The Message of the Trees

[Published in the Western Chapter News of the International Society of Arboriculture, March 1983]

Readers of The Western Chapter News may be interested in two remarkable tree books published in recent years but not reviewed in the trade journals. They are Trees by Andreas Feininger (New York: Penguin, 1978, $9.94) and The Tree by John Fowles and Frank Horvat (New York: Little Brown, 1980, $24.95). Large formatted and lavishly produced, both books combine stunning photographs with informative, provocative and beautifully written texts. Their authors enjoy worldwide artistic reputations: Feininger exhibits in major museums and has published numerous other photographic studies; Fowles is a best-selling British novelist, author of The French Lieutenant’s Woman; Horvat is an eminent French landscape photographer.

Though none of these artists is a tree professional, their work displays extensive knowledge; more important, it expresses the kind of lifelong respect and affection for trees that lies at the heart of the arborist’s vocation. Like truly skilled tree work itself, these books represent a labor of love, an outpouring of praise, and and application of human art inspired by the art of nature. By deepening awareness of the value and meaning of trees, the authors hope ultimately not only to enrich human experience but also to save trees and forests from the wanton destruction to which they are still subjected.

In his introduction to Trees, Feininger states that he has created

…a new kind of book not a text nor a manual

nor a tree identification book, nor still another book proving

trees are beautiful, but a tree appreciation book.

In fact both these books promote tree appreciation in similar ways. First is through simple presentation. By selecting, composing and framing each tree portrait, the photographer brings forward aesthetic qualities–qualities of strength and fragility, of symmetry and variation, of balance and tension–that normally pass unobserved. Recalling Feininger’s shot of the massive central trunk of a twisted oak in a German park, I stop my morning run to admire the gnarly Quercus agrifolia in my neighbor’s yard. Or stuck in freeway traffic, I flash on Horvat’s portrait of the Wych Elm silouetted by a January mist, and suddenly I’m greeted with the sight of an Ulmus americana arching its limbs over an Arco station.

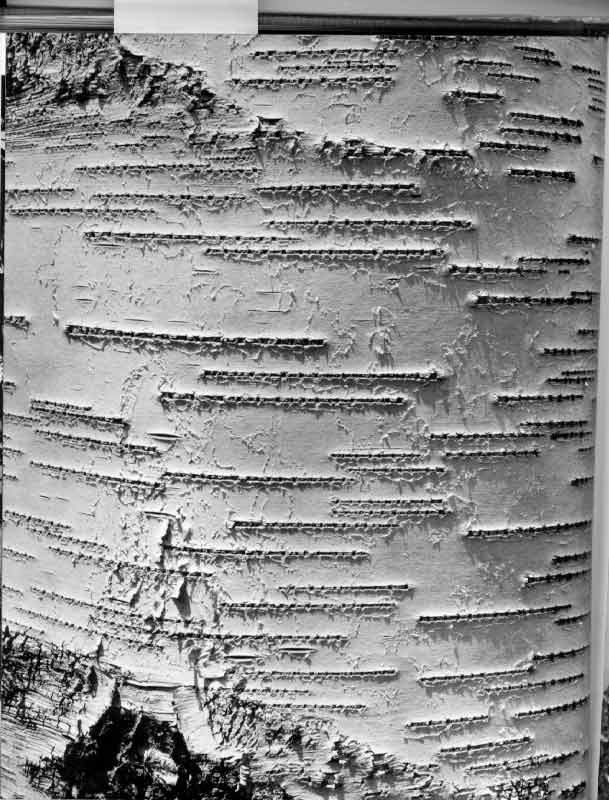

Appreciation of trees is also fostered by these books’ focus on detail. They slow and thereby enrich our perceptions of pattern, texture and light: Horvat’s row of pollarded sycamore crowns, Feininger’s mulberry leaves outlined black against the white sky, or his sweetgum leaves outlined against the dark background foliage. In such treatments of detail, the artist’s gift emerges. For while a lengthy series of photographs of bark in a tree identification book becomes schematic and dull, Feininger’s seventeen-shot sequence on trunks manages to build steadily to a dramatic visual climax. Each full-page portrait varies light, camera angle, distance, background and composition, delighting us with the variety contained in repetition.

