The History of Peas

It started with the financial meltdown last September. I hired Chris to help me take down the ziggurat I’d constructed 7 years ago at the top of the hill and use the railroad ties to enlarge the vegetable beds. They were soon filled with spinach, chard, kale and lettuce and I began hankering for more territory to plant.

In early November I went up Stenner Creek Road with Lucas and loaded our Subaru, Jade, with serpentinite boulders I found abandoned at a turnout. I dug up a dozen heavy carex clumps in front of the house and transplanted them to make a little retaining wall, spaded and levelled the adobe clay in an irregular eight by five foot patch that might catch a little winter sun, laid out a new path around part of it connecting the brick walk to the top trail, surrounded it with the boulders, and worked in leftover compost.

I decided to plant sugar snap peas since, like the leaf crops, peas would grow in winter on our north-facing, shaded slope. Peas also enrich the soil and grow large plants in small patches of ground. Like tomatos, their expansive vines provide something to watch and fiddle with, and they yield an ongoing harvest of food that’s good raw or cooked, both the pods and the little treasures inside.

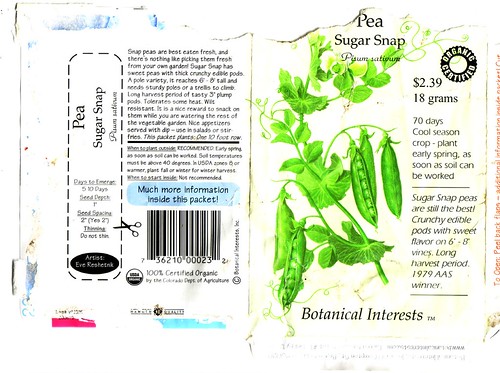

I couldn’t find organic sugar snap pea seeds anywhere in town in November, but New Frontiers put in a special order. The packet was embellished with an an enticing illustration and invitation:

Once torn open it also offered information about the history and culture of the fruit.

I’ve always been a little intimidated by gardening, partly because I could never compete with my neighbors, Stan and Peter, back in the seventies, but also because of the patience required by its slow rhythm and its uncertainty of outcome. With both anticipation and fear, I patted the little off-white marbles into the holes I’d punched with my fingers every two inches into the dampened soil. After just a week of watering the seedlings came up juicy and vigorous and curled their tendrils around the fence marking the row. I’d gotten the thumbs up from the Great Outdoors, confirmed every morning as I watched their progress in the golden light of sunrise.

In the space enclosed by the fence, I’d planted spinach, beets and chard, which I knew could get enough sun while the peas were short but that could thrive in the shade as the vines grew higher. By the first of the year the vines required taller supports and I wired together pairs of bamboo stems from the backyard and made crossing arches by sticking both ends into the soft but solid clay soil.

By the end of January the thick growing tips had started sprouting shafts, each carrying two buds, along with wrapped and wrinkled miniature leaves. Then the buds burst into translucent white flowers of pleasing and suggestive shape. The stems reaching upward were thick as a pencil, hollow, delicate and brittle.

The night of February 1, the wind howled and I tossed in bed worrying that they’d be bruised and snapped. In the morning my fears were confirmed. At least ten of the stalks were cruelly mangled. I found a ball of soft cotton thread and gently splinted them to fence and bamboo stalks, hoping that like other plants they might compartmentalize the wounds and grow around them.

And so they did. Meanwhile the blossoms dried and shrank as the seedpods at their bases swelled from the sepals. I exulted with the sensation of reciprocated love, less eager to devour the fruit than to glory at the plants’ continuing climb.

Having run out of old bamboo stalks, I remembered a runaway patch of living bamboo pushing through the asphalt in the alley off Longview Drive just two blocks away. I drove over and cut a dozen ten-foot tough and flexible stems and wired them into eight foot tall arches. They dug easily into the ground and wove a structure that reminded me of the willow domes built by the local Chumash.

As the vines climbed ever higher, sprouting clouds of blossoms on their way, the pods on the lower tiers began to fatten. I found that they reached their zenith of succulence as soon as a hollow pucker developed at the connection to the collar of sepals.

Now the harvesting began. First just a few individual pea pods reserved for Lucas and Ian, with the occasional snack allowed to Claire and Jan.

But no limit to the numbers I needed to test as I hunted them down in the dense forest of vines. Then the pods ripened in larger bunches that required harvesting into plastic bags every few days

I sent one with Jan as largesse to share with her book group, and gave others to neighbors on the block and folks at the Sierra Club office, anticipating the moment when their faces lighted with surprise as they bit into the tender crunchy morsels that exploded with flavor and melted in their mouths.

As the vines reached near the top of the third tier of arches, I recalled Jack and the beanstalk while I climbed on a stool to secure them with string. Entering the enclosure they made, careful not to step on the ripening spinach and beets, I felt enclosed in a sacred canopy like a succah or a hupah.

By the end of the first week of the quarter at the beginning of April”my first time teaching in a year”I harvested a bag large enough to share with my freshman Argumentative Writing class while we read Michael Pollan’s proposal for reforming the American food system, “Open Letter to the Next Farmer-in-Chief.” The essay ends by urging the President to rip out a section of the White House lawn and start a Victory garden to set an example of how individuals can participate in food production, reduce global warming, improve their health and have fun. I showed pictures and mentioned that reading that essay had influenced me to plant the seeds.

The week before Easter, sensing that the giveaways were getting tiresome, I started blanching the harvested peas and storing them in half pound bags in the freezer. As long as I could still eat my fill raw, they were too precious to cook.

At about the same time, the plants stopped growing higher and started to brown near the bottom. Those that had been cracked by the wind, yellowed altogether. I left the longest and fattest pods on the vine past the moment for optimum harvest and marked them with string to save later for seed.

During Easter week, I felt the urge to plant new crops that would ripen in summer and bring back variety and mystery to my farming. I got irritated with the peas for taking up so much of the little room I had in the sun and for casting too much shade. I searched for vines that were no longer producing that I could cut to liberate space for big tomato transplants and seedlings of squash, pepper and cucumber. When I realized I was killing pea vines that were still producing flowers and would continue to yield, I felt shamed and disloyal, and I dug up more carex and pulled out two mature Toyon bushes to extend the growing ground.

To be continued