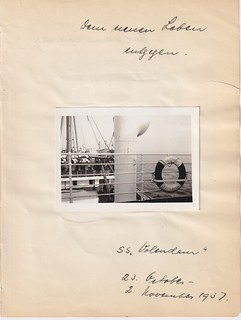

On October 23, we took the train to Amsterdam and boarded the S.S. Volendam, travelling first class to spend the last of our German money.  Before our embarkation we visited with our friend Lotte Meyer and her husband in Amsterdam and we envied them for living in peaceful Holland. Lotte’s sister and her husband, Lisbeth and Henry Worms, had been living in Amsterdam for years. He had a good position in a bank. But they had left for the U.S. before us, seeing the handwriting on the wall. A few years later, the Meyers and their young son were forced from their home. They lived hidden in someone’s house, like Ann Frank’s family, and later they fled to the woods. Their young son was raised by a Catholic family and joined them after the war, when they at last could emigrate to the U.S. sponsored by their sister and brother-in-law.

Before our embarkation we visited with our friend Lotte Meyer and her husband in Amsterdam and we envied them for living in peaceful Holland. Lotte’s sister and her husband, Lisbeth and Henry Worms, had been living in Amsterdam for years. He had a good position in a bank. But they had left for the U.S. before us, seeing the handwriting on the wall. A few years later, the Meyers and their young son were forced from their home. They lived hidden in someone’s house, like Ann Frank’s family, and later they fled to the woods. Their young son was raised by a Catholic family and joined them after the war, when they at last could emigrate to the U.S. sponsored by their sister and brother-in-law.

Our ocean voyage was interesting except for my being seasick most of the time. We were received by relatives and friends who travelled to Hoboken, New Jersey at 8:00 A.M. on November 2, 1937. Passport check and immigration presented no problem. Our papers were in order. Somebody had rented us a furnished room on 110 St. and Broadway in Manhattan, where we shared the kitchen with other tenants. Our English was sufficient for conversation with the American family. After I had gotten over a bad sore throat and fever during the first week, we looked for an apartment. The fact that we had the amount of 1600 dollars with a non-Jewish friend in Sweden gave us a cushion in case Henry could not find a job. It was still the end of the depression and Roosevelt had just begun to get the country out of its worst slump. We started walking up Broadway from 110 St. to 200 St. looking for a reasonable place to live. Our lift van had been stored until we were ready to have it delivered.

Our papers were in order. Somebody had rented us a furnished room on 110 St. and Broadway in Manhattan, where we shared the kitchen with other tenants. Our English was sufficient for conversation with the American family. After I had gotten over a bad sore throat and fever during the first week, we looked for an apartment. The fact that we had the amount of 1600 dollars with a non-Jewish friend in Sweden gave us a cushion in case Henry could not find a job. It was still the end of the depression and Roosevelt had just begun to get the country out of its worst slump. We started walking up Broadway from 110 St. to 200 St. looking for a reasonable place to live. Our lift van had been stored until we were ready to have it delivered.

We ended up at 1781 Riverside Drive, opposite beautiful Fort Tryon Park and the Cloisters. We moved into our one bedroom apartment with elevator and attendant for 52 dollars a month. We used the living room for our bedroom, sleeping on two couches to be changed to beds at night. The second room we rented out to a woman from Stuttgart. This reduced our rent to 26 dollars per month. We were settled in our apartment on the fourth floor and warmly received by the neighbors because we spoke English. Henry contacted a couple from Berlin who manufactured hand-sewn ladies’ gloves, which were in style. They hired him as a salesman at fifteen dollars per week. After several weeks he contacted Liberty Lace and Manufacturing company, the firm he had worked for on his previous visit to New York in 1925. Mr. Metzger, the senior partner, hired him to work in the plant and sell lace to the dress manufacturers. At 18 dollars per week, it was a considerable improvement in our income.

In the summer of 1938, we received a letter from Elise, Henry’s mother. She was told by a German Christian lawyer to leave Germany as soon as possible, due to a planned “aktion” by Hitler against the Jews. Since we were closely related we were able to send her the affidavit and she received the visa in Stuttgart. She arrived on the New Amsterdam ten months after we had started our new life. Elise was close to 60 when she arrived.  Her English was non-existent, but she was experienced in sewing and running a home. With some misgivings, we asked Mrs. L. to leave and took Elise in. We ended up all suffering under the situation. Elise always offered well meant but unnecessary help, since I was no newcomer to housekeeping. We had very little privacy even though we moved to a two bedroom apartment in the same building.

