Japan Trip–Day 2

Light from the rising sun pours into the sixth floor window of our ryokan perched on a steep slope inside the crater of Hakone. Beneath it a ring of peaks is broken by the river valley that opens into the sea. I drink green tea from a cup on a wooden coaster, brewed on the low table next to the futons where we slept and I lay wakeful for a good part of the night, overstimulated with impressions and still not adjusted to the seventeen hours lost by travel across the Pacific. I’m dressed in the elegant cotton yukata I wore to dinner last night and to the hot sulfur baths where I soaked yesterday afternoon and this morning at 5.

Our second day in was largely taken up with bus travel through heavy but smoothly flowing traffic in Tokyo streets and on expressways and tightly curved mountain roads during this Spring Equinox holiday weekend.

The transit time was enlivened by the variety of unfamiliar landscapes and the continuous offerings provided by our beautiful and hard working guide Maya. She lectured on geography, history, linguistics, geology, cuisine and etiquette, using maps, color handouts, flip cards, little cheat sheets, and mnemonic songs. I learned, and immediately forgot, basic greetings, numbers, some written Japanese characters, and a jingle in tribute to Mt Fuji.

After driving for an hour south from Tokyo through a dense urban world”all buildings outside the center appearing recent, angular, drab but clean–we suddenly entered a landscape of forested mountains, river valleys, little villages and artfully bordered rice patties. The brown pre-spring vegetation was offset by patches of evergreen and a few groves of plum blossoms. The expressway rest stop buzzed with vacationers, food vendors and souvenir hawkers.

First destination was Mt. Fuji, which the bus ascended to station 5 at about 7000 feet. This is the busy trailhead for thousands of summer hikers who climb the remaining 5000 feet to the summit, a pilgrimage that Japanese expect to make at least once in a lifetime. We got off the bus and entered the crowd battling the cold wind. Away from the parking lot the ground was covered with snow and ice, but eventually we came upon an observation platform sheltered from the gale where one could get a clear view of the summit, which occasionally appeared from behind a streaming shroud of snow and cloud. Despite the buses and multistory tourist facilities, the place felt like a real and dangerous mountain.

After fifteen minutes we were ushered back on the bus for a ride to the Fuji information center near the northern base. The clearing skies allowed for a classic view of the graceful cone whose shape was familiar to me since early childhood from stamps and world puzzles as the icon of Japan.

It would have been nice to slow down and pay homage for a while, but the wind remained strong, the museum beckoned and the schedule pressed us forward. As the bus headed south, through the windows we caught fleeting glimpses of this huge image of unalterable perfection always changing before our eyes. Maya recited the proverb: watch Fuji for ten minutes and you get a hundred views.

Another stint in the bus brought us to Hakone, to the world of onsen–hot springs–and ryokan–traditional rooms. Still under the spell of the mountain, we opened the door to a space whose first impression was comparably familiar and overwhelming: the austere beauty of unfinished planed lumber framing large panels of wall and small panels of translucent rice paper, the tightly woven tatami mats, hard yet springy to the touch, their moldings of embroidered blue silk, the low black table and cushioned floor seats, all waiting for the hotel porter, who arrived just behind us with a pot of hot tea he placed inside a round laquered box containing ceramic cups, wooden coasters and a coiled towel in a basket. He smiled, bowed, and disappeared, silently sliding the doors and leaving us to partake undistracted in the room’s celebration of squares, rectangles and circles.

After a quiet cup of tea, we changed clothes to prepare for the baths. The protocol was inculcated by the guidebook’s instruction, Maya’s gentle admonitions, and posters on the wall in English as well as Japanese. There are two baths, one on either side of the elevator on the first floor, the red curtained for women, the green for men. The designation alternates daily, marked by the changing of the curtain. Yukatas and slippers supplied in the rooms are worn in the hotel, removed and stowed in the sink area and locker room outside the inner curtain and sliding door leading to the tubs. Passing through them naked, I found a steam-filled chamber, to one side the three foot deep pool into which the mineral water flows continually, to the other a row of booths, each with a shelf holding a dozen or so bottles of shampoo, conditioner, body soaps and lotions in front of a full size mirror.

Several of the booths were occupied by men sitting on low plastic stools, assiduously scrubbing themselves with washcloths and brushes and then rinsing off with the hand-held showers attached to plumbing fixtures on the floor between their legs. I followed their example to get clean before entering the pool, and then stepped into the bath and leaned against the wall near the inlet, where a stream of the extremely hot water from the thermal source mixed with a smaller stream of cold to maintain a tolerable temperature. I enjoyed the familiar sensation of pain and stiffness draining from my joints, especially knuckles and knees, and the occasional change in water temperature resulting from some subterranean valve adjustment.

Fifteen minutes later, I was ready to get out but the men in the booths were still busily scrubbing. After two baths in the deep tub and using the advanced toilet appliance in the Tokyo hotel, I’d already felt unusually clean before entering this chamber. What in the world could these guys be doing? But then I remembered the requirement to leave shoes at the door, the little cloth in the tea set, the damp towel offered with meals and the face masks worn by people on the street, and I realized that citizens of this tightly packed country had reason to make a cult of hygiene.

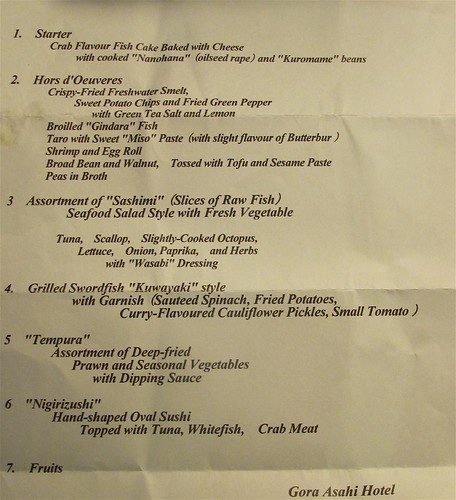

Light-headed after the day’s ascent and immersion, upon entering the banquet room I again felt overwhelmed–this time by the the traditional Japanese dinner panoply spread at my seat. A dozen dishes each of a different shape, color and material held elaborate combinations of artfully processed ingredients. I can picture a small wooden box with a plunger which required me to press a block of green-tea tofu into 20 sharp edged tiny blocks that tumbled into a bowl of misu soup containing scallions and buckwheat noodles, but the rest of the details are lost to memory since I didnt take pictures and neglected to keep the menu. The second night’s dinner was equally complex without repeating any dishes or ingredients:

After this feast we turned down Maya’s invitation to watch a video of “Lost in Translation” and retired to our lodging. During dinner it had been converted from parlor to bedroom, the table moved aside and two futons covering the tatami mats made up with flower-patterned down quilts showing through a large oval window in their fitted sheets.