London July 29

An unenterprising morning following yesterday’s varied activities preceded the familiar busride back to the West End where we’d planned again to be royally entertained in the theatre, this time at a performance of The Book of Mormon, the acclaimed musical I’d been eager to see since its first appearance in New York in 2011, where it’s still running. Knowing that its satire, written by the merciless creators of South Park, targeted the Church of Latter Day Saints, added to the anticipation resulting from my ever-increasing aversion for all religious dogma and enthusiasm. Having learned of the Mormon’s Church’s strange beliefs and violent history from John Krakauer’s Under the Banner of Heaven, I was ready for some naughty fun.

I wasnt disappointed. From the golden statue of the Angel Monroni at the top of the proscenium to the lighting, sets, live orchestra, brilliant singing and dancing, the show offered irresistible spectacle. But the audience was most gratified by laughing at the foibles of its American characters blithely unaware of their own personal issues–runaway narcissism, suppressed homosexuality, clinging dependency–offering conversion to Mormonism as a solution for the more serious problems faced by their African hosts: AIDS, female circumcision, child sexual abuse, and oppression by a murderous local warlord.

During intermission, delighted audience members chatted with neighbors. Based on their haircuts and necklaces, Jan correctly surmised that three women in the row in front of us were Catholic nuns. We bonded with them in mockery of that other version of Christianity,

After the matinee, we hurried through the mob of tourists in Leicester square to snatch an hour at the nearby National Gallery before it closed on this last day of our stay in London.

I felt satisfaction at being able to squeeze it in, but regret for not scheduling more time to experience supreme highlights of 700 years of European art. We agreed to limit this pilgrimage to visiting just a few paintings by favorite English masters, Turner and Constable.

I ended up honing in on two.

Turner’s “Dutch Boats in a Gale” captured an infinitesimally brief moment of infinitely complex motion. The flicker of light and shadow, the churn of water and clouds, the press of wind against sails and waves, the torsion of sailors and boats, the race of the viewer’s eye from left to right, foreground to distance, all miraculously frozen.

By contrast to oceanic turmoil, Constable’s “The Cornfield” offered a vision of tranquility anchored in a stable but lively rural scene. Great trees and moving clouds framed a village and church in the background and farmers in a sunny field in the near distance reaping a plentiful summer harvest.

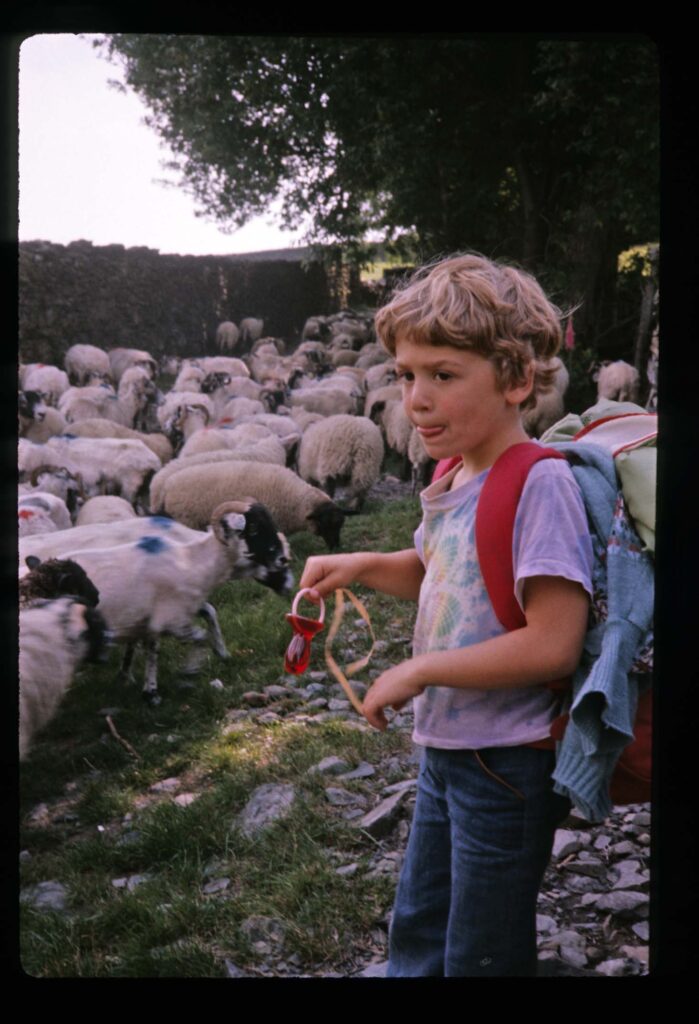

In the foreground a shepherd boy lay on a bank at the edge of a natural fountain slaking his thirst while his border collie attended, looking up at a bird, a guardian donkey and her foal grazed nearby, and the trusting flock of sheep ambled down the road ahead.

The subject matter and feeling of the painting distill the ideals of the pastoral, once again recalling the years of academic work I spent exploring that subject in libraries and in life experiences in Canada and the English Lake District

Ushered out of the museum at closing time into Trafalgar Square, it seemed that the afternoon light transformed the clouds, fountains, Nelson’s column, the church of “St. Martin in the Fields,” and the crowds of people into more paintings.

During an earlier phone call with the boy, now 52 years old, he’d encouraged us to go to the Porcupine, his favorite hangout with college friends during Spring 1992. We found it a few blocks away for a last beer and meal of London pub food.