The Path of Totality

Leave your stepping stones behind, something calls for you

Forget the dead you’ve left, they will not follow you

The vagabond who’s rapping at your door

Is standing in the clothes that you once wore…

The carpet now is moving under you

And its all over now Baby Blue.

Twelve people sat on the floor around a rectangular Oriental rug. The supper of brown rice and steamed vegetables was finished, and they were passing wooden bowls, chopsticks and teacups to the corner nearest the kitchen. The host, Peter Klein, straightened his back, crossed his legs, and took charge: “I’ve been reading about carpet designs. They’re all symbolic. The harder you look, the more meaning you find.” He felt warmed by the regard of his guests, mostly ex-students.

“For instance?” asked Ginnie, a thin young girl wearing a homemade beaded vest and strong wire rim glasses.

“See that outer border that looks like a row of crooked fingers?” said Peter. Those are waves. The sea surrounds everything. Now look at the next border with those jagged things alternating with those Y-shaped dealies. What do you see there?” As he used to in class, he waited out the silence.

“They look like pine cones and katchina dolls to me,” said Beth in a low, cultivated voice. Her mouth retained the suggestion of a slight smile, and she kept her eyes on Peter as if there were no one else in the room.

“Interesting idea,” he replied, but I think they’re actually heads of wheat and goblets, signifying harvest. Food and drink, the bread and the wine, communion.”

“I thought this was an Oriental carpet,” said Ramon, the art student whom Ariel had introduced for the first time tonight. There was a touch of irony in his voice.

Peter replied, “The rug is a Sumac. It comes from the Caucasus, on the border of Europe and Asia, where ancient trade routes and Christian, Moslem and Eastern cultures intersect. See these large cruciform shapes? They’re like the floor plan of a cathedral. And these feathery flames inside the crosses? They represent the Phoenix, the Arabian bird that dies every thousand years in a burst of flame and then is resurrected, like Christ.”

Peter stopped lecturing as he felt attention shifting toward the phallus-shaped pipe being lit by one of the guests. As the sweet fragrance filled the room, he centered himself between two diagonal axes of the Sumac pattern and waited his turn. The carpet was left to him by Tante Clara, his mother’s aunt. His wife Leona and he had recently agreed that apart from the bed, it was the only furniture they really needed. To simplify their lives and prepare for their eventual departure, they had sold or given away the rest, making most of their rent-controlled university apartment into a storage facility and crash pad.

Peter sucked on the pipe and passed it to the kid on his right. To avoid exhaling, he spoke in a high strained voice, ribbons of smoke curling around his words. “Eli, Annie says you do Tarot readings. I’m curious about that stuff. Could we try it while we’re waiting to take off?”

“Sure,” answered Eli, flashing an open smile and a chipped front tooth. He pulled a string bag out of his pea coat. “We lay out the cards in specified positions. You figure out what they mean. I can help if you want me to.” He withdrew a large deck of brightly colored cards and a small dog-eared book. “First you close your eyes and come up with a silent question you want answered.”

“A question I want answered,” thought Peter, exhaling with a sigh. For the last five weeks, ever since emptying out his desk in Hamilton Hall, there was a question all right. It hung him up like a meathook: “Where do I go from here?”

Peter opened his eyes and found himself staring into Eli’s. The lower part of his face was shielded by a fan of cards. From behind them issued a command: “Pick one and lay it face down.” Peter placed it over the flame on the carpet. “This is your Significator. It represents your sense of yourself. Now turn it over,” said Eli.

“THE FOOL” was printed in Roman caps at the bottom of the card. At the top was a large zero. On a ledge in front of jagged snow-capped-peaks a delicately featured young man stood with one foot in the air and his head thrown back. Peter recognized himself in this image. During his last year as a faculty member he’d delighted in playing the fool, writing scholarly articles about underground cartoonists, having students grade themselves, scaling university buildings at night. The student newspaper had run a feature story about him as the darling of campus freaks, a “boyish little man” whose courses provided “dessert for the academic gourmet.” And then he’d become a dropout, abandoned his tenure track position and taken up taxi driving–certainly a foolish move, but one admired by many of his colleagues as an exemplary act of protest against the university’s authoritarian structure and complicity in the war. Now he had a recurrent fantasy that he would return and cavort along College Walk playing his recorder. Students sitting in the grass would lay down their books, pick up instruments, and follow him. People in classrooms, looking out open windows on the warm spring day would notice, and crowds would stream out of the buildings and head off for the park and the river.

“Does this make sense to you,” asked Eli.

“Oh yes,” said Peter,” please continue.” The pipe had gone all the way around. Someone started gathering up the dishes. Others got up and stretched. Only four people remained in the circle of listeners.

“This next card is called the Cover. It pictures the situation that prompted the question.” Eli turned the card over and placed it squarely on top of the Significator. Peter saw a hand holding a silver chalice on its open palm emerging from a grey cloud surrounded by an aura of white flames. A dove carrying a small disk in its beak was descending toward the chalice, which overflowed in four arching streams that poured onto lotus flowers floating in a lake below. The caption read ACE OF CUPS. This image didn’t register. It reminded Peter only of a grotesque ceramic ashtray. He asked for the pipe and drew on it. A savage bite in his bronchials erupted into a cough, and at the same time the image exploded and reconstituted itself. “I see,” said Peter, “this is what prompts the question.” The disc was a pill. The chalice was his brain. This card represented his recent experience on LSD. It was still all there, making daily life seem trivial and absurd whenever he recalled it.

At the end of his last class, a tall girl had come up, kissed him on the forehead and slipped the pill into his hand. He swallowed it at midnight squeezed into a tiny dorm room along with Leona and half a dozen others, watching a student’s original eight millimeter film projected onto the door of a contraband refrigerator. At the end of the film someone had placed a pair of earphones over Peter’s head and said, “You’ve got to hear this.” At first he was immersed in the noise of surf: the swish of foam, the crash of breakers, and the hush of water withdrawing. Then he felt the sound as an immense barrage of molecular particles vibrating against his ear drum. The particles became bubbles that lifted and propelled him, waves within waves resolving again into sound, but sound that had color. With his own voice, from below his diaphragm, he was producing the sound, riding it like a winged horse. Changing pitch would change the colors. Then every pitch was sounding at once and the colors combined into white light. His intellect found words. This is it. All is one. God’s voice. In mine. Leona, the students, they knew, but they couldn’t know. One had said satori, she told him later, another called it glossalalia. They had read about these things in Peter’s course.

Peter came back to the carpet and the Ace of Cups. He felt Kent Stapleton’s conspiratorial stare. As usual Kent looked out of place with his short, well groomed hair, his tortoise shell glasses and Brooks Brothers clothes. Kent knew he was the only other one here who had been in the dorm room that night. When Peter had finished the sound, Kent had broken into sobs and begged to be healed. Placing his hands on Kent’s temples, Peter had let whatever was in there drain out through him, repulsed and a little frightened by this outward manifestation of the power he felt. After that Kent was hard to get rid of.

“Next card?” asked Kent, in a hushed, unctuous tone.