Her English was non-existent, but she was experienced in sewing and running a home. With some misgivings, we asked Mrs. L. to leave and took Elise in. We ended up all suffering under the situation. Elise always offered well meant but unnecessary help, since I was no newcomer to housekeeping. We had very little privacy even though we moved to a two bedroom apartment in the same building.

I started working in a textile firm. But my hearing was not good enough to hear the numbers called out from one room to another. After four weeks I was fired and I felt miserable. I was tested at the League for the Hard of Hearing, and they lent me a hearing aid. This helped me perform in a new job as a chairside dental assistant for Fred Rothenberg on Arden St. At only $7.50 per week I mixed fillings, assisted at extractions and also had to clean the office, fix lunch for the boss and type the bills. But the office was in walking distance from home.

I had seen people selling novelties in private homes. One day Elise brought home a gimmick called “Spring Apron,” which was on wire that snapped around your waist. I bought it for 25 cents wholesale and sold it for 75 cents. It sold like hotcakes, so I added more items and made good money. I went to the apartments in our buildings around Christmas and I was allowed to show them in hospitals to patients and nurses. I had appointments on Park Ave. and was always politely recieved. I must confess that I never paid income tax.

I was aware that all this was not a permanent solution. Many of the women I knew became masseuses. In order to do so, one needed a license which required passing a difficult exam. I studied with a German physician who could not practise because of his lack of English. He taught in German but most of the terminology was Latin. The exam didn’t cover practise but it was on medical concerns. One question: “Describe how to do a colon massage.” Another: “What parts of the body should one not massage?” The examination room was filled with former MD’s who couldn’t get the license to practise medicine. We were not allowed to massage men unless they had a physician’s prescription.

After having passed the massage examination I had very little practical experience. I received my first practical training at Melquist, Fifth Ave. where I was paid $18.00 per week plus tips. I was required to give about 18 massages per day, each lasting 40 minutes, ladies only. The women came out of the steam bath and were wrapped into sheets lying on the table. Tips were between 25 and 50 cents. After several weeks I felt ready for better paying jobs and landed at “The Fountain of Youth” in the Bronx, working half a day only and making better money. For this type of work I did not have to wear my hearing-aid, as the women were either relaxing and not talking, or close to my ears. Coming home in my white uniform,which I had to supply, I emptied my pockets of tips. Often they amounted to $5.00.

Then I felt secure enough to try on my own and give private massages. My first client was the manager of the Bank of Manhattan. I showed my license as an ID at the bank and he asked for an appointment. He came to my apartment on Riverside Drive. He weighed 200 pounds and I had to move all the furniture to set up the table. He undressed in the bathroom but left his underpants on. In the other room I had stationed my cousin Hansi, “just in case.” He loved the massage and acted like a gentleman. He came for a few weeks. I liked the money and told Hansi I didn’t need her any more. One day he got fresh and I told him not to come back. The professional “massage” entailed many meanings. I had to be careful not to respond to ads in the NY Times. Once I applied for a job on 7th Ave. and was asked to go out in the evening to a hotel. Of course I declined the offer.

After being married for seven years, I was very eager to have a child. But the warning of the German physician who had advised against pregnancy had always been our guide. I had even had abortion during the fourth month done by a German gynecologist, and on the cab ride home with Henry I had tried to put the matter behind me.  We applied for adoption but our income and living conditions were not sufficient. Then a doctor friend, Kurt Landsberg, advised us to see an American specialist regarding my hearing problem. We met Doctor Woodrow in Yonkers and told him our story. He disagreed with the diagnosis and was furious about the unnecessary abortion. He strongly advised me to go ahead and conceive. The next month, October 1941, I was pregnant.

We applied for adoption but our income and living conditions were not sufficient. Then a doctor friend, Kurt Landsberg, advised us to see an American specialist regarding my hearing problem. We met Doctor Woodrow in Yonkers and told him our story. He disagreed with the diagnosis and was furious about the unnecessary abortion. He strongly advised me to go ahead and conceive. The next month, October 1941, I was pregnant.