Tree appreciation involves understanding as well as aesthetic enjoyment, and both books help to develop botanical knowledge. Horvat and Fowles identify species, location and season, while Feininger orders his pictures to illustrate explanations of taxonomy, adaptation and structure. However, the greater contribution of both books lies in their lyrical accounts of the mental, emotional and spiritual effects that trees have on people. Here, for instance, is Horvat’s description of his response to deliquescence: “…I am happy to stare at them for minutes on end, my mind blank, both relaxed and satisfied by the way the successive upward branchings have now conquered space.” Or here is Feininger on the live oak:

The shadow which a century-old live oak casts is immense and neither excessively dense nor sparse. Light and air pass freely through the interstices between the leaves and create a feeling not unlike that of being in a room the doors and windows of which are louvered to let in light and air while shutting out glare and heat. Four hundred people or three dozen cars fit comfortably in the space shaded by a single live oak.

And here is Fowles recounting his sensations upon returning to a long forgotten grove of ancient oaks in the Dartmoor barrens:

…It is the silence, the waitingness of the place, that is so haunting; a quality all woods will have on occasion, but which is overwhelming here–a drama, but of a time span humanity cannot conceive. A pastness, a presentness, a skill with tenses the writer in me knows he will never know; partly out of his own inadequacies, and partly because there are tenses human language has yet to invent.

This passage expresses the core idea of both books. Ultimately, they seek awaken our appreciation of what Feininger calls “The Spiritual Legacy of Trees.” Each in its own way ventures to interpret the obscure wisdom that trees have seemed to offer people ever since the origins of human consciousness. Both writers repeatedly mention our likely evolution from arboreal ancestry; both elaborate the central symbolism of trees in mythology, religion and poetry; both meditate on the clue to the meaning of life that trees still seem to hold:

I try to understand the message of the trees by giving my thoughts free rein. I feel great patience and tenacity, humility and acceptance of the inevitable–qualities that well benefit proud man. I think about the purpose of all life and ask myself: What is the purpose of a tree? What is the purpose of an animal? What is the purpose of man? And it occurs to me that perhaps the purpose of all living things is simply living–to play our nature-assigned role in the great drama of life; to participate, be it on ever so modest a scale, in the orderly unfolding of the cosmos….

But despite their similarities of title, format and purpose, these two books differ radically in attitude; differ in ways that are particularly interesting to the arborist. Starting with his title, Trees, Feininger emphasizes the plural. His subject is multiform, dividable, complex. He sees trees as a set of species, organs, structures, products, and stages in the ecological cycle; and his book is divided into sixteen chapters, into subchapters and into separations of text, illustration and caption. The authors of The Tree, on the other hand, are fanatics for the singular. Not only do they leave out chapters and headings, they even omit page numbers–one assumes, in order to give more a sense of indivisible, organic wholeness.

Singularity is emphasized in Horvat’s photographs. Rather than depicting “a beech” or a root formation, as would Feininger, Horvat treats the tree as a distinct individual with a unique personality–usually standing alone in a field or against the sky. And Fowles’ text attacks science itself for ignoring the individual and being “obsessed by general truths, by classifications that stop at the species.” Early in the book, he recounts his visit to the Linnaeus garden in Uppsala, Sweden. There, instead of paying tribute to the great taxonomist “who attempted to docket all of animate being,” he regards the place as the scene of the fall into forbidden knowledge. According to his line of thought, the rational process of naming, classifying and analyzing involves an illegitimate wresting of power from nature and signals the beginning of urban blight and worldwide pollution.