“Okay,” said Peter. Eli turned the top card and handed it to him. “This card, the Five of Cups, takes the Crossing position, representing influences that prompt the question running counter to those on the Cover card.” There was no lettering on the card, but even before Peter deciphered the image, its colors and shapes raised a caption in his mind: THE BUMMER. This was the name he gave to the recurrent bouts of depression over the past year that urged him as strongly as his manic gestures and ecstatic visions to change his life. He saw a full-length solitary figure dressed in a dark robe. Its front shoulder was raised, its neck was withdrawn, and its head was turned away. It made a black pillar against an olive-drab sky. In the background stood the grey ruins of a castle. Three of the five cups at its feet were knocked over.

The image intoned a familiar litany of reprimands: his paralyzed grandmother in the nursing home saying “get your shirt ironed,” his old rabbi saying “betrayer of the faith,” his ex-colleagues saying, “publish or perish,” his politico friends saying “bourgeois copout,” his own voice as his cab prowled the midnight streets of childhood neighborhoods in search of fares, saying, “you gave away your birthright, fool.”

Peter placed the card crosswise over the Ace of Cups, closed his eyes again and lowered his head. Suddenly he felt two fingers holding the pipe to his lips. He drew and then looked. It was Annie Greenberg. Her eyes were so dark one couldn’t distinguish the pupil from the iris and yet they radiated brilliance. “Do another one,” she said with a flip of her head.

Eli turned the top card and placed it beneath the crossed stack. “This card stands below. It represents the circumstances underlying the question.” Against a black sky and grey clouds of smoke, a fork of lightning struck a stone tower on a mountaintop. Flames exploded from its battlements and windows. A golden crown toppled from the tower’s roof, and two human figures plummeted into the darkness, fingers stretching, faces terrified. Its caption read, “THE TOWER.”

The violence of the image shattered Peter’s depression and recalled the satisfaction that he and his fellow radicals had taken in attacking institutions and bringing down rulers that oppressed them with the draft, the war, the industrialized system of education designed to produce corporate slaves. He remembered storming the towers of the University of California, the Hearst tower in Oakland, the Bank of America tower in San Francisco, the Pentagon towers in Washington, and he remembered the invasion of Low Memorial Library, when two of the people here had stood in the window of the President’s office, puffing on his Havana cigars, while its deposed occupant looked up in horror from below.

“The Tower is the card of Revolution,” said Eli.

Ariel picked it up and looked at it closely. She was trained as a concert violinist and had the most delicate fingers Peter had ever seen. “Up Against the Wall Motherfucker,” she said, flashing a wide cold smile.

Peter despised that phrase, which had become the slogan of the movement after the big bust two years earlier. It was the language of crooks and of the police. It expressed the frustration that had eroded their faith in non-violent action and that had split them into hippies and politicos. Last summer, pressured into joining the Weather underground, Peter and Leona decided instead to travel in Europe and North Africa. “Put it down, Ariel. Let’s move on,” Peter said.

Eli turned over the next card and placed it to the left of the stack. “This card is Behind. It signifies what’s passing out of influence.” A figure in red robes, bearing a huge triple crown, sat on a massive throne. On either side rose thick pillars topped by massive capitals. At the base of each, seen from behind was the tonsured head of an acolyte. THE HIEROPHANT, said the caption. Eli read from his guide: “The hierophant represents traditional teaching which is suited to the masses. He is the ruling power of external religion rather than the teacher of the initiated. He represents bondage to the conventional, the need to be socially approved.”

To Peter this heavy disagreeable image of the Pope looked like the statue of Alma Mater. Dominating the central plaza of the campus, flanked by the granite pillars of the administration building behind and staring at the granite colonnade of the library in front, Alma Mater with her book on her lap and her owl in her robe was the soul mother of the university. He had been admitted to her precincts the first day of freshman week, and, four years later he’d sat at her feet as the college dean concluded his commencement address with a blessing and exhortation to “Keep the Faith.” But by the time he came back to teach in the late Sixties, that old faith had given way to a new one. And so, at the foot of Alma Mater, during a massive protest rally last October, he’d announced his resignation in the words of a Bob Dylan song: “I aint gonna work on Maggie’s farm no more… ”

To end his last course–“Pastoral and Utopia: Visionary Conceptions of The Good Life”–he had planned a three day Final Exam Festival in the rotunda of the university interfaith center. The doorway was framed with a cardboard Omega, representing Apocalypse and Resistance. There were plays, films, lectures. The hall was crammed with student projects: poetry, paintings, sculptures, photographs, a huge teepee made of plastic inflated by an electric fan. To conclude the event Annie and Ariel had organized a bread ceremony. It began with talks on the chemistry of leavening and baking, nutrition, and small scale agriculture and economics. Then lights went out, candles were lit and thirty loaves, hot from ovens in nearby apartments, were distributed to the hundred and fifty people sitting in a circle. As the loaves were broken, steam and fragrance erupted throughout the room, someone started playing the flute, and three young women got up and danced in a circle around the candles. Peter had walked out the door, no longer, he reflected now, in the sway of the Hierophant.

“You ready to go on?” asked Eli.

Peter nodded and switched positions so that he was sitting on his haunches.

Eli slipped off the next card and placed it above the crossed stack in the center. “This is the crowning, a possible outcome of the present situation.” THE EMPEROR, a bearded, armoured man, sat on a stone cube above a river. He held a sceptre and an orb. He was poised to move. This figure represented the kind of authority Peter could respect. His power was his own, not conferred, power like Ken Kesey’s, the master of fiction who drove a band of Merry Pranksters around the country on a bus called “Further,” or Stephen Gaskin’s, the philosophy instructor whose Monday night class at San Francisco State University turned into a pilgrimage to a utopian community in Tennessee. Such leaders could channel their visions into action. They could cope while hallucinating, they could drive while high.

Peter knew he could do that. He’d once driven five people back from a trip to the Blue Mine through rush hour traffic on New Jersey’s Route Four. He had the knowledge and the courage. That’s what his students really wanted, not grades and credits. That’s why his apartment was full tonight. He was holding the orb and sceptre. Their heft felt good in his hands. That’s why he was given those visions.

Peter felt something inflate inside his skull. Could he break into utterance now and show his power? But wait, what if it didn’t work, or they didn’t get it? How could he rule anyone else, if he couldn’t rule himself? This was all only a desperate substitute for what he’d lost. Where the hell was Leona?

“Eli, I’ve had enough Tarot,” Peter said. “Let’s finish another time. It’s getting late and we need to start packing for the trip, so that we can leave if Leona ever gets here.”

“You can’t stop a reading in the middle,” said Eli. “It’s terrible karma. Take it easy, don’t spend so much time on every card. Let them just go by so that you can put together the big picture.”

“OK,” said Peter, but wait a minute, I need to pee.” He got up on creaky legs and made his way to the bathroom. He searched the mirror for that boyish face, for Nature Pete, his nickname as a counsellor at Camp Moonbeam ten years earlier. But what he found were wrinkles under his eyes, a lengthening nose, an excessively high forehead topped by a huge shock of hair that couldn’t decide if it was wavy, kinky or curly, sticking out in three bulky masses. He’d better get a grip now, there was no one to depend on.

He followed Bernie and Rachel back into the living room. They were carrying bowls of grapes and walnuts. As soon as he sat down, Eli lifted a new card and laid it to the right of the center pile. “This card is placed in the position of what’s coming into influence. It’s the Four of Wands.”

