Terry Tempest Williams

Friday November 17 enroute Salt Lake City to L.A.

Last night Terry Tempest Williams spoke and read at the Wood River Presbyterian Church. The day I arrived in Ketchum, when I saw this event announced in the paper I’d bought tickets for me Joe and Amy to attend on our last night. The large parking lot was full, the sanctuary of the church, which houses Ethan’s preschool, is a large wood panelled cavern with side windows giving on a view of the dashing river just outside. I’d read Williams’ canonical ecoliterary text, Refuge, years ago and essays in Orion along with her collection, On the Open Space of Democracy. Eloquent and informative, her writing is driven by urgent personal grievings and celebrations, by the need to formulate dilemmas without resolving them, and by an activist’s unrelenting drive to battle for what she believes in. I would have gone out of my way to hear her speak in California, and yet here she was at the doorstep of our home away from home.

On the way into the hall, Joe and Amy introduced me to people of many ages they knew. I was glad to have nudged them in the direction of folks interested in writing and ecology among their own extended circle of neighbors, especially after talks about Amy’s community involvement on the board of directors of Ethan’s school and her strong opinions about the error of demanding twenty percent rather than fifteen percent from developers to create affordable housing.

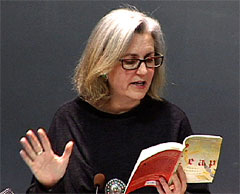

Terry was introduced by a young woman who sat on the Ketchum Arts Center board that sponsored her talk in connection with a display of photographs on the theme of nature and place that I wished I had known about. The bad setup of the p.a. system made her hard to understand, and for the first part of the program I was irritated to the point of distraction that in such lavish surroundings and at such a pricey occasion, nobody was taking responsbility for the sound. Terry took the stage, and with an apology for shakiness due to diarrhea from food poisoning, sat down to deliver her presentation. I was surprised by her appearance, for some reason expecting a dowdyish presence from the Mormon wife of a contractor, but instead finding a svelte, blackbooted, silverhaired beauty.

Terry was introduced by a young woman who sat on the Ketchum Arts Center board that sponsored her talk in connection with a display of photographs on the theme of nature and place that I wished I had known about. The bad setup of the p.a. system made her hard to understand, and for the first part of the program I was irritated to the point of distraction that in such lavish surroundings and at such a pricey occasion, nobody was taking responsbility for the sound. Terry took the stage, and with an apology for shakiness due to diarrhea from food poisoning, sat down to deliver her presentation. I was surprised by her appearance, for some reason expecting a dowdyish presence from the Mormon wife of a contractor, but instead finding a svelte, blackbooted, silverhaired beauty.

Cupping my ears with both hands, I tried with limited success to follow what she was saying. She spoke about her own long history in Sun Valley”coming here by train every summer vacation as a child and later having a spooky experience staying overnight in the Hemingway house while attending a writers’ conference. She commented briefly on stuff in the local paper–efforts to deal with the lack of affordable housing and problems of land use”and then on some of her efforts to preserve wilderness areas, going to testify before Congress, and being snubbed both by her Senator”the smug and sinister Orrin Hatch”and Republican representatives on congressional natural resource committees. She told of organizing a dozen eminent writers to provide heartfelt testimony for wilderness preservation, arranging funding to collect their essays in a book, getting it all accomplished for no money within a few weeks, and the fruitlessness of those efforts in a Washington dominated by lobbyists and corrupt politicians.

As she moved on to more personal reflections, alternating between fluent cross-legged conversation and reading from written work, I got up and moved to the back of the room where I could her muffled voice a little better. Her recurrent mantra was a quote, I think from Geoffrey Bateson: the earth will not be mocked, God will not be mocked. It was about the harm we do the land and its resources and the inevitablity of paying the price, harvesting the consequences. She mentioned her present project, called Mosaic, a book about gathering broken fragments and giving them some kind of meaning and form. The grief for what we are destroying, the combined fear and welcome of retribution for those crimes, and the effort at some kind of ritualistic compensation to placate angry natural forces struck a chord in me. It reminded me again of the pulpmill graveyard shift poems in my winter pastoral which I’ve been thinking about adding to my weblog. She read a poem grieving the death of her brother from lymphoma at age 47”an account of making a totemic memorial for him and building a bridge of stones across a creek. Then by association of grief, stones and bones, she segueyed into a reading from her work in progress”an account of a recent visit to Rwanda with a friend who was in charge of constructing a memorial to the genocide victims of the 1990’s. She told us this would be a twenty minute piece, both as a warning and as a promise that it would be over. Remembering the agony of watching Hotel Rwanda, I felt bad about inflicting an ordeal like this on Joe and Amy in the guise of an evening out on the town.

The trepidation was well founded. The descriptions of what she saw”the churches full of bones, the mobs of orphans, the ravaged landscapes”and of the events twelve years earlier that created these remnants”inflicted pain. They were vivid, full of expressions of her own grief and inadequacy, yet unmannered and unsentimental. Having to strain to decipher the fuzzy voice amplified the effect”the story too horrific to be clearly articulated. In the middle of her reading she looked up from the typscript, gazed sympathetically at the audience and said “ten more minutes.” The last part of the narrative was less gruesome than the first, full of stories of children dancing and singing and laughing, of generous donations of labor and materials for the memorial by Chinese contractors, and of admiration for the courage and determination of her local guides. But when she concluded, the audience was silent for several seconds, and then applauded and then stood applauding, shaken as she was, in the light of what we all knew about today’s genocide in Sudan and Chad.

After a few questions, one of which led her to mention that both Tutsis and Hutus in Rwanda were 98 percent Christians, the presentation ended with a reminder that she was not well. Nevertheless I joined the few people surrounding her to get books signed to tell her how her Open Space of Democracy, had inspired our Sierra Club chapter chair, Karen Merriam, to change the emphasis of our political mission from confrontation to consensus building activities that have brought us into coalition with traditional opponents, the Chamber of Commerce, the banks and the power company. I knew that this bit of feedback would reward her staying another couple of minutes, but I didn’t expect what I got: she looked at me deep in the eyes, smiled and said I had made her day. As I backed away abashed, she stepped after me, put her arms around me and pressed her cheek to mine.

I walked out of the sanctuary on rubbery legs, head clouded, face hot. Thank you Karen.

The morning after, on my way to the airport with Joe, I remembered the last time I experienced a burst like that: it was two years ago after the hug and kiss I got from Doris Haddock, the woman who wrote her first book about the walk she took across America at age 90 to agitate for campaign finance reform.