Slideshow

We took traditional Japanese breakfast with Maya and Anthony on the second floor of the hotel, a decorous and quiet place compared to the busy western style buffet downstairs.

Her lecture on the bus about tea ceremony was a model of clarity and wisdom, the kind of presentation I might have expected from a Dharma talk by a monk. And no wonder, since she told us she has studied it for fifteen years with her 84 year-old teacher, ten before reaching the “entrance” to knowledge. In a composed musical voice with precise articulation she expounded its definition, meanings, history and process, each section marked by a lengthy pregnant pause.

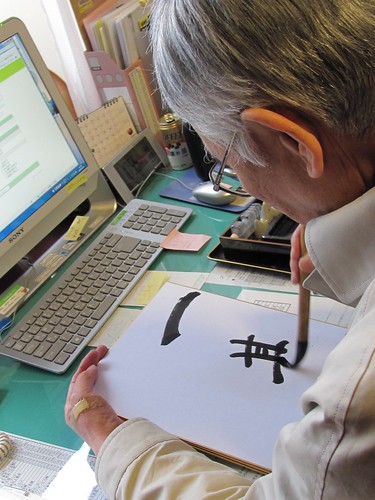

“The Way of Tea,” she said, is a better translation than “tea ceremony.” Tea was originally brought to Japan around 1200 from China by the same monk who introduced Zen Buddhism. Its function was to keep you awake during long hours of practicing Zazen meditation. Both Zazen and the Way of Tea were appropriate to the Samurai way of life. They emphasize the importance of experiencing the present moment, since you can die in battle the next day. The central idea of tea is that this day will never happen again. Every moment is precious, it will occur only once in a lifetime. Her words recalled the revelation I felt when Kano translated the meaning of the kanji he had painted for us at the end of our home visit in Kanawaza: “one encounter, one life.”

Then I was brought up short by another concept I heard for the first time. The tea ceremony is a way to pursue a particular state of mind known as “wabi,” in which the person is calm and content in a sense of profound simplicity. This named the elusive goal of our previous day’s wandering, the sensation I had felt in the teahouse in Kenrukoen gardens, and the apparant purpose of all classical Japanese landscape and architectural design. The tea room, she continued, is a sacred space, a dojo for tea. One must purify oneself and bow before entering. It has features that combine several traditional arts: a hanging scroll from calligraphy, beautiful wise words from literature and philosophy, boxes for tea from lacquer work, pot and cups from ceramics, and a vase of flowers from ikebana, the art of arrangement.

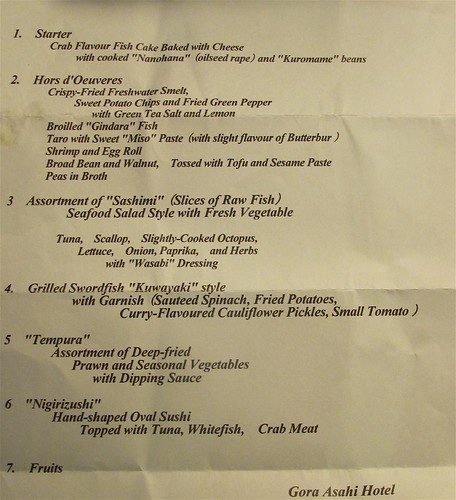

The pot is set to boil at the beginning of the ceremony, which normally lasts about four hours. First, lunch is served along with saki and kaiseki or sweet thick tea, which is sipped from a bowl that people pass one to the other to express harmony and respect. Then thin light tea is offered, one bowl per person, along with a candy to sweeten the tongue before the Machu or bitter green tea is served. This is made from the top five leaves of the tea plant, which are dried, powdered, and dissolved in the liquid to be taken into the body, for among other reasons, its high vitamin C content.

The tea is poured by the host or hostess into the cup, which has, like everything else, a front and a back. It’s important to turn the cup 180 degrees before drinking to make the front face outward. Interactions between server and recipients and among the recipients are always accompanied by bows. Each of the implements used–pot, cup, tea canister, and screen–have pedigree and significance.

The bus arrived at the gate of the monastery of Zuiho-in, and the clear cool morning air relieved some of the sinus pressure in my head.

Signs told us that this subtemple was founded in 1546 by Otoro Sorin, who converted to Christianity and became “influential” in East-West trade before Christianity was outlawed. I expected that the quiet atmosphere of this place would induce “wabi.” The paths were covered with a boardwalk to avoid the extensive construction work adjoining the temple.

We left our shoes at the entrance and entered a tatami room with a Buddhist altar on one side, and took places in whatever position was comfortable around the edge of the room, some kneeling, which my joints couldn’t handle, some in chairs supplied by monks flitting in and out, and some sitting cross-legged on folded pillows. People were clicking and flashing in the darkened room, but after one shot I concluded that taking pictures was highly inappropriate here and now. The abbot of the monastery entered briskly, a deeply tanned monk with glistening eyes and shaved head dressed in a smart black yukata over a white undergarment.

