Why Care? An Address for Holocaust Remembrance Day

My earliest memory is of walking through Fort Tryon Park in upper Manhattan trailing an unraveled roll of toilet paper behind me. I was surrounded by a throng of ecstatic strangers shouting “Victory” at the news of Germany’s defeat. It was VE day 1945. At three years old, I didn’t know what it meant to be a Jew, but I did know enough about Nazis and Swastikas to participate fully in the festivities. The very sounds of those words, and especially of the name associated with them, “Adolph Hitler,” were as terrifying as the huffing and puffing of the big bad wolf. Like the three little pigs, we were dancing because the wolf was dead.

As I approached elementary school age, I learned more about Nazis and Jews from my parents’ explanations of what happened to the people in the photograph albums I would pore through on rainy days. A few were “deported”–whatever that meant–the rest were dispersed all over the world, or occasionally came to visit us for coffee and cake on Sunday afternoons. For some reason, they never seemed as jolly as other people’s relatives.

Going to the synagogue in the storefront next to the A and P supermarket on Sherman Avenue deepened my sense of a heritage of gloom. It was a world of old people dressed in black, with ponderous expressions, chanting exotic and mournful melodies in strange languages. They had a comforting intimacy with one another, but the togetherness always seemed like huddling. On the one hand, I felt cherished and sheltered by them, on the other alienated and repulsed.

By the time I reached grade two, I had learned some things about anti-semitism. Pictures of the survivors of Auschwitz and of the crematoria were being shown in movie newsreels. And Hitler wasn’t the only one who hated Jews. I remember Ralphie and Vinnie, my friends in our tenement apartment house, coming home after catechism and announcing with great satisfaction that my Jews had killed their Jesus. I felt some obscure connection between the concrete statue of a man wearing a crown of thorns nailed to a cross on the front of the church and the stories about torture in concentration camps, but I couldn’t make sense out it.

I also couldn’t make sense out of the fact that our relatives spoke Hitler’s German. It bothered me that Adolph was the name of my mother’s father in Brazil, and that my middle name was Rudolph. I didn’t want to hear or speak the pursed and guteral sounds of that language and neither did my parents. They addressed me and one another in the English they had learned before leaving Europe; but I cringed at the taint of their accents. No matter how bad Hitler had been, I was grateful to him for arranging that I would grow up expressing myself with the clean and odorless sounds of American. The Nazis’ nastiness provided me with the best of possible fortunes in the world–to be born in the U.S.A.

Things changed toward the end of high school. Being an American had become boring and uncool. I wore a beret, went to the Museum of Modern Art, and hung out in Greenwich Village where my friends and I listened to jazz and talked about Kafka and Freud. For my language requirement in my first year of college, I chose German. Its sound didn’t bother me any more–especially orchestrated by Beethoven and Bach–and I liked the fact that I could actually understand some of it, though I still couldn’t speak a word. There were some very cool Germans, and quite a few of them were Jews. And being Jewish was fine too, because it was cool to be an outsider and rejected by the herd. Nazis were just the German herd.

After a year of college, I went through my sophomore identity crisis. I was in a relationship with a girl I had met as a co-counselor in a summer camp for emotionally disturbed children. She was also the child of German Jewish refugees, a soulful, serious, and brilliant person whose mother had died when she was very young. We found infinite depth in one others’ eyes, but that depth kept filling with horror. We saw ourselves in the film, “Hiroshima Mon Amour”–the story of an affair between a victim of atrocities in France and a survivor of the bomb whose love was haunted by images of mass death. My images were blended from shadows of childhood and from what I was reading in my Contemporary Civilization course at Columbia. Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism made me begin to understand the scale of the Nazi crime. The intellectual effort it took to follow her dense political, economic and psychological analysis of the slaughter of millions forced me to absorb the reality of its horror in my mind, where I seemed to be able to suffer more than in my emotions or my imagination. I came to believe that the guilt was universal; not only was there no god, there was no good, there was no meaning, there was only chaos or self-deception.

I couldn’t sleep. I walked the city at night. I think I experienced some of the despair that finally drove people like Primo Levi and Bruno Bettleheim to suicide. I became obsessed with an image in a document quoted by Arendt called the Graebe Memorandum–an eyewitness’ description of a German soldier puffing on a cigarette while machine gunning rank upon rank of children at the edge of a mass grave.

The crisis passed after this relationship ended. I decided to become more healthy minded–to consciously resist the attraction of an abyss that was always close by. I didn’t realize it at the time, but this meant that I would no longer go out with Jewish girls. I fell in love with Europe when I went there the summer after my junior year–its cathedrals, footpaths and cafes. After six weeks of wandering through England, France and Switzerland, I finally made my way to Germany. With three years of language and literature courses at college, I could speak like a native, and I wanted to see the ones who had done it face to face. In one of the ancient beer-halls of Munich, where the Nazis did their first organizing, I struck up an acquaintance with a kid my own age in wire-rim spectacles and straight blond hair, a university student. His name was Eberhard Gloning. He was also staying in the youth hostel, and the next day he offered me a ride to Stuttgart, his hometown and that of my parents. His mother, father and sisters hosted me warmly for several days, while I walked around the town and countryside tracking down places in those old photo albums. There were no relatives left for me to visit, but the Glonings treated me like family. I called the darkly dressed grandmother “Oma,” just like my Oma in New York. Eating the same kind of apple pie she baked, one night at dinner I raised the subject of the Jews. It was a terrible tragedy, they said, part of the tragedy of the war and the starvation after the war. Hitler had brought about great suffering and they never liked him, but there was nothing they could have done. At that point I felt there was nothing I could do–neither condemn nor forgive. But at least, they didn’t have long teeth and I was not afraid.