A May Fete was being celebrated on a bright meadow by shepherds and shepherdesses. While ewes grazed and lambs gambolled on the greensward, two young couples danced in the foreground bearing garlands of flowers and gripping long wooden sticks which sprouted buds and blossoms. This is what Peter wanted to see. His unfinished doctoral dissertation was a history of the ideal of innocence in pastoral poetry. As his research had proceeded, the tradition he was studying suddenly resurfaced in the poetry and songs of his own contemporaries. Not only that, but people were acting out the vision. Leona and he had spent the summer before last camping in the pasture at a commune in Vermont. After scything hay or frolicking in the Beaver Pond with the rest of the group, they’d retire to their tent where Peter wrote out endless paragraphs on the structure of Edmund Spenser’s The Shepheardes Calender and Leona transcribed them on their portable typewriter. But his advisor didn’t approve and Peter had lost interest in footnotes.

The sound of a siren shrieking down Amsterdam Avenue filtered in through the the air space and the living room window. Peter heard the front door unlock, and in walked Leona, laden with books, a swollen briefcase and a large shoulderbag. She looked haggard. It was the end of another long work week at the private high school for gifted drug-involved underachievers where she taught English. To several greetings of “Hi, Leona,” she replied, “Hi, everybody,” and to Peter she said, “Sorry I missed dinner. Glad you didn’t leave without me. I had to stay till nine to lay out the pictures with the student photographer. That kid is such a pain. But the yearbook is great and ready for the printer.”

“Good,” said Peter. “Eli is doing a Tarot reading for me. It’s amazing.”

“I’ll be back in a minute. Let me put my stuff away and change,” she answered.

There was a flurry of telephoning and food preparation in the kitchen. Back on the carpet, Eli had already turned the next card and placed it directly to the right of the Tower card in the position he called “Hopes and Fears.”

“Both at once?” asked Peter.

“Yes,” said Eli. It pictured a man and a woman from behind, each grasping the other around the waist and extending one arm upward. A stream flowed toward them, passing a thatched farmhouse nestled in a grove of trees. Two children danced in the foreground, holding hands and kicking high. A rainbow arched over the scene supporting ten full goblets. Clearly an image of prosperity and fulfillment, but it sent a chill through Peter. This was not his pastoral. There weren’t just boys and girls, there were parents. His parents lived in the Bronx. They wanted grandchildren. He didn’t want to think of parenthood and family. He wanted community and childhood.

With her hair to her waist, wearing a pair of heavy filigreed earrings, wool navy bell-bottoms and a denim work shirt, Leona came back into the room and sat at a corner of the carpet. Peter liked her dressed this way better than in the suit she wore to work.

“Are you ready, man, this is the last card, the Outcome. It answers your question,” announced Eli, so that everyone could hear. They straggled back into the room and gathered around the carpet till all attention came to rest on Eli’s hand. He lifted the card and handed it to Peter.

The image struck him like a blow. Inside a chapel where everything was greenish-gray, a bareheaded knight in armor lay on a sarcophagus, eyes closed, hands clasped in prayerful repose. A sword was mounted horizontally below him on the side of the coffin. Three swords on the chapel wall pointed downward toward his body. In the upper left corner there was a brilliantly colored stained glass window depicting a mother and an infant. The Outcome. His own funeral. A wife and child watching over his tomb. They were striken with grief. They were unprotected. He had forsaken them. He saw a gulf in front of him and felt a grip in his chest. Would it happen tomorrow? Tonight? His hand lowered slowly and he dropped the card on the rug.

Eli and Leona both sensed his distress. “Don’t take it so seriously,” she said, “it’s just a deck of cards.” Eli went for the book. “Look, man, this isn’t what it seems. Swords mean pain but also the intellect making distinctions, clarifying, cutting bonds to matter, illusion or ego. The four of swords is definitely not a death card. It says right here, ‘Rest from strife, retreat, exile. Not a card of death.'” He repeated, “Not a card of death.”

Peter tried to absorb this information, but it could not reduce his terror. He felt lost and isolated in the room full of busy, excited voyagers. He had forgotten why they were there, where they were headed. Leona tried to put her arms around him as he got up, but he asked to be left alone for a while and climbed over the pile of sleeping bags and packsacks on his way to the bedroom. He sat on the bed, on top of the laundry. The outcome card remained in his mind. “I’ve left them alone, I’ve gone.” He wept. The emotion passed. Then he asked himself, “Who are these people? That’s not me. I have no child.” He heard Eli’s voice, “This is not a card of death.”

Leona opened the door quietly, walked over and placed her hand under his chin. She said, “You seem to be doing all right now,” went to the closet and took out her insignia-laden World War II army jacket and a long shimmering shawl she had bought in Tunisia. “It’s ten to eleven, almost time to go.” From outside he heard people loading packs and getting dressed, the door opening and closing. Peter bounced off the bed, put on his leather jacket and stocking hat, and followed Leona out of the room.

Giggling and shushing, they moved as a pack down the tiled hallway and crowded into the elevator. When the door opened to spill them out into the lobby, they almost bowled over a tall, severe-looking hornrimmed man in a black overcoat. “Vat are you students doing here,” he barked.

“It’s all right, Doctor Denkerman, these are my guests,” said Peter as he held the elevator door from closing on the man whose books on the history of philosophy he had spent long hours studying in preparation for his comprehensive exams.

The doorman ushered them into the freezing March night. “Going on an expedition, eh Professor,” he asked Peter.

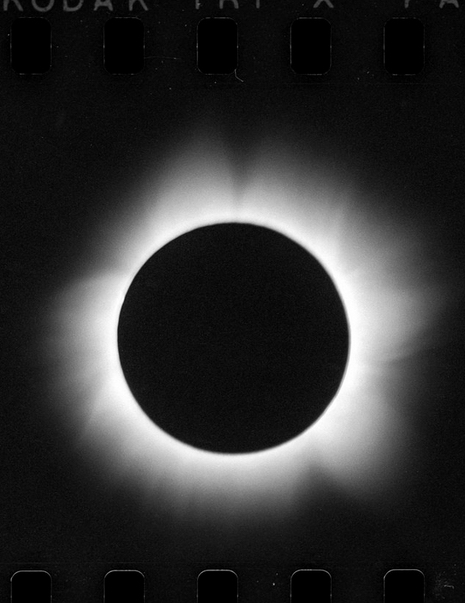

“Yep, Sonny, we’re off to Cape Cod to see the total eclipse of the sun.”

“Well take care, and have yourselves a good time.”

Out on the street, while Gerry passed the pipe and others stamped to keep warm, three vehicles were loading–a lumbering Pontiac, with a driver Peter hadn’t met, Bernie’s VW van, and the white Renault that Leona and Peter had bought with the thousand dollars he had recently inherited when another old aunt had died.

Peter tried to hold Annie with his eyes as he asked, “Do you want to go with us?”

“Uh, uh,” she laughed and grabbed the arm of a tall baby faced pre-law student with a Boris Karloff brow. “I’m going in the van with Ron.”

Kent, Beth and Ginnie climbed into the cramped back seat of the Renault. Peter conferred with the other two drivers. “We take the Cross Bronx Expressway, Connecticut Turnpike, and Route 6. Let’s caravan, but if we get separated, we’ll meet at the traffic circle in Orleans.”