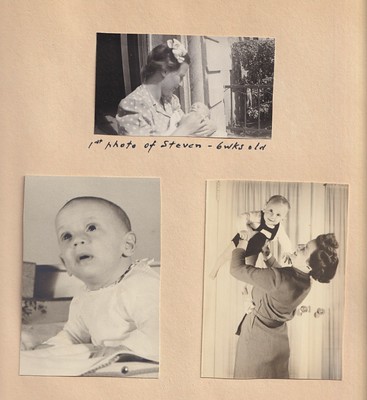

With the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. entered the war in December 1941. Henry was drafted and passed the physical at Grand Central station. Although he was 34 years old, he was declared 1A. Only the fact that I was pregnant in my fifth month allowed him to be deferred. He enlisted for war work in a munitions factory at fifty cents per hour and worked 60 hours a week. It was quite a contrast to Liberty Lace. On July 13, Steven was born after a difficult sixteen hour delivery. It was the hottest day of the year and there was no air conditioning.

Twelve days later, we brought the baby home still a bit yellow from the jaundice he had at birth. We notified Dr. Woodrow who was overseas in the army. He sent us a wonderful letter. We had a crib, carriage, sterilizer, everything handed down from friends, and we received many presents. Elise was busy knitting little jumpsuits for her grandson. Living close to Fort Tryon Park, we took him out morning and afternoon. He was bottle fed, as I had no milk for breast feeding.

Twelve days later, we brought the baby home still a bit yellow from the jaundice he had at birth. We notified Dr. Woodrow who was overseas in the army. He sent us a wonderful letter. We had a crib, carriage, sterilizer, everything handed down from friends, and we received many presents. Elise was busy knitting little jumpsuits for her grandson. Living close to Fort Tryon Park, we took him out morning and afternoon. He was bottle fed, as I had no milk for breast feeding.

Elise was our built-in babysitter for the first two years, but the moment had come to separate. Three generations in one apartment was just too much. I suggested we stay in our beautiful building, but Henry could not agree to move his mother out and take a stranger in. So we moved to a one bedroom apartment on Arden St., a less pleasant location. Steven slept in our bedroom and was a restless baby, knocking his head on his bedboard, waking us and the neighbor who thought it was us. It was an agonizing time.  We thought we would live there temporarily, but we were stuck until 1950, as no apartments were available.

We thought we would live there temporarily, but we were stuck until 1950, as no apartments were available.

Elise found a furnished room where she had to share a bedroom. For three months Elise cut us off, not speaking to us or answering our letters. Finally, Martha Landman played the conciliator. Elise moved to 1815 Riverside Drive, where Mrs. Goldsmith had a nice room while her husband was in the army overseas. Elise was busy in her alteration business, going out all day and earning income of her own.

During the war, German Jewish immigrants sponsored the purchase of a bomber called the “Loyalty Plane,” which was launched at La Guardia airport where we all attended the ceremony. We went to services on the high holidays and joined a very orthodox Congregation headed by Rabbi Neuhaus. Most of our friends also joined. Henry became chairman of the Inwood section of the United Jewish Appeal. In 1948, when the state of Israel was born, I joined Hadassah, a woman’s Zionist organization supporting the new state.

The winters in New York were cold, the summers hot and humid. The blizzard of 1947 gave us the opportunity to use our skis, which we brought from Germany. We went to Macy’s and bought Steven a complete ski outfit and went skiing in Fort Tryon or Inwood Park,  and on weekends to Bear Mountain, where a ski tow was installed to pull you up the mountain. One winter we planned to spend Christmas and New Years in Pine Hill in the Catskills. Steven and I took the easy slope while Henry took the expert run. Over the loudspeakers we heard the announcement, “Mrs. Marx, come to the emergency.” There was Henry with a broken leg, slightly in shock. I had never driven in ice and snow, but we put Henry in the back seat while Steven next to me was wheezing with an asthma attack, and I drove to the hospital in Margaretville. After taking X-rays they put on a heavy cast and sent Henry to our hotel on crutches. The hotel gave him a room on the ground floor. In the morning we heard a knock on the door. He had come upstairs on his crutches. We stayed for one more day and then decided to return to New York. The highway was cleared and we ended up celebrating New Year’s Eve at home. The cast was on for six weeks, but he never missed a day of work.

and on weekends to Bear Mountain, where a ski tow was installed to pull you up the mountain. One winter we planned to spend Christmas and New Years in Pine Hill in the Catskills. Steven and I took the easy slope while Henry took the expert run. Over the loudspeakers we heard the announcement, “Mrs. Marx, come to the emergency.” There was Henry with a broken leg, slightly in shock. I had never driven in ice and snow, but we put Henry in the back seat while Steven next to me was wheezing with an asthma attack, and I drove to the hospital in Margaretville. After taking X-rays they put on a heavy cast and sent Henry to our hotel on crutches. The hotel gave him a room on the ground floor. In the morning we heard a knock on the door. He had come upstairs on his crutches. We stayed for one more day and then decided to return to New York. The highway was cleared and we ended up celebrating New Year’s Eve at home. The cast was on for six weeks, but he never missed a day of work.

