Bonding with Beethoven (6)

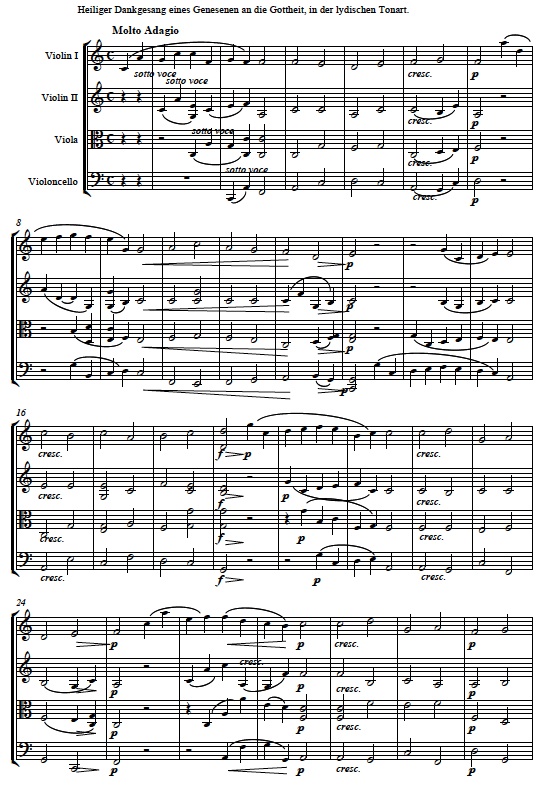

I˜m ready to move on to another late quartet. On the drive to pick up Ian from school in A.G. I listen to Opus 132, quartet #15. The third movement Adagio is unlike anything I’ve ever heard. The exaggeratedly slow opening tempo that slows even further, the notes’ uniformity of length, and the alien sequence of low pitches add up to what seems like several minutes of formless, unconnected sounds. They’re followed by a wild flurry of ecstatic dance music, then a slightly more active modification of the slow section, then another exultant interlude, and a finally a complicated set of variations of the opening that combine both slow and fast sections. Beethoven called this “Heiliger Dankgesang eines Genesen an die Gottheit,” A Convalescent’s Holy Song of Gratitude to the Divine.

My reading reveals that though I’d never heard of it, this piece is one of Beethoven’s greatest hits. Produced while he was suffering from a combination of painful abdominal ailments from which he feared he wouldn’t recover, he wrote to his doctor afterwards that the notes helped to cure him. I listen to an online lecture by musicologist and composer Jeffrey Kapilow to an audience at the Stanford Medical School that provides a lucid and enthusiastic explication of the piece’s unique structure and style. I can follow the lecture the third time around with the score in front of me, except for the part about the last little section. Sitting in front of the shrine in my study that contains my parents’ cremated remains, I imagine the opening preludes and chorales as two alternating voices: one invoking the dead the other their replies.

audio [opens in new window]

You who came before us now speak

Here still at rest we stay and watch

Comforting, you offer witness

Life no longer can disturb us

Lying, sitting standing you gaze

And our repose remains complete

Held in effortless suspension

At last we know our final state

May you grant us understanding

All we can pass to you is love.