Columbia 68 and the World (2)

Ten days after it ended, I’m still processing the conference and slowly going through my notes trying to sift out memories and lessons to keep. So much of significance was happening at every moment that weekend–the recreation of past occurrences forgotten or newly understood, the simultaneous evocation of forty years of experience in hundreds of exceptionally conscious minds, the unfolding of present day history in encounters with young people and emergent political disputes, plus the emotional impact of connecting with old friends–it could generate a different book by every one of the participants. I look forward to see what comes of the many films, sound recordings and pictures documenting the activities while they were happening. This picture was taken on the front steps of Peter Behr’s family home in Middle Village Queens, where we stayed for four nights during the conference. I had spent the whole ten hours of our flight engrossed in the story of the strike narrated in the 300 page book, Up Against the Ivy Wall, written immediately after it concluded over the summer of 1968 by the student reporters of the Columbia Spectator. I hadn’t looked at the book since the year it was published, and clumps of its pages came apart as I read. I was astounded by the precision of its research, the astuteness of its political analysis”even with the distance of hindsight–and the liveliness of the narration. As I finished with each clump of pages I passed it to Jan who was equally enthralled. The book was edited by Robert Friedman, Spectator‘s editor at the time and now one of the organizers of the conference and moderator at many of the sessions.

We arrived at Newark airport late Wednesday night and traveled by airport monorail to the transfer station where we were picked up by the hotel shuttle and taken to Howard Johnson Inn nearby. At that hour the driver, passengers and hotel clerk were Africans, widely varying in feature with different hard-to-decipher accents, all extraordinarily good looking and coal black. I couldnt resist staring. Once again, it was brought home to me how restricted is the circle of people I encounter in my three different homes, San Luis Obispo, Lund B.C., and Ketchum, Idaho. In the morning we took shuttle, New Jersey Transit railroad and the E train Subway to Queens. I marveled at the varieties of public transportation, its speed and efficiency and the luxury of being able to do nothing but look at the the rich flow of faces while in transit. Peter picked us up at the Forest Hills station and gave us a tour of his childhood haunts. At his mother’s house, two local women he’d hired were painstakingly cleaning the filthy kitchen and schmoozing nonstop with New York accents straight out of Archie Bunker. The place was awash in clutter and disrepair, but he had arranged for one upstairs bedroom to be clear enough for us to inhabit comfortably. The two other bedrooms were packed with bags, boxes and trunks of documents. Jan started in sorting them and trying to build a picture of Peter’s mother’s financial and legal position. Before the men in the white coats came and took her to the hospital and Peter transferred her to a nursing home for the demented, she had kept all the papers but deliberately confused any order so as to foil the interlopers she feared would find them. Peter assigned me the job of matching the pile of keys to the more than a dozen locks installed on the house’s doors inside and out. One was a foot and a half off the ground on the outside of the basement bathroom. Peter said she feared the neighbors coming in that way. In the late afternoon Peter drove us across the Triborough Bridge through Harlem to Morningside Heights, passing the building on 110th st. that he and Linda lived in when she was kicked out of Barnard. The neighborhood had been frightening in those days”someone was killed in their apartment building’s lobby”but now was gentrified. Across the street the huge mass of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine was blocked from view by a high-rise condominium on the church property. We picked up Linda Grace at the corner of Broadway and 94 St., the four of us together for the first time since their breakup in 1969. We’d met at a draft resisters’ picnic in Riverside park shortly after Jan and I moved to New York from California in 1967, and we’d shared many adventures in addition to the Columbia strike, including frequent stays at the Total Loss Farm commune in Vermont and a road trip through New England to Quebec.

We found a parking spot on 112 st. and while searching for a place for dinner I picked up a copy of the current Columbia Spectator.The whole issue was devoted to the conference we came for.

We ended up at the West End Bar, now part of a chain renamed Havana Central, but still featuring a menu recalling its history as a home of beat generation writers and sixties radicals.

While waiting for our order I opened the Spectator to a full-page story about the saga of Peter and Linda.