At midnight there was little traffic on the Triborough Bridge. Looking down on the city through the whizzing cables, Peter relished the moment. The companionable taillights of the two cars ahead on the empty bridge proved that people would come if he gave the word. He recalled the afternoon ten days earlier, playing follow-the-leader with Annie in Riverside Park, hanging from tree branches, balancing on rock walls, bouncing on the see-saws. She had just won a poetry contest, but the officials wouldn’t let her into the award ceremony because she was wearing dirty jeans and ragged tennis shoes. Both winded, they had sat down on a bench next to a folded copy of the Times and looked over the front page. In the lower left corner was a picture of the sun’s corona and the headline, “Scientists Prepare for March 7 Eclipse.” The path of totality just grazed the easternmost beaches of Cape Cod.

“Wouldn’t it be neat to go see it?” he had said.

“We could get a bunch of people together again, like at the festival,” she’d replied.

“We could leave on Friday night, get there in time for the eclipse on Saturday noon.”

“Ariel has friends whose parents have a place on the Cape near Orleans.”

“Bernie has a bus. We have our Renault. That’s a start.”

“Maybe Gerry can get some mescaline.”

Now he was on the Cross Bronx Expressway. Against the bad pavement, the tires made a brapping sound that echoed from the walls of the concrete moat. Peter pushed “play” on his new portable stereo tape recorder, and they all sang “Cousin Caterpillar” along with the Incredible String Band as the car passed out of the city limits:

My cousin has great changes coming

One day he’ll wake with wings.

They were off to the Cape, a real place that had seemed out of this world ever since he had hitchiked there with his buddy after their sophomore year in high school. You could camp just about anywhere on its miles of deserted beaches, sandcliffs, rolling heaths, hidden lakes. You could build a shack out of driftwood, pick berries, get drunk on vodka in seven-up bottles under the moon. In Provincetown, at the tip of the spit, you could find a small city of people who took pride in doing whatever they pleased. The previous spring he and Leona were invited by another couple to spend a weekend at a run-down old cabin near Wellfleet called “Boozer’s Bunkhouse” owned by some relatives in the Midwest. After a day of skinny dipping and sunbathing they had moved all the mattresses and sleeping bags together in front of the fire, and they’d spent the night cuddling in playful combinations. Nothing further came of the incident, but it gave substance to the libertine fantasies that Peter had documented in Renaissance poetry about the Golden Age and in Reformation tracts about the Family of Love, a sixteenth century religious cult that sought to repair the effects of the Fall through the practise of communal sex. In his course he had assigned an elegant pornographic novel about a guru named Max who teaches his followers how to satisfy all their desires without jealousy or guilt. Its setting was the Cape. The higher you got, Peter thought as he fumbled in his canvas travel bag to get out his pipe and stash, the greater the number of coincidences. There was no such thing as an accident.

At about 2:30 A.M., the Pontiac and the VW bus pulled off at a Turnpike service station near the Rhode Island border and Peter followed. As the attendant approached, the three vehicles emptied out. People ran to the toilets, jumped up and down in the cold and dug in their pockets for gas money. A few minutes later the caravan reentered the sparse flow of traffic, beeping and flashing. Across the marshes ahead, Peter saw the lights of a bridge rising above an arm of the sound. At the upgrade he followed the lead vehicles, changing lanes to pass a laboring truck. Suddenly the car lost power. As the truck in the right lane pulled ahead, he floored the accelerator, but the engine coughed and died. He depressed and released the clutch. The engine resisted, but wouldn’t start. He shifted into neutral and turned the key, but there was no ignition. It felt like running out of gas, but he had just filled the tank. Something strange was going on.

There was no right shoulder, just the bridge railing. On the left, nothing but the corrugated median divider separated them from oncoming traffic. In the rear-view mirror he could see a car approaching in his lane. He turned on the flashers. The car swerved to the right, cutting off another pair of headlights, and sounded a howl in passing. As the Renault rolled to a stop in the left lane, Peter caught a glimpse of the VW bus disappearing over the top of the bridge. The traffic on both sides whizzed by fiercely while the tape recorder in his lap played “Mercy I cry city”:

You cover up your emptiness with brick and noise and rush.

O I can see and touch you but you don’t owe reality much.

The right lane was filling with lights. He turned the key again. No ignition. The flashers ticked like a time bomb.

Leona said, “Let’s get out.” She walked back along the center divider signalling traffic to move right. Peter ran across to the railing and uphill to look for an emergency telephone, but there was none. He came back to the car and found Leona and the others huddled and shivering beside it. The traffic had increased. Horns were blasting in the green mercury vapor light. The backdrafts from the trucks bounced against the wind from the river. Better to take shelter inside the car than be blown off the bridge or hit by flying wreckage.

They climbed in and fastened their seatbelts. Peter shifted the stick into neutral so that the impact from behind could be absorbed by their rolling forward, and he put on the emergency brake just enough to keep them from rolling back. A pair of headlights in the mirror grew slowly, then quicker, then swerved like the last one and merged with the line of glare in the right lane. Missed that time, but soon. He felt a presence inside the car. The Outcome card. Not frightening now, familiar. For some reason the five of them had been selected. A single light in the mirror divided in two and brightened. The eyes of the angel of death, the whir of the Bridegroom’s chariot. His fate was no longer his own. No more need to choose, to act, to regret. “We are all in your hands,” he thought, “I am ready.” He pressed “play” and the red record button.

Then Leona turned her head and looked through the rear window. “Here it comes,” she shouted. There was a massive crunch, a momentary sense of weightlessness, then a thud and silence. Peter felt as if he’d been shaken like a rag doll and dropped. They were still on the bridge. Not dead, not even bloody. There was talking. People were asking each other if they were OK. It was cold and loud. Lights whizzed by on either side. Another vehicle, it looked like an old Cadillac, was stopped forty or fifty feet behind them. The Renault had been propelled through the air, had landed and coasted forward. The passenger compartment was intact except for the smashed rear window, and now they were shielded by whatever hit them against any more threat from behind. There might be a pileup, but they were safely out in front of it. Peter felt an onrush of excitement. It was a genuine miracle. They’d flown, in the car. He had faced death again, and this time it was friendly. They must all be joyful to know life at its very edge, to feel the power that can take and restore it.

They got out of the car to examine the damage. The engine in the rear of the Renault was crushed.

Ginnie leaned against what was left of the fender and said her back hurt. Leona said her neck felt twisted. Kent sat on the curb crying. Beth was quiet. They could see two young men in sailors’ uniforms get out of the car behind, laughing and staggering. There was a squeal of brakes and the sound of another collision further back.

Peter pulled the stereo out of the car. “It’s still recording,” he said to Leona. “I think I got it all on tape.”

“Can’t you see this is serious?” she said. “Open the hood so I can get out some blankets.”

Then Peter heard a siren, and a highway patrol car and a tow truck pulled up between them and the sailors. More sirens and flashing lights approached. The traffic slowed. Another towtruck pulled up in front of the Renault. The driver came over and said there were no injuries in the other two cars. Their stall was probably due to a block in the fuel line caused by temperature change, something called vapor lock. A state trooper walked up the pavement and Peter thought about the stash in his bag. The officer looked at the damage and said that they would have to go to the police station to fill out a report, though as a victims of a rear end collision they were clearly not at fault. The Renault was on the way to the junkyard, just one more possession gone. The flourescent red cones and sparkling flares that appeared in the middle of the road celebrated their rescue.