He sat on his knees and spoke in a crisp voice, alternating rapid staccato, melodic flow and loud laughs, pausing regularly for Maya to translate. He welcomed us to the zendo, explaining that once we entered this place we should leave outside the business of the street and the bus and the city and also of tv and cellphone and internet. We should come into the present moment and just breathe the air, in and out, give attention only to our breathing and our straight backs, which must not hunch forward. Good breathing and posture would provide long life and health, he said, it’s free and very valuable. Your life is just a certain number of breaths. Don’t think about the next stop on your tour or the last or what pictures you will take or what gifts you will buy or how much things cost. Breathing costs nothing. Be thankful.

In the presence of his vitality and radiant health I felt disgraced by my bodily condition: breath marred by coughing, hooked on decongestants, the turkey neck in the mirror I’d asked Jan for beauty advice about that morning, and her reply: “stand straight, don’t hunch forward.”

And my mental state was no better: the continuing picture taking by my fellow tourists agitated me with both righteous indignation and frustration that I couldn’t get the shots I wanted. Things settled down a little when the abbot rang a gong after telling us to look at the floor three feet away with half closed eyes and number our breaths. But I lost count quickly and instead thought about our obsessive photography. Is it a way to intensify the here and now while preserving it for later reflection and refinement, or a supreme evasion of living in the present? Is the urge to “collect experiences” with cameras, with journals, and with travel itself a way of treasuring what our one life has to offer, or is it an expensive form of distraction and trophy hunting?

After what someone later said was ten minutes, the gong rang again and the abbot spoke: “With a straight back while you exhale give a deep bow of thanks, and then rise with an inhale that will make you smile and improve your skin.” Next we were led into the tea ceremony chamber, where the monk quickly reviewed some of the steps Maya had outlined earlier. I was hoping that participating in the decorous ritual would reduce the turmoil I felt after his unsettling talk. But the picture snapping resumed and four or five apprentice monks scurried into the room bearing trays with pots and cups. One bowed quickly as he poured and moved immediately on to the next person. I tried to drink my cupful slowly but had to gulp it down since it was time to leave. The abbot passed before the row of picture-takers, bowing to each. Yet before I could return the greeting, he was out the soji screen. Why the rush I wondered? Was another busload of tourists right behind us? Could these visits be financing the expensive restoration outside?

My cold symptoms seemed worse as we paraded back out into the parking lot, and I didn’t feel like talking. When I wrote down some of my reactions in my little notebook during the hour long ride to the farm in Kameoka, both discomfort and disorientation subsided.

We were cordially greeted by three farmers and the local tourist promotion guide in front of a greenhouse at the edge of ricefields now growing spring green vegetables and were handed plastic coverings for our shoes and bags to hold our harvest.

After we snapped off crisp stems and leaves of plants resembling rappacini, they answered the questions of the group. They grow rice in summer, vegetables after the rice harvest. They use no chemical fertilizers or pesticides, manure and green manure only.

They’ve farmed this land, about 13 acres, for 13 generations and make a family living off it. They sell directly to local supermarkets. They’re helped by government price supports and crop insurance. When I told them about the Community Supported Agriculture program we belong to as an antidote to international industrial agriculture, they loved the idea.

The bus drove us through the rural district to an old samurai home, now a restaurant.

Rain mixed with snow as we were welcomed by the proprietor, a descendant of the original owners. We stood around tables stacked with ingredients, including some of the vegetables we’d picked, and she demonstrated the art of rolling sushi, then set us to making our own. After we sat down to eat, she and her assistants brought out five more courses to the meal.

Back in the hotel, we had only thirty minutes to prepare to meet our dinner companion, Stephen P., who had worked with Jan long ago as her appointee to the City Planning Commission and who later visited Japan and has remained for the last three years. We met him in the lobby together with Kayoko, his friend and English language student. She brought us a bag full of gifts and instructions on how to get to the hotel she’d reserved for our anniversary three nights later in Tomonoura, a fishing village on the coast. We gave her another Trader Joe’s chocolate bar.

We talked at length with Stephen about what we’ve all noticed that’s different about Japan”its cleanliness, efficiency, friendliness and politeness. He liked that people don’t complain or share any negative emotions. However, on the other hand, Japan’s has the highest suicide rate in the world. Stephen told us he loves Sumo wrestling. He’d wanted to take us to a session but we declined. Through the front door of the hotel, populated largely by foreigners, walked a large man with swept-back greased hair and a topknot in a full-length black coat. He sat solemnly texting on his phone behind Stephen, and Jan took their picture.

We took a cab to Stephen’s favorite Kyoto restaurant located in the Gion district, famous for geishas, cherry blossoms and tourists. Jan was cold in the pouring rain, but we lingered at a street crossing a canal to admire the herons.

Inside the restaurant twelve seats were placed at a counter around a pit where several women worked, dipping chopped pieces of fish and vegetables in batter, and one-by-one serving them to our plates.

We stayed for two hours, watching the rain turn to snow falling into the tiny garden in an airshaft behind a window.

As we headed for a cab back to the hotel, a blizzard of big flakes mixed with the cherry blossoms illuminated from below.