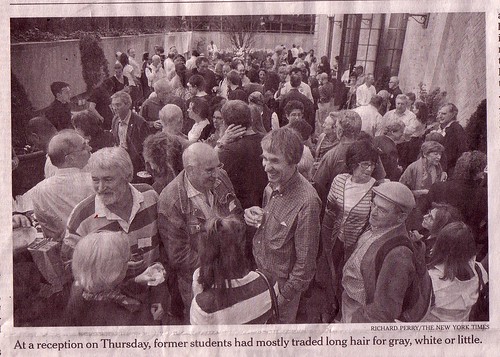

After a better dinner than any served in the old West End, we crossed College Walk to Casa Italiana, where a crowd waited to get in to the oversubscribed opening reception and panel. Eyes scanned aged flesh searching for traces of the youthful countenance that the mind groped for in shreds of memory. When one of the two connections sparked the other, arms embraced. Although I knew none of them, it was gratifying to observe the number of African-Americans present. At the door stood Stewie Gedal, trussed in earphones and mike, but easy to recognize.

At the well lubricated reception on the back verandah, people packed close and exploded with resurrected moments and contemporary associations. One man said he remembered me moaning in the art school on a Saturday morning during a break in our life drawing class when the model was particularly attractive, “I cant take any more” and heading home to my wife. Another man, married to a former student in the Pastoral and Utopia class, told me he works with a former Cal Poly political ally and friend who now is Provost at Cal State East Bay.

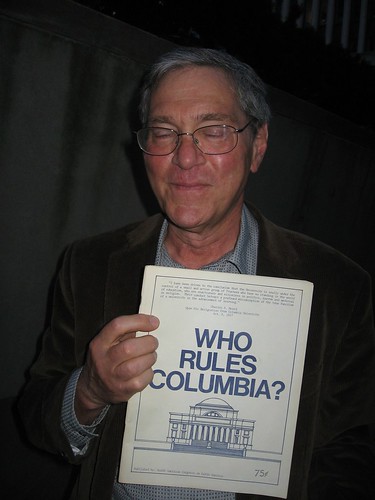

Through the crowd, I pushed my way to Michael Klare, expressed my admiration of his work then and now, and asked him to pose for a photo with my treasured copy of “Who Rules Columbia,” the conclusive indictment of the University produced in 68 with the help of secret documents “liberated” from President Grayson Kirk’s office by the strikers.

Prodding by organizers finally succeeded in herding the obstreperous crowd of several hundred into the Palazzo’s lavish ballroom. Above the podium was inscribed a Latin motto in Columbia’s hallmark font of imposing capitals: MORIBUS ANTIQVIS RES STAT ROMANA VIRISQUE””The Roman state rests upon customs and men of old.”

Built in 1926 and described by one scholar as Fascism’s “veritable home in America¦a schoolhouse for budding Fascist ideologues,” it was hard to decide whether the selection of this venue for the opening event was a joke by the rebels on the University or the other way around. The first speaker was Nancy Biberman, who welcomed the crowd and introduced the members of the conference organizing committee. She began by pointing out that no women belonged to the strike’s leadership group and the only mention of women in the history of the period was the President of Barnard College, Martha Peterson, who overruled her own appointed judicial committee and kicked Linda Leclair out of school for living with her boyfriend. Linda and Peter stood arm in arm at the back of the room receiving wild applause.

Nancy affirmed that this marginalization of females to food preparation and cleanup roles during the strike led directly to the foundation of the 1970’s feminist movement. Her own history as founder and CEO of the Women’s Housing and Development Corporation exemplified the success of that movement and also the way that so many participants in this reunion had stayed true to the convictions of forty years ago.

Nancy went on to introduce other members of the organizing committee. First, Tom Hurwitz, whom I could picture from old with a red bandana cutting an Errol Flynn figure of noble pirate. Since then he has become one of the country’s best documentary cinematographers and a verger at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. Next Hilton Obenzinger, community activist, Stanford professor, prolific poet, novelist, essayist and author of the just published Busy Dying, a memoir centered on the Columbia strike. Then Laura Pinsky, counselor, public health activist and author of The Essential AIDS Fact Book. Then Thulani Davis, author, musician, journalist and Buddhist leader. And finally, Robert Friedman, whom I remembered as the trenchcoated and detached student editor of the Spectator in 68, and who in the meantime has been editor of the Village Voice. Robert hatched the idea for this conference with Lee Bollinger, current Columbia President.