It was raining by the time they were reunited in the precinct house in Pawtucket Rhode Island. Peter had buried his pipe in the trash container in the men’s room and stuck the chunk of hash in his sock. Slouched on their sleeping bags safe and warm, munching sprouts and tofu, listening to the soothing sounds of John Fahey’s twelve string guitar, they weren’t eager to leave, but they had to make a decision. Leona was concerned about her neck and Ginny’s back. They could stay here in a hotel. Kent wanted to return to New York immediately by train. Peter insisted they press further. That’s what this was about. You’re on the bus or you’re off it. There was still time to take up the pilgrimage and witness the eclipse. If they could only get there, the accident would become an essential part of the story. The image of the others waiting for them at the traffic circle in Orleans drew him like a beacon.

“I’ll call you a taxi,” said the officer on duty. They repacked their bags, and ten minutes later a battered yellow Plymouth pulled up outside the police station. Peter explained their predicament to the longhaired driver.

He sympathized. “It’ll take me five hours to get there and back. I can’t do it for less than fifty bucks,” he said.

That was only ten dollars apiece. They could swing it. Peter and the three women rode in the back seat. Kent went in front. As they rolled past the old brick factories of Providence and Fall River, they listened to the tape of the crash over and over again and dozed. Peter worried that their rendezvous time at the traffic circle had passed. What would they do when they got there, not knowing where the cabin was located, with nobody to tell their tale? But the weather was clearing. Just as the sun emerged from a cloudbank, the road split into the Orleans circle. Not a soul in sight. Peter asked the cabbie to drive all the way around before letting them off. Attached to the huge green and white highway billboard he noticed a small hand-lettered piece of brown cardboard. As they approached, it became legible: “Peter K. wait here.” A little picture of an eclipse was drawn in the corner.

Peter recognized Bernie’s crabbed handwriting. He felt a surge of affection for the impish undergraduate whom he could never think of as his student, even though Bernie had taken two of Peter’s courses. Another only child of German-Jewish immigrants, he seemed like a younger brother, more adventurous, less intellectual, but leading a parallel life. Just then around the circle chugged the VW van that he had watched disappear three hours earlier. Bernie popped out and said,” I’ve been checking every half hour. Where’ve you guys been?”

The house to which Bernie drove them down a sandy road bordered by pines was in a state of groggy confusion after a night of very little sleep. People were briefly fascinated with the tale of the accident, but then distracted. Annie was feeding raisins to Ariel’s art student, Ramon. Ariel followed baby-faced Ron out of one bedroom. Peter went into the yard where the sun was glancing off Ginnie’s bare back as she lay on a large grey rock. Her spine was still hurting, she said, so he offered her a backrub. He looked at the flattened curve of her breast showing above the rock, kneaded the tensed muscles and then left his relaxed hands on her shoulder blades, trying to draw off the pain.

Beth came over. “Teaching and healing,” she said, staring at him. He looked through Beth into the house, checking on Annie. It was solace just to be in the same place with her, to hear the childlike mischief in her voice and to glimpse her heartbroken clown’s eyes.

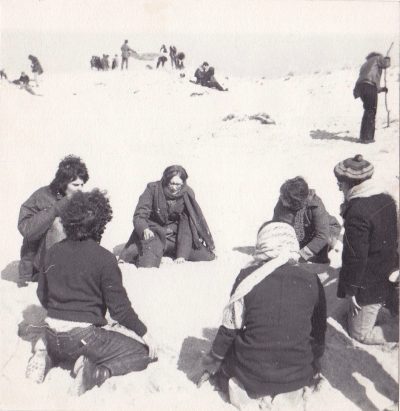

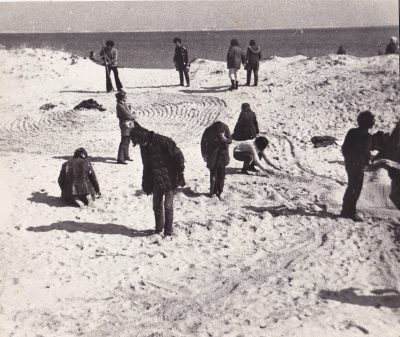

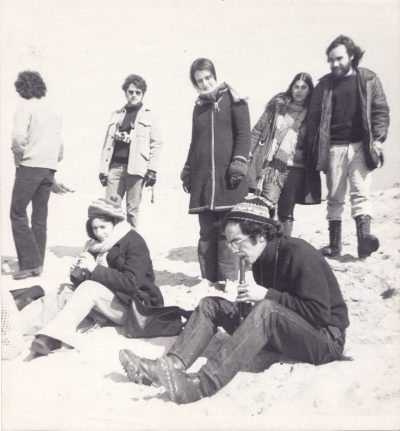

Annie came out and announced it was time to head for the beach. The thirteen of them had to fit into two vehicles for the short ride. They parked at the top of a cliff by a bank of radio antennas and wandered down another sand road toward the water. Gerry went from person to person handing out capsules and the pieces of exposed film recommended on the news for eye protection. Peter swallowed the pill. Then he looked through the black celluloid at the smoky white circle. A little bit was shaved from the right side. It had already started.

Strangers were crowding down the road to the ocean now, surrounding their group. It would be better to move along the beach to a more secluded spot, he thought, and he led them along the shoreline to the north, following the snaky weave of the foam. Behind the high tide line of packed sand, the beach became pitted with craterlike hollows, a hundred feet across, five or six feet deep. They clambered into one and claimed it as their own territory. From inside, no other people were visible. It was a private self-enclosed space, oriented only to the sky.

It felt good to move. Peter liked the sand compacting under his boots, the chilled air streaming along his cheeks, his undershirt and pants stroking his skin, his calf and thigh muscles tightening against bone, levering the tower of his skeleton forward. And it felt good to stop. He could release the tension in those muscles and the tower collapsed in a heap on the ground. He scooped up some sand and hefted it in the cup of his palm. Then he flattened his hand and felt the flowing friction as it spilled through his splayed fingers into a small rising cone. The pile became a white triangle outlined against its own triangular shadow. All around him, shadows and bright spots laid a pattern across the soft sand like a quilt. Peter remembered the shadow of the moon and looked through his film at the sun, now almost a quarter obscured.

He saw Ginnie walk to the middle of the hollow and get on her knees. With her woolen gloved hands, she smoothed a circular space about six feet in diameter, drew the rough outline of a face, and surrounded it with a low dike of patted-down sand.

Leona approached contemplatively. With the toe of her boot, she dug a thick wavy line from the dike toward the rim of the hollow. Opposite her, crouched Kent. Moving backward on his haunches, he shaped a vegetative tendril that grew outward, a second ray. Ron started a third with a Chaplinesque  shuffle that left a herringbone impression extending inland. Near the seaward edge of the hollow, Ramon took a long stick and began methodically tracing a snail-like spiral of ridge and groove around itself and outward. Peter got up and walked in a circle, watching the distances between the slowly moving bodies in the sand gracefully rearrange themselves.

shuffle that left a herringbone impression extending inland. Near the seaward edge of the hollow, Ramon took a long stick and began methodically tracing a snail-like spiral of ridge and groove around itself and outward. Peter got up and walked in a circle, watching the distances between the slowly moving bodies in the sand gracefully rearrange themselves.