My parents visited in New York and were quite shocked at our living circumstances and Adolf invited me to come to Brazil for a visit to Sao Paulo where he and his family had emigrated in 1939. I left Steven with Henry and Elise and took the thirteen day cruise on the Moore McCormack line to Santos, the harbor of Sao Paulo. I had a great time. The Korean war had just begun. Henry was so glad to have me back that he brought me a diamond ring when he picked me up at the pier.

In 1950 we were able to afford a better place to live. We found a larger apartment in Riverdale, a new upscale neighborhood. A new development, not quite finished, went up and we rented a 2-bedroom apartment on the 4th floor of the 6-story building. At last we had a bedroom for ourselves and Steven had a room of his own. There was no road and landscaping finished, no phone line established. After we moved, Elise took over our place on Arden Street and shared it with a roommate.

In 1950 we were able to afford a better place to live. We found a larger apartment in Riverdale, a new upscale neighborhood. A new development, not quite finished, went up and we rented a 2-bedroom apartment on the 4th floor of the 6-story building. At last we had a bedroom for ourselves and Steven had a room of his own. There was no road and landscaping finished, no phone line established. After we moved, Elise took over our place on Arden Street and shared it with a roommate.

Steven had attended first and second grade at PS 152 in Inwood. He liked the sclool, was a good reader and rather advanced for his age. In Riverdale he started third grade at PS 81 on Riverdale Ave. There he was bored, and I went to the principal, Mrs.Simpson, and asked for a transfer to another class, as there were various levels. My request was denied with the remark that I had a problem, but “that public school was not for the bright child.”

Shortly after moving, I developed my private massage business. I bought an aluminum folding table, which I could transport in the car. I had gotten my driving license on the first test. I started out with one of the women in our building who had diabetes and needed the massage for medical reasons. She recommended me to all her bridge friends. Ninety percent were Jewish and with all of them I developed personal friendships. I worked in the morning or early afternoon before Steven’s return from school. He never had a latch key or came into an empty house. When I had a few customers in the evening, Henry was at home. I earned nice money, not a fortune, but it gave me the satisfaction to contribute something to the household.

I joined the troup of mothers in Netherland Gardens who became Den Mothers for the Cub Scouts. Each group had about 6 boys working on projects which could be done in the house or outdoors. One of my boys was David Botstein, today a well-known scientist at Stanford University. I also started a new group of Hadassah in Riverdale by inviting a group of 20 women to our apartment and asked the chairperson of the Bronx chapter, Charlotte Jacobsen, to speak. At the end of the meeting we had 20 new members and called it the Fieldston group of Hadassah.

By then Elise was happy in her apartment on Arden Street. Her alteration business had increased, though she never took work home. She took the subway to Long Island and was beloved by all her customers. Her name was “Omi Marx.” Came Christmas, she was asked to bake Christmas cookies for Mr. Laufkoetter of the Metropolitan Opera. Else Seyfert hired her for baking and sewing. She was self supporting. Every Friday evening we were at her place for dinner. There was often a Linzer Torte to take home. Nothing was ever too much for her.

Once in Riverdale, we joined a liberal congregation where Steven was not happy. When the Conservative Synagogue was founded we became members. Steven wanted a more thorough Jewish education and preparation for his Bar Mitzvah. He became president of the Youth Group. Rabbi Kadushin became a personal friend although he knew we had little religious background.

After four years at P.S. 81, Steven went to Junior High down the hill for two years which counted for three and entered DeWitt Clinton High School at age 17. It was an all-boys high school. When the weather was bad, I drove him to school to spare him from taking two buses. His teachers were impressed by his intelligence and reading level. Dr. Bernhardt, his advisor, suggested that he try for Columbia. City College was free, but we felt we could afford the tuition, $1200.- per year, and a small NY State scholarship of $250.- per year. We attended his graduation from De Witt Clinton and had dinner at the Riverdale Inn.