In her opening remarks Nancy emphasized the theme of reconciliation. Contrary to the claims of some faculty, administrators, media commentators and later historians, the 68 strikers were not out to destroy the university but to improve it by successfully opposing bad policies affecting race relations, involvement in military research and authoritarian university governance. The decline of Columbia’s finances and fortunes following the strike was due to the decline of New York City overall, its abandonment by the Federal Government. Its later ascendance in the 1980’s likewise could be attributed to the city’s renaissance and growing real estate values. Nancy insisted on the value of the education the University offered both through regular classes conducted by its illustrious faculty and through the strike itself, which provided an experience in real community and in the empowerment of people working together to change what seems like an unalterable and tyrannical establishment. She also expressed appreciation for the faculty’s role during the strike, their adherence to the “doctrine of interposition,” whereby they sided neither with strikers nor the administration but placed their bodies on the line in an effort to protect strikers from conservative students and the police.

This last point struck me as somewhat revisionary in light of what I remembered that drove me to join the students: the faculty’s ineffectiveness resulting from their hesitancy to take sides or split into factions. But it was of a piece with her introduction of the present University president. Bollinger, Nancy said, arrived at Columbia in Fall 1968 and although he didn’t take part in the protests, became a distinguished First Amendment Scholar who authored a book entitled The Tolerant Society and argued Affirmative Action cases before the Supreme Court. Nancy thanked Bollinger for welcoming the strikers back to the University though he emphasized that this was not to be construed as Columbia’s official sponsorship of the conference. At that moment there was an outburst from the audience at the back of the room and both black and white individuals who were veterans of 1968 denounced Bollinger for Columbia’s present day policies involving the development of a huge campus expansion into Harlem north of 125th St.–one that will displace residents and lead to the gentrification that destroys low-rent and largely non-white neighborhoods. I had read a little about this long-standing controversy on the preconference listserv, where it was made clear that the conference organizers both wanted and did not want to be associated with Bollinger, just as he both wanted and didn’t want to make this an official Columbia event, since those who did not agree with the strikers at the time and other conservative alumni were outraged by any such University celebration.

It was becoming clear that the mission of reconciliation would remain in tension with that of continuing struggle. After waiting for the protestors to finish, Bollinger welcomed the overflow crowd and expressed appreciation for the chance to work with the organizing group. “I thought about making my office available to you all night,” he joked and Peter Behr shouted, “Do you have good cigars?” Addressing the evening’s topic, “Columbia 68 and the World,” Bollinger mentioned the convergence of an extraordinary number of things that had to be changed at the time and that young people cared deeply about: Vietnam, Civil Rights, rights more generally, and the environment. These concerns he stated “go to the core of the world we live in today.” This I took as an acknowledgment from one who wasn’t involved at the time, that what we and the other activists of our generation accomplished was significant enough to be honored. One of the outcomes, he stated, was a new relationship between the University and Harlem that has led to a five year process producing agreement on the Manhattanville redevelopment plan. This prompted a new outburst, understandable to be sure, but I, and I think most audience members were relieved when Hurwitz moved in and somehow quietly managed to convince the interrupters to complete their remarks and leave. Bollinger went on to address another recurrent theme”that today’s students have not mobilized in comparable ways and that the current atmosphere is no longer conducive to advances like affirmative action. Nevertheless, he said, students today are engaged in different ways.

Bollinger left to polite applause, and then Robert Friedman took the podium and offered a brief chronology of events leading to the takeover and asked members of a panel of speakers to place that event in historical context. First was Tom Hayden, Thomas Jefferson of the New Left, author of Port Huron Statement, the founding manifesto of SDS. In 1965, he’d been working as a community organizer in Newark, but as the Vietnam war escalated and black power increased, he worked for Bobby Kennedy, getting up every day and thinking of the war.