When he came back to the place he’d been sitting before, he took out his recorder and started to play. As if gripping a rope tow, he was suddenly yanked into motion by a torrent of melody flowing through his diaphragm, lungs, throat, lips and fingers into the wooden tube and through its eleven holes out into the air.

When he came back to the place he’d been sitting before, he took out his recorder and started to play. As if gripping a rope tow, he was suddenly yanked into motion by a torrent of melody flowing through his diaphragm, lungs, throat, lips and fingers into the wooden tube and through its eleven holes out into the air.

Annie appeared on the rim of the crater, outlined against the sky, undulating and whirling in synch with his playing, the tails of her scarf and her hands outflung, her face expressing inward concentration and furious joy.

Annie appeared on the rim of the crater, outlined against the sky, undulating and whirling in synch with his playing, the tails of her scarf and her hands outflung, her face expressing inward concentration and furious joy.

Bernie and Rachel entered the hollow from the ocean side, holding hands like children in gradeschool, glancing at each other and then looking at their feet. They locked elbows and started to dance, spinning their way down to the center where Ginnie sculpted. They revolved in orbit around her sun while Beth sang in a shimmering alto voice, improvising against the recorder’s melody, the waves’ beat on the beach, and the cries of seagulls. After a time the melody ceased and the dancers dropped. Peter put away his instrument and watched Ginnie’s sun rise.

The plump Buddha cheeks and the full lips, parted in a slight inward smile, swelled into mounds and cast deeper shadows. The face detached itself from the sand that molded it and radiated a golden warmth. Then it slowly dissolved into the black and white pattern of highlight and shadow.  Soon it reemerged, but this time its features were concave, as if on a photo negative or a mask seen from behind. Ramon’s spiral had become a great circle of concentric rings approaching it.

Soon it reemerged, but this time its features were concave, as if on a photo negative or a mask seen from behind. Ramon’s spiral had become a great circle of concentric rings approaching it.

Shadows were lengthening everywhere, heightening contrast, bleaching color, and coarsening the grain of the landscape. The sky had a pinkish-purple tinge. Though it was around midday in March, it seemed late afternoon in December. And the change itself was becoming discernible. Rather than fading as at dusk, the light was thinning. Peter felt cold. He saw Leona dragging a twisted piece of driftwood toward a pile of sticks and shavings she had collected at the bottom of the hollow, in back of Ginnie’s sun. Kent and Gerry were hauling in more wood from the direction of the cliff.

As he walked around toward them, Peter saw Ramon join the others for the first time and throw his stick on the pile. The spiral had reached the edge of the sun. Peter made a quick pass across the sky with his eyes. The after-image on his retina was a jagged wound of melted gold. Then he looked through his exposed film and saw that more than half the disc was gone.

Leona lit a match under the kindling and reddish flames from the salt-soaked wood crackled and flashed.  The thirteen people dispersed in the hollow were drawn into a circle around the fire, warmed and reassured. It was tribal custom during eclipses to build bonfires and create images to replace the sun and lure it back, reported Leona.

The thirteen people dispersed in the hollow were drawn into a circle around the fire, warmed and reassured. It was tribal custom during eclipses to build bonfires and create images to replace the sun and lure it back, reported Leona.

Peter left the circle to make another tour of the hollow.  He walked up near the edge, and for the first time since they arrived, he looked outside. In both directions along the beach there were hollows like theirs with groups of people standing around fires sending up parallel pillars of blue or black smoke into the greyish violet sky. In a smaller hollow back toward the cliffs, four young people sat on a blanket eating with chopsticks from wooden bowls while a baby crawled between them. They were fellow pilgrims, in their own world, just over the mound of sand. As Peter approached, a girl with long straight hair in a tie-died skirt and a surplus army jacket stood up, lifted the lid of a black pot cooking on their fire, and invited him to share lunch. The pot was filled with vegetables and brown rice.

He walked up near the edge, and for the first time since they arrived, he looked outside. In both directions along the beach there were hollows like theirs with groups of people standing around fires sending up parallel pillars of blue or black smoke into the greyish violet sky. In a smaller hollow back toward the cliffs, four young people sat on a blanket eating with chopsticks from wooden bowls while a baby crawled between them. They were fellow pilgrims, in their own world, just over the mound of sand. As Peter approached, a girl with long straight hair in a tie-died skirt and a surplus army jacket stood up, lifted the lid of a black pot cooking on their fire, and invited him to share lunch. The pot was filled with vegetables and brown rice.

The girl scooped food onto a plate and passed it. Peter lifted some rice with two fingers and let it rest in his mouth. Saliva burst from under his tongue and his cheeks, rinsing the creamy starch that held the grains together down his throat in a rich bisque. He started chewing slowly, feeling his molars grind the soft but resistant kernels and his front teeth crunch the fibrous bran coats that remained. Above them the sky relinquished opacity and began revealing its depth. The sun was in its last quarter. One could look at it directly for a second, the dazzle now silver rather than gold. He swallowed and invited the new companions to join the larger group in the next hollow.

From the ridge on the way back, he could see there were fewer and larger circles than before. People were migrating between hollows, taking firewood with them. His own was filling with strangers. The rate of change was accelerating. Everything was moving, as if centrally directed, like a flock of birds. Hundreds of gulls reeled and clamored overhead, and the shore break of the surf marched up the sand, pulled by the same tide that affected his brain–the sun, the moon and the earth approaching perfect alignment.

Back down in the hollow, a diverse crowd assembled around the fire: teenagers, families with children, some grey haired people, a few blacks, a bunch of fraternity-sorority types and more student hippies. Peter’s own group had dissolved, but Ginnie remained between the growing fire and her sun, protecting it as the darkness thickened. The people in the circle joined hands and started moving counterclockwise. The sound of Om arose from several points and then converged in a steady chant.

The approaching breakers thumped on the sand and then flattened. The wind died. The gulls quieted and alighted on the water. Daylight drained from the air. A dog barked. When the dark moon swallowed the last sliver of brightness, people broke the circle around the fire and ran to the ocean. The moon’s shadow raced toward them across the glassy surface of the water. Under them now, they could feel the earth’s swift rotation and they cried out. As the shadow engulfed them, the cry became a scream.

When the dark moon swallowed the last sliver of brightness, people broke the circle around the fire and ran to the ocean. The moon’s shadow raced toward them across the glassy surface of the water. Under them now, they could feel the earth’s swift rotation and they cried out. As the shadow engulfed them, the cry became a scream.

Then there was silence.

Night.

Stars.

A black disc encircled by tiny orange flames and a white shock of radiance.

For two or three seconds Peter saw it, before he was forced to turn his eyes from the retina-burning blaze emerging from its mask. A breeze ruffled the surface of the water. The gulls stretched and flapped their wings. A small wave broke. The stars were gone and the sky was opaque again with a grey-pink surface. He extended both arms to greet the returning sun, and from either side he heard cheers and applause. At the water’s edge, he could see a single line of people extending from horizon to horizon.

As the tide retreated and the light returned to normal, the unbroken line fragmented into discreet groups. Peter returned to their hollow. People were walking through it back toward their cars, animated and boisterous like after a ball game, unaware their footprints were obliterating Ginnie’s sculpture. The fire was a pile of embers.