To Horvat and Fowles, “The Tree” as a singular is not only an individual being, but an abstract symbol–a symbol of nature as primitive, mysterious and unknowable. This ideas of nature as an energy opposed to the artificial order of civilization is rooted in the ancient philosophy of “primitivism,” popular among the Greeks, Renaissance poets, and nineteenth century Romantics. Whether musicians, poets or dramatists, primitivists traditionally put down urban commercial life and sing praises of what they call “The Green World,” which they envision at once as the wilderness, the countryside and the garden. According to this tradition, the green world symbolized by the tree also represents an inner world of the human soul–the unconscious realm whose vigor, spontaneity and fertility has been alienated by modern technological civilization. It is the role of the artist–in this case, the writer and photographer–to put us back into the green world by helping us listen to the trees:

The return to the green chaos, the deep forest and refuge of the unconscious is a nightly phenomenon and one that psychiatrists–and torturers–tell us is essential to the human mind. Without it, it disintegrates and goes mad. If I cherish trees beyond all personal (and perhaps rather peculiar) need and liking for them, it is because of this, their natural correspondence with the greener, more mysterious processes of mind–and because they also seem to me the best, most revealing messengers to us from all nature, the nearest its heart.

This primitivistic attitude accounts for some of The Tree’s peculiarities of style. In addition to abandoning chapter headings and page numbers, Fowles also leaves out any normal indications of emphasis, sequence and transition. His prose proceeds by association and image rather than by argument or analysis; to use his own comparison, reading it is like walking through a forest in which there is a choice of paths. Horvat’s photographs share this romantic character. In contrast to the clarity and precision of Feininger’s best shots, all of which are in black and white, Horvat’s color studies are muted, moody and obscure studies of tone rather than outline. While Feininger shows us vegetation, rooted in the earth, lighted by the sun, performing photosynthesis, Horvat presents brooding or exultant spirits giving off a mysterious luminosity of their own–as if he had used infrared or Kirillian photography. And while Feininger includes an appendix with technical information about lens openings, shutterspeed and ASA for each shot in his book, Horvat refuses to reveal any secrets about how he manages to achieve his astonishing painterly effects.

Since Fowles and Horvat see the tree as a symbol of “namelessness” and of “inalienable otherness,” it makes sense that they should express some misgivings about producing a book about trees made of words, photographs and, worst of all, paper. Thus, Horvat speaks of the photograph itself being parasitic upon the tree, While Fowles’ final words state the desire to hear himself stop talking:

I turned to look back, near the top of the slope. Already Wistman’s Wood was gone, sunk beneath the ground again; already no more than another memory trace, already becoming an artifact, a thing to use. And end to this, dead retting of its living leaves.

And the last photograph of The Tree pictures a Cupressus sempervirens in the middle of a foggy cemetery–the only trace of human presence Horvat has allowed in the entire book.

Less poetic, self-conscious and morbid, Feininger’s work ends with an astounding shot of a huge fractured cliff pointing upward into the wind, on top of which grow a stand of beeches, each in turn ready to be hurled into the sea below as the land is eroded away. Each of these troops is followed from behind by an endless train of tenacious replacements. The concluding feeling here is not so much one of morbid pessimism as of cautious hope. Feininger seems to be leaving us with the idea that despite the ills that both trees and flesh are heir to, some values will hang on, reproduce and continue to survive. Rather than seeing his own media of expression–and civilization itself–at war with nature, Feininger attempts to combine science, technology and art to bring us into harmony with nature. Convinced that more knowledge about trees is compatible with more feeling for trees and that an environmentalist’s outlook is a product of more rather than less civilization, Feininger ends his book with a plea for ecological action.

Where do arborists stand on the debate between primitivistic vs. civilized attitudes toward trees represented in these two books? Obviously most of us would be more inclined to side with Feininger, would find Trees more congenial than The Tree. We are not druids, or poets or back to the landers. We relate to trees as cultivators; we plan and cut and control and experiment; we keep records and get paid; we civilize nature and naturalize civilization. And yet I suspect that the extreme viewpoint of the primitivist has some appeal to anyone in this profession. For who would want to make a living climbing, who would choose to escape the environment of concrete and paper, who would be able to move with “that slower speed of plants,” unless he or she heard some invitation to come away to the green world, some silent call of the wild, some message from the trees?

Winter 1983