That summer Steven and his friend Weisskopf spent two weeks hitchhiking around New England. In those days the young people went in search of adventure and although we didn’t like it we let them do their own thing. At the end of the summer, Columbia started and together we all decided that he should live at home for one year at least. We just had fitted out his room with white carpeting, hi-fi, and bookshelves.  The second half of his second year, he decided to live in a room in a residence hotel near the campus. As he packed his belongings, I cried in my bedroom behind a closed door because I felt this was the end of our close relationship. When we visited his new place, a rattrap for which he paid an unreasonable amount, we realized we had to let him choose his own life. In order to support himself he tutored, as we did not provide for his living expenses. I guess all mothers feel that way when children leave home, and even though I had to let go, since he lived in town, we saw each other regularly when he came home for a good meal.

The second half of his second year, he decided to live in a room in a residence hotel near the campus. As he packed his belongings, I cried in my bedroom behind a closed door because I felt this was the end of our close relationship. When we visited his new place, a rattrap for which he paid an unreasonable amount, we realized we had to let him choose his own life. In order to support himself he tutored, as we did not provide for his living expenses. I guess all mothers feel that way when children leave home, and even though I had to let go, since he lived in town, we saw each other regularly when he came home for a good meal.

In the fifties, Dr. Rosen, a famous otolaryngologist, had done research in China and returned with a new type of surgery. I was one of his first patients in New York. After two days in the hospital I was released and able to put away my hearing aid. The idea of the surgery was breaking a bone in the middle ear to open the closed passage. But after about two years the cartilage grew together and I went back to the hearing aid. Nevertheless I always followed up new medical developments. One day Dr. Woodrow passed me on the sidewalk in Yonkers. He stopped his car and called to me, “See Dr. Sheer in Manhattan.” I found his phone number in the directory. He was the first specialist who performed “mobilization of the stapes” surgery. The idea was to insert a plastic tube to keep the ear canal open. After the surgery I spent two nights in the clinic and then went home and could hear the crickets chirping and Henry’s snoring. When I went back for a checkup he told me I was one of the few who had complete success. Today it is an accepted surgery and the plastic is replaced with platinum. Many years later when I was on Medicare, I decided to have the second ear done in Colorado. It was again a complete success. The surgeon there performed fifteen operations on the same day.

With my improvement in hearing I could function again taking dictation, because I had taught myself to change my German shorthand to English. I discontinued massage and went back to my old profession of secretary. I usually worked part-time to leave room for household duties. In the morning I was at Rabbi Carlebach, an ultra-orthodox rabbi, the father of the famous Shlomo. In the afternoon I was the assistant of Dr. Rothchild, an orthopedic surgeon, who also wore a hearing aid. He trained me to take X-rays, develop them, and give physical therapy. Once he went to Hong Kong and left me in charge of his office. He paid two dollars per hour. After two years I asked for a raise. He claimed he could not afford it, so I left.

Then I began to work in a big office on Fifth Ave. for an agency dealing with restitution from the German government. People with knowledge of German and English were very much in demand. I also worked for the Jewish Agency, assisting a writer named Kurt Grossman who was working on a book entitled “The Unsung Heros.” One of the main topics was the Schindler story, which recently has become famous as a result of the Steven Spielberg film. Mr. Grossman dictated directly as I typed or I took shorthand for correspondance with well-known members of the German Republic like Willy Brandt, first mayor of West Berlin and later Chancellor of Germany.

This assignment was followed by work for restitution of German-Jewish institutions in cities and towns destroyed by the Nazis. A short time I worked for our attorney and friend Helmut Kramer as a legal secretary. His untimely death interrupted a brilliant career. For a few months I helped out at William F. Mayer Co., Henry’s employer. It was not a good situation, since Henry was there as an executive while I was on the clerical staff. I also worked for two years at Macy’s as a typist-secretary shortly before my 60th birthday, partly in the typing pool and partly in the foreign department and in the Telex room. With my discount card I could buy anything from clothing to food, eat at the cafeteria and get full benefits.

Our financial situation began to allow trips abroad. In 1964 we went back to Europe for the first time. We were met by our cousins Marta Stiel and Lise Frank who showed us around Paris. The first Friday we went with relatives of Elise to the Conservative Synagogue where the women and men were separated and the ushers wore uniforms. Afterwards the family took us home for dinner. Saying goodbye to my cousins I fell and tore a ligament. Upon arrival in Rome I went to the American hospital, got bandaged and continued sightseeing. But at the hotel I discovered Henry had left my clothes in the closet in Paris, so I bought a beautiful brown linen suit on the Via Veneta and wore it all through our travels. Half a year later the clothes arrived by mail in Riverdale.