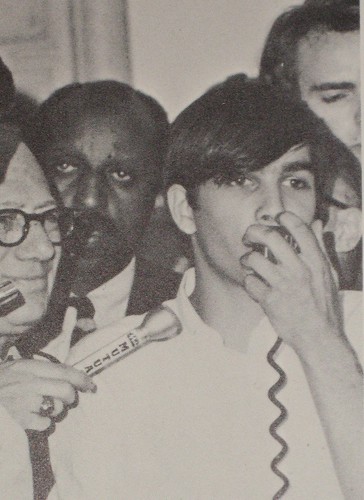

When a call came to him about the strike, he hurried to Columbia and helped with the takeover of the Math building. He saw the strike as I did at the time–a way to show resistance to the atrocity of the war and to put pressure on a local high-profile organization, since there was no way to put enough pressure directly on the federal government to make it respond. Hayden asserted that the takeover of the buildings was a rational tactic of the powerless, taking issue with an op-ed column in the previous day’s New York Times stating that the occupation was crazy, an expression of the madness that arose from the chaotic circumstances of that year, written by Paul Auster, another of the conference’s participants. Next speaker was Bill Sales, head of Ethnic Studies at Seton Hall University and author of the book From Civil Rights to Black Liberation. Bill had been one of the leaders of the Student Afro-American Society which asked white students to leave Hamilton Hall the first night of the occupation and to take over their own building. Bill talked about the alliance established between the Harlem Community and the African American students, many of whom were the first in their families to attend college and who felt alienated from the formerly all white University. This was the period during which whites were being purged from Civil Rights organizations in favor of Black Power. The construction of the gym in Morningside Park with its tiny portion and back door on the bottom floor for Harlem was an affront that Blacks had been fighting for years. Community members supported them with food, political pressure and the threat of massive social rebellion. The black students were taking immense risks by siding with the community against the University, and they came to the conclusion that whites were neither well enough disciplined and organized nor seriously enough committed to be worked with closely under those conditions. “We had to write ourselves into history,” he concluded.

Two other speakers, sitting in for Kathleen Cleaver and Nicolas von Hoffman who made late cancellations, spoke of the ferment throughout the country and the world, not only among students, but among labor unions, women’s groups and nationalist groups rebelling against rulers in both Communist and capitalist societies. Someone stated that 1968 began as a year of great promise, with Lyndon Johnson’s refusal to run for a second term, the Prague Spring and the success of the Columbia strike, but by the end of that year, with Nixon’s election, the crushing of the Velvet revolution in Czechoslovakia, the killings at Kent State, and the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy, hope had waned. Bill Sales countered that for Black people, Columbia 1968 ushered in a decade of great progress: the militant takeovers of Cornell and San Francisco State for instance, which led to the creation of Ethnic Studies programs nationwide, large increases in college enrollments of minority students, and hiring of faculty of color. He pointed out that though many books and films had told the white students’ story, that of the Blacks had yet to be told, but in fact was now being completed by a PhD candidate at Columbia in the audience, Stefan Bradley. It was clear from Thulani Davis’ participation in the planning, from Sales’ presence on the panel and from the turnout of African Americans in the audience that this story, like that of the women’s role in the strike would be surfacing at the conference for the first time. As the evening lengthened and the load of impressions grew heavier, my note taking got more disjointed. And now, as the number of days since the event grows, my memory of specifics frays.

Friedman’s questions led the panelists from recalling the past to reflecting on the present and predicting the future. Hayden noted the importance of keeping the memory of Columbia 68 alive as encouragement to those fighting against war, racism and injustice now. It was the triumph of a youthful, idealistic perspective that refused to accept the cold-war, materialistic, ethnocentric, corporate worldview promulgated by the media and by most authority. Today that dominant culture is even more monolithic and pervasive, and it seeks to erase the memory. He mentioned also that he is the father of a recent college graduate whose enthusiasm for Barack Obama echoes the hopes of 40 years ago and who has convinced him to see the connection between them in the present campaign. A member of the audience claimed that Columbia is more dangerous today for Harlem than it was in 68, not only in process of destroying one of its neighborhoods, but also planning to install a biological warfare laboratory deep underground as part of the new facility. She stated the obligation of those gathered to attend a protest rally and march of the West Harlem Coalition coming to the campus on Saturday.

All speakers shared the affirmation that we must not allow this anniversary to remain a celebration of past glory but to make 68 alive now and in the challenging future of the world and our own aging. To counter any weariness prompted by such resolve, Bill Sales told of his recent meeting with John Hope Franklin, 94 years old, dean of African-American historians, former President of the American Historical Association and political activist to this day. “I looked at him like a walking tree under which I could get shade.”

Note: To access more photos, a slideshow and larger versions of the ones included here, go to this flickrpage.