Next morning’s departure from the cabin in the pines was somber. The Pontiac had left the previous night for Boston, and those who remained were not eager to head back to New York. They packed the VW van, stashing the Coleman stove and the pots and tools under the small shelf in the very back and pooling all their bedding to make a nest on the floor that eleven people could ride in comfortably. Bernie was driving now. Leona sat next to him to keep her neck straight, while Peter rode in back. He liked being a passenger, not even seeing out the window, part of the group bunched together like the pilgrims and exiles in the Crosby, Stills and Nash song coming from his lap:

Wooden ships on the water very free and easy

…

We are leaving

You dont need us

If they were only heading North, Peter mused. Toward New Hampshire, where Linda’s parents were willing to let them live on their land, to Vermont where there was more room at Packers Corners, to Maine, where Herb and Edie had set up shop as jewellers, or to Canada where you could get land cheap and there was no war, no draft, no assassination, no bombing and no racial crisis.

Three or four times, Bernie stopped the van and rattled around in the back. Now, over the sound of the motor and the music, Peter heard him shout, “Look car, I’ve given you all the oil I have, so you can damn well do without it. Forget your stupid red light.” A few minutes later a loud clanking noise came out of the rear of the bus, and then the motor was quiet. Bernie pulled to the side of the road, tried to start again with no success, and pounded on the steering wheel.

“I think you blew up the engine,” said Ramon.

Another sign, thought Peter. We may not make it back after all. While Bernie tinkered disconsolately under the back flap, they all piled out and stood around the van, once more helpless. It was 2:30 and starting to rain. A large suburban station wagon passed by slowly, and its driver leaned across the right hand seat looking them over. It continued ahead for a hundred yards, then pulled to the shoulder and backed up. A small grey-haired man in a raincoat and rimless glasses got out and approached the van.

“What’s this?” asked Annie.

Leona said, “Looks like a Presbyterian minister to me. I grew up with them.”

The man searched their eyes and then addressed the whole group. “My name is Parker Wainwright. I’m pastor at the First Presbyterian Church of Pawtucket. May I be of any service?”

At first no one answered. Then Peter said, “We travelled from New York to Cape Cod to see yesterday’s total eclipse. This is the third vehicle we’ve lost.”

Bernie asked, “Is there a mechanic around who could work on my van?”

“There’s no chance of that on Sunday,” the minister replied. “But if you like, I’ll pull it to a garage, and I’m sure the congregation wont mind if you stay in our church as long as you need to.” He rummaged in the suburban and dug out some heavy frayed rope. Ramon scuttled underneath and tied it to the frames of both vehicles. Bernie steered the dead VW, while the others climbed into the station wagon.

Half an hour later they got out in the courtyard of a modern church complex on top of a hill. The minister led them past the imposing facade through an arcade into a domed octagonal meeting room at the back. “Make yourself at home,” he said with an open-handed flourish. “I’ll be back later.”

Stunned, they looked around the hall. The place reminded Peter of the rotunda in the interfaith center at the university. Several classrooms and a kitchen opened on to it. Quotations from the Bible illustrated by children decorated the walls:

He that findeth his life shall lose it: and he that loseth his life for my sake shall find it.

Behold the fowls of the air: for they sow not, neither do they reap, nor gather into barns: yet your heavenly Father feedeth them.

If ye have faith as a grain of mustard-seed, ye shall say unto this mountain, ‘Remove hence to yonder place’; and it shall remove; and nothing shall be impossible unto you.

“Here we are in Sunday School,” Peter said. “Let’s cool it on the drugs.”

It was getting dark outside. Ron started a fire in the stone hearth. Ariel went into one of the classrooms, and came back carrying a guitar. Ramon went into another classroom and found some cloth and brightly colored thread in a cupboard. He sat down and started embroidering what looked like a sunburst. Ginnie followed him, put on a spattered smock hanging from an easel, opened jars and began painting overlapping circles. Annie went into another room, where she picked an empty notebook off a shelf and sat down at a kid’s desk to write. Peter followed her, saw she was occupied, and went over to the storage closet. What should he make? He noticed some folded pieces of white muslin and boxes of RIT dye. A flag of the corona against the star filled sky. The week before, Beth had shown him how to batik with melted crayolas. In the background he heard Ariel singing Joni Mitchell’s “Woodstock”:

We are stardust

we are golden

and we’ve got to get ourselves back to the garden.

Leona found the phone and called her school principal to say that she couldn’t come in on Monday. Then she went to the kitchen, assembled food and utensils, and began mixing up bread dough. Bernie brought in a box of vegetables.

Two hours later, drawn by the smell of fresh bread, they were all sitting under the dome around a large votive candle that Peter had lit in the center of the room. Annie read out her poem:

remember to turn out the lights–I’m asleep.

On top of the ocean a skinny sandbar emerges, drenched

in purple fumes like fish hair

then the sun disappears: thousands of small chinese dragons

blow tunes on cylindrical fans of

dark vapor; the vapor escapes, filling up

the left-over bits of sky with a color that clings

simultaneously to us oh no! oh no oh blue

I’m covered up and tucked in a little too soon, Father

SUN!

where’s the dark room of the sky before

chaos? First chaos, then us then more of the same us

when we slip into each other.

Thank you I knew you’d be back I knew you were there

all the time; in fact, I saw you licking under the moon’s ass

I saw her swell up with delight and fall on top.

The lights went off and Bernie, Rachel and Leona came from the kitchen with rice,vegetables and the bread. Gerry passed a large chalice filled with the wine he had found in a cupboard. Each one sipped and passed it. They held hands. The food came around. Everyone chewed slowly.

Suddenly a bright flourescent light came on in the kitchen. Parker Wainwright stood in the doorway with his wife. Peter got up to greet him, but he said, “Please don’t move. This is the way the place should be used. If only some of the young people who belong to this church had your spirit. I wish you would stay here awhile and talk to them.” Mrs. Wainwright smiled. Peter invited them to join the meal, but they had already eaten, the minister said. He would be back in the morning to see what they wanted to do next.

After the meal was over, Peter asked Leona to take a walk. As they passed through the arcade and out into the parking lot, she said, “I hate to miss work tomorrow. My tenth graders are doing a scene from Romeo and Juliet and my boss is just looking for things to count against me.

He said, “I know it’s hard to be absent, but can we focus on where we are right now? Isn’t it incredible after the crash and the eclipse and blowing up the engine to find ourselves taking sanctuary in a church? Doesn’t it seem like we’re being guided?”

They were passing under the steeple tower and around to the front of the main building, where they could overlook the valley below. Leona said, “Well we’ve developed quite a group sense after all these crises.”

“Exactly,” shouted Peter, cutting her off. “This could be a new beginning, the moment of conception. We can’t just let it go by.”

Leona stopped walking and rubbed the back of her neck with both hands. “What do you mean?” she said. “Are you still stoned?”

He moved behind her, put his hands over hers and massaged her neck, trying to undo the injury. “No I’m sober. That minister said stay here as long as you want to. Maybe we need to do that, just be open and wait. Let our future take control. Sometime you’ve got to take a blind leap. You decide in the blink of an eye, and then reality appears completely different.”

They were looking at the car lights down on the turnpike. Leona said, “Peter, you know I want to make a new start too. But do you have enough confidence in this situation, in these people, to make the leap now?”