In 1968, shortly after the six-day war, we visited Israel. We were so impressed by the land and its people that we toyed with the idea of emigrating to Jerusalem. The fact that we didn’t speak the language and a warning from friends who were leaving Israel to come to the U.S. made us change our minds.

In the late sixties our income allowed me to do more volunteer work. A tennis friend, Carolyn Sapir, who lived in Fieldston told me about “school volunteer training.” We had to attend the course and were assigned to an all black school in Harlem. She drove and we parked in a garage near the school. We taught simple math and reading on a one-to-one basis. The principal was Jewish and knew every student by name and they all loved her. This work gave me great satisfaction. I often shared my lunch with children who came to school without breakfast. I taught second and third grade with great success. One student stands out in my memory. His name was “McThaddeus.” He was nine years old, motivated to learn. One day his mother came to the teacher and asked, “Who is Mrs. Marx?” In his dreams at night he was constantly calling her. We took boys and girls to Bear Mountain on a Sunday roasting hotdogs and marshmallows. While I was tutoring in Harlem, the first Black Bank opened on 125 St. I decided to invest some of my savings. Here I was the minority, the only white person to stand in line, as I wanted to show my support for African Americans.

The veterans hospital in the Bronx appealed for volunteers to help with paraplegics who had no visitors–some from World War I and some from World War II. I was assigned to a quadruplegic who needed to be fed. I also made conversations with him. He was a man in his thirties, very fond of me. After a few weeks, they changed me to another patient, explaining it was not good for him to become too attached. I also worked with an armless man who painted with a paint brush in his mouth and did astonishing work. One evening around Christmas, Henry and I were sent to the psychiatric ward to entertain the mental patients, and we took small presents. There was a band and we danced with some of the inmates. I also helped with clerical work in the VA office. As a volunteer at Montefiore hospital I assisted in the first pacemaker surgery. At Polyclinic Hospital, I learned physical therapy from Professor Kovac and applied it to the patients.

When Elise was 86, at one of our Friday evening meals at her house, we noticed that her speech was blurred. When I asked if I should stay with her, she insisted we go home. The next morning when we called, there was no answer. We opened the apartment and found her lying on the couch unable to speak. Dr. Myer her physician confirmed our diagnosis that she had suffered a stroke. We wanted her transferred to the Jewish Memorial hospital, ten minutes away, but he said they wouldn’t accept long term patients and suggested a nursing home. She was taken to one recommended by a friend. Not only was it a firetrap but in an impossible location and little attention was given to her.

A week later we had her transferred to the Sawmill River Nursing home in Yonkers which had large grounds and was conveniently located. The fact that Dr. Meyer failed to admit her to the hospital forced us to finance the Nursing Home for which Medicare wouldn’t pay. We paid what seemed like a fortune–ninety dollars per week–until the last year when Medicaid covered the cost.

Elise shared the room with a lady who was deaf and fortunately could not hear her constant crying. She was well taken care of and never suffered bedsores. She could eat with her left hand which was not paralyzed. The staff was attentive and appreciated our frequent visits and gifts. When the weather was good we took her outside in her wheelchair to see the trees and have fresh air and sunshine. On my days off I brought her a little apple pie which she loved to eat. We had a one-way conversation but she signalled that she understood although she couldn’t speak. I remember when Steven and Jan visited her for the first time after returning to New York from California. Steven was wearing a wrinkled shirt. She tried to smooth the wrinkles, looked at Jan and shook her head.

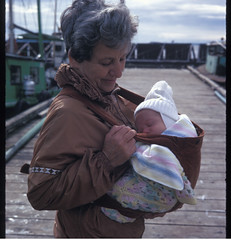

On December 12, 1970, after six long years of illness, she fell asleep for the last time at 92 years of age. It was a freezing December morning when the funeral service at the Riverside Chapel was held, and despite the short notice, a large crowd showed up and drove out to the gravesite at Cedar Park Cemetery in Bergen County New Jersey. The access to the grave was a sheet of ice. When we called Steven to tell him of Elise’s death, he told us that on the same day, he and Jan, who was pregnant for the first time, had bought a hundred-year old farm in Powell River, British Columbia.