Four years passed and I was in graduate school searching for a mate. At a poetry seminar in the Free University of Palo Alto I invited a girl who made smart comments to go to the pub afterwards. She looked surprised, then curious, and then agreed to get on the back of my Lambretta motorscooter. She worked with grape strikers in Delano on weekends and made costumes for the drama department. She grew up in Long Beach, but her Presbyterian family was from a small town in Missouri where they had lived for many generations. She had recently returned from a nine-months stay in Berlin and at a Stanford overseas campus located in Beutelsbach, a suburb of Stuttgart. She had gone to Germany because many of her high school friends were Jewish and she needed to confront the reality of Nazism herself. That night I knew my search was over.

If I try to understand the Holocaust, my mind gets dull; if I try to talk about it, my words sound hollow; if I try to divine its relevance to my life, I see everything and nothing. It’s much more comfortable to forget. That’s why I am here today.

****************************************************************

More material, uploaded December 26 2020:

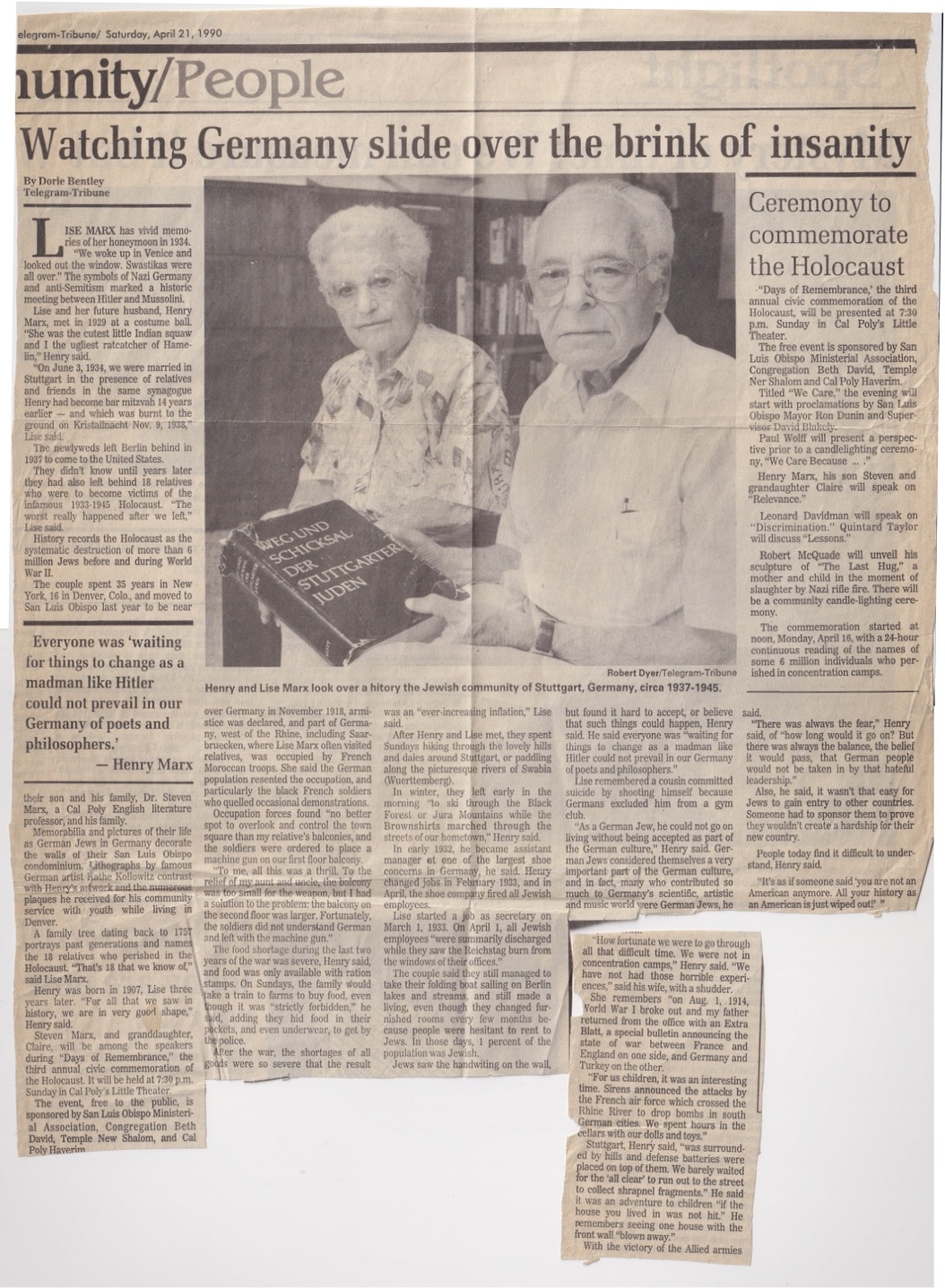

1. Newspaper article about this event

2. Text of Henry Marx’s and Claire Marx’s talks at this event [4-page pdf]

3. Fritz Rosenfelder’s 1933 suicide letter and response from friends.