“We have to plant the crystal sometime. But I need you as a partner. We could do it together,” he said.

“I don’t know,” she said. She moved his hands from her neck. “That’s not helping. It’s cold. I want to head back.” As they walked through the parking lot, she added, “Let’s see what the others have to say.”

Bernie spoke first at the meeting Peter called. They were sitting in a circle by the fire. “I dont know how long it’ll take to fix my engine, probably a few days at least, if it can be fixed and if I can get the money.”

Ron said, “I have to get back in time for work on Tuesday. I’m already going to miss my classes tomorrow. I’ve got a low number in the lottery and if I don’t get into law school, the draft board is going to be after my ass.”

Kent said, “Well, I’m ready to quit school. Except for Peter’s course, last semester was a disaster. I just can’t concentrate and I don’t care about playing the game any more. It wouldn’t be hard for me to get a 4F deferment.”

There was a pause. Annie got up and walked to the middle of the circle. For a while she said nothing and moved from person to person with a questioning stare. Then she began. “I think we should just stay here like the minister said. Why go back? We’ve finally cut loose.

“Stay here doing what,” said Ariel, “What are you talking about?”

Annie replied, “Maybe get jobs in Pawtucket.” She exaggerated the length of the first syllable and her eyes twinkled as they landed on Peter’s. “Maybe find a big old house with a barn and cats and some land right here. I bet the rent’s next to nothing. Maybe teach Sunday school at the church.” She had the voice of his angel, but was she only teasing?

Then Ramon spoke up, “Well, you guys may be willing to throw it all away, but I’m an artist and I’m going to make it big in the city, so count me out.”

Bernie said, “Rachel and I want to settle down somewhere in the country, in some kind of commune. This minister is being nice to us, but when his congregation sees us, or for that matter, if we stayed around here and any of these people in Rhode Island saw us, they’d run us out of town. Plus all this religious stuff turns me off. I just want to grow vegetables. I’d sure like this group to hang together, though. What do you think, Peter.”

Peter felt trapped. The magic wasn’t effective enough. Faith was strongest in those who depended on him. The ones that he would depend upon were dubious. Should he try to bring them around as he’d tried with Leona? He trusted her. It didn’t work. If it did work, could he trust them?

Finally he started talking just to see what he would say. “This has been a big experience. We’ve become a fellowship. We’ve been rescued three times. We’ve witnessed wonders. Maybe we could work wonders. It’s been done. Do we really want to?”

Noone spoke. He looked at Leona. She was watching the fire. The bell in the tower struck.

Peter said, “Well then, it looks to me like we’re going back to the city tomorrow. If the VW doesn’t recover, a one-way van doesn’t rent for that much. We haven’t escaped, but this could be a beginning. Spring’s coming. We can go on more trips, camping, exploring, shopping for alternatives. There’s lots out there. Let’s see who comes along.”

By four o’clock Monday afternoon, he had delivered the Ryder rental van to the depot in the East Bronx. On the long busride back to Manhattan’s upper West Side, Peter felt suffocated by the dense veil of urban reality. How could he look at these garish signs for pawnshops, peepshows, liquor and drugstores cluttering the facades of crumbling buildings topped with thickets of TV antennas? How could he bear these stoop-shouldered heavy-shoed people with their hands in their pockets shuffling through streets congested with traffic? How could he return to this hell on graveyard shift tonight? “It could have been all over, if only…,” he said to himself, “but at least there’s someone at home to wait for me.”

Leona said “Hi,” from the kitchen when Peter came in the door. He didn’t answer, but took off his jacket and boots and sat down in a half lotus position on the carpet, trying to stabilize his mood by centering himself in the symmetrical pattern. Leona walked into the room carrying a bowl of uncooked rice she was about to boil and set it on the low shelf holding the candle and the carved hand of Buddha. She bent down next to him.

The stroke of her fingers in his hair brought tears to his eyes. “You let me down,” he said.

She moved to face him. “What do you mean, I let you down?” The color had drained from her cheeks. “If you want to be their teacher and their guru and their camp counsellor and their stud, I’m not standing in your way. All you have to do is believe in yourself. Beth believes in you. So does Kent. Just go ahead.”

Her words were swords. Peter tried to block them by chanting to himself and concentrating on the pains in his knees.

She continued, “But you won’t, not when you’re sober at least. Because one part of you knows your influence depends on drugs and sexual fantasy. Go ahead, sleep with Ginnie and Beth and Ariel and Annie, like you’ve told me you want to. Separately or all at once. Or maybe you already have, for all I know what goes on here while I’m at work. Go ahead, keep blowing your brains out to turn them on. I cant stop you.”

Peter pressed his hands to his ears, but it didn’t help.

“You said you needed me. For what? To be your disciple when you’re high and your therapist when you’re on a bummer? To give you the sexual confidence to seduce other women? To get them for you? I wont be your wife, so that you can have concubines. I want to be your partner, but not your assistant. I also want you to take care of me, when I’m down or sick or injured.” She rubbed her neck. “I married you for some strength.”

Peter’s head bent forward and his elbows sank to his chest. To pull his hands from over his ears, she took hold of his wrists and dug in her nails.

The physical pain set him off like a fuse. He grabbed her wrists and pushed her backwards down on the carpet, pouncing on top of her and forcing her hands to the floor. It was easy, her wrists were so fine. He was afraid he’d really hurt her, especially with this whiplash. But he couldn’t stand listening to any more. She frustrated him. He hated her.

She pushed and raised her left wrist partly off the ground, so that both of their arms trembled. He could sense the adrenalin giving her a surge of strength he had seen once before when a cop clubbed a student in Fayerweather Hall and she pulled a phone booth out of the wall and pushed it down the stairs at the crowd of police in riot gear. With a quick move of her hip, she threw him off balance to the left, and tumbled him over, holding him down with the full weight of her knee on his chest.

He couldn’t believe this was happening. The fire in her eye, the flash of her teeth, the gasps of her breathing. He laughed with surprise and exhilaration.

“Shut up,” she shouted, and he felt his own strength increase. He brought up his knee behind her and pushed her forward onto his chest. He clasped his arms around her back and pressed her tightly against him, straddling her calves with his feet. She squirmed, and coupled they rolled on their sides lengthwise on the carpet. They both felt the stir in their loins and their grimaces melted into laughter.

After their lovemaking they sat abstracted and alert. Leona’s neck, no longer askew, lifted the column of her spine. Her full breasts curved upward. Peter’s strong chin jutted out. His back arched. He placed the wooden bowl of rice between them. With his right hand, he scooped a portion and held it out in front of him. Leona extended her cupped left hand and slowly a stream of grains poured into it, the excess spilling onto the carpet. She raised her left hand and released a stream into his cupped left hand waiting below. They repeated the game until the grains were all on the carpet, spread in a random array. Then, just to slow the time, they began gathering and arranging them over one of the designs in the rug, the flaming Phoenix. When all the grains were gathered, the new design was complete: a round-topped oblong contained like a flower in a tear-shaped vase.

Leona asked what he thought it meant.

“Generation,” he said. “The outcome.”

“Are you ready for that now?” she said. “I’d like to get off the pill.”

Peter felt something moving under him. “Yes,” he replied. “So would I.”

December 1974, November 1992