Since most public tennis courts in Riverdale were free of charge, I took up tennis which I played in Germany. I had access to the courts of the the Horace Mann and Fieldston schools. I was in demand as a partner and there I met Cora Weiss, founder of Women’s Strike for Peace. Along with other women there I joined various anti-war organizations including SANE. During the Vienam war Henry and I joined Women’s Strike for Peace on a protest march to Washington. On our return to the train we were maced by officers of the Justice Department and coughed all the way back to New York.

Henry joined the Reform Democratic club and attended its meetings regularly. During one Thursday evening’s meeting in the Bronx, Martin Luther King was assassinated. I heard it on the radio at home at 9:00 p.m. I called the club where our Congressman, Jonathan Bingham, was the speaker. They had not heard the news and immediately closed the meeting and returned home. It was dangerous to be out since rioting and burning was expected in that neighborhood.

After several years of volunteering, I decided to return to gainful employment. I got a job in the office of Skyview on Hudson, five minutes from home. I had to write the leases and collect the rent, check the vacancies and check the condition of the apartments when tenants moved in and out. I could use the beautiful swimming pool across the street and went home for lunch. The building had twenty five stories and was the most luxurious one in Riverdale. Many tenants failed to pay their rent and we had to evict them. I learned a great deal about real-estate law, checking with the downtown office regarding sublets and missing payments. I stayed for two years and for some reason one of the supervisors didn’t like me and let me go. I applied for unemployment compensation and received it after lengthy negotiations.

In 1970 we went to visit Strasbourg, the city where Henry was born and lived till he was four. We stayed at the Hotel de la Paix. Returning there one day after a walk in the park, we heard the word “Israel” on TV, but couldn’t understand the full story in French. The receptionist said, “Madame on n’a pas des mots.” It was the massacre of the Olympic athletes in Munich. The date was September 5, the anniversary of my mother’s death. We were planning to celebrate my birthday in Metz the next day with the Stiel family.

My last paying job was assistant to the editor at the Leo Baeck Institute, an archive and research facility for German Jewish history. I met many interesting and famous people, like Peter Gay, who had changed his name from Froelich, at their yearly memorial lecture. It was a shock for Mrs. Muehsam, the editor of Newsletter, my boss, when I told her I had to resign because my husband had retired and wanted to leave New York.

We were no longer tied down by Elise and the fact that we were robbed in an elevator one Saturday night made the decision easier. Our plan was to travel and see the world and maybe live in Switzerland for a while to follow our friends Kurt and Eva Easton who had moved to Lucerne. But after spending three months in Switzerland and discovering the difficulty of getting residence status, we returned to Riverdale. At that time my school friend Hilde Milstein was regularly coming to New York to buy merchandise for her store in Denver. She knew we loved the mountains and skiing. She said, “Why not try Colorado?”

We decided to give it a go, but for me it was extremely hard to leave New York. When the movers appeared, I left, because I couldn’t face the packing. Henry had promised we’d stay for one year, and if I wasn’t happy we would return. At the end of April 1972, we prepared to leave for Denver. We planned to travel in our new Plymouth, the first car we had to buy in a long time, since Henry’s firm had provided him with a car. On our last day in New York, we drove downtown to say goodbye to our friends Lisbet and Henry Worms. We parked in a space that said “free on holidays,” since it was a Jewish half-holiday. When we returned to the car, we found it was towed away to some place near the Hudson River. We were desperate. All our documents were in the glove compartment. We returned to their warm apartment and called the AAA but it was too late. Finally we found out where the car was taken, and for the sum of $175.– they released it. The next morning we put our last belongings, including the pressure cooker, into the car and drove across the George Washington Bridge.

We spent the first night in Pennsylvania and at the restaurant where we ate dinner, people tried to convince us to settle in their town. But we continued west, at about 400 miles per day. We arrived in Denver in the middle of a snowstorm and spent our first two nights at the Milsteins’ home. Then we moved to an apartment hotel with cooking facilities at fifty dollars per week. We studied the map and looked for an apartment. Denver appeared to us like a garden city with snow mountains in the background. We found an apartment on Corona Street with two bedrooms and baths and pool for $175 per month, much less rent than in New York. Then we called the movers in New York to forward our belongings. When the moving van arrived, we checked the bill and found we’d been overcharged by hundreds of dollars. A moving company in Denver weighed the van and confirmed we were cheated. We threatened to report the mover to the ICC, and eventually he returned the excess amount.