Peru Day 1

Preface

Back in September 2011 Jan and I purchased a three week tour of Israel and Jordan scheduled for February 2012 from Overseas Adventure Travel (OAT), the company that had provided us with a remarkable experience in Japan two years earlier. In early December we were forced to cancel the trip to deal with a family crisis. The insurance policy we’d bought to cover such situations would only refund a fraction of the cost and the balance could be credited to another trip only if taken before February 2013.

Our disappointment was kept alive by the diminishing possibility of redeeming the credit. In the meantime we had been assigned court-appointed custody for our eleven-year old grandson. In September 2012, we found out that he’d be visiting his father in Georgia for the winter school holiday and therefore we might have a two- week interval around Christmas to travel.

Ready to go anywhere in the world on an excursion already paid for, we searched the OAT catalog and came up with “Real Affordable Peru.” It fell within the allotted time and offered an appealing itinerary, including Lima, Cuzco, the Sacred Valley and Machu Picchu, which had intrigued me ever since I learned about it at age 10 in Richard Halliburton’s Book of Marvels. Throughout Jan’s hectic fall re-election campaign for Mayor, our bedtime reading consisted of Kim Macrorie’s The Last Days of the Incas, Mario Vargas Llosa’s The Storyteller, Mark Adams’ Turn Right at Machu Picchu, and Charles Mann’s 1491: New Revelations of the Americas before Columbus. But as the departure date approached, another problem loomed. The surgery that Jan had undergone in October destabilized rather than repaired her left knee, and she now needed a brace and continual icing just to walk city streets. How would she fare clambering in the heights of the Andes?

Day 1

We land in Lima 12:30 A.M. December 26 and are greeted at the gate by Jonathan, the OAT representative, along with a couple of intrepid fellow travellers from Chicago a few years our seniors. In the downtown, every building is protected by high walls or fences, and some of them have guard towers at the corners. The minivan drives along the Pacific shore toward Miraflores, the affluent tourist-friendly section of this city of 10 million. Jonathan assures us that the district has three levels of protection: municipal police, semi-official companies that contract with the police, and private security. We’re welcomed to Hotel Jose Antonio by a large African-Peruvian doorman in a suit and tails. It’s an upscale facility typical of those chosen by OAT and several notches above the motel 6 level I usually patronize.

In the bathroom we encounter the trip’s first culture shock: a sign tells us to dispose of all paper in the adjacent wastebasket, not in the toilet.

Our guide affirms that this means all paper, in order not to overtax the capacity of municipal sewage systems. It’s a contrast to the equally foreign peculiarities of Japanese toilets, which provided a warm water rinse of one’s undercarriage after every use. But it’s no more an adjustment than having to remember to always use bottled water for toothbrushing and sinus rinsing, as well as drinking.

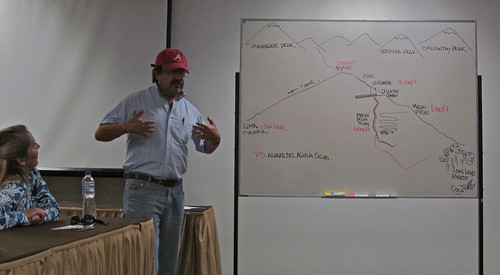

The morning’s generous breakfast buffet includes a thick, sour distillation of coffee one renders palatable by diluting with hot milk and water and a variety of delicious fresh fruit. Afterwards our group of 12 travelers assemble in a conference room for an introductory lecture by our trip guide Alvaro, illustrated with a timeline and map of the upcoming journey and including a strong recommendation that we ignore medical prescriptions for altitude sickness and instead drink coca tea and chew coca leaves, the time-honored cure.

Alvaro is a native of Cuzco”to be pronounced correctly as Qosco (just like Costco) in Quechua, the native language still spoken by the Andeans. He espouses a nationalism hostile to the Spanish conquistadores, ambivalent toward the short-lived Inca empire that they conquered, and partisan toward the decentralized pre-Incan native cultures whose histories extend back ten to twenty thousand years. He points out that modern Peru has recently rebranded itself with a new logo containing a spiral that’s found on inscriptions and also represents the concentric ancient terraces we will discover throughout the mountainous countryside.

We learn that his father’s family comes from the Amazon”most likely from Spanish ranchers–his mother’s from Andean Qosqo, making him a mestizo like most other Peruvians since the Conquest. There’s a familiar anti colonial, anti-imperial bias in his views, but they are mixed with great enthusiasm for his longtime employer, OAT, which is dedicated to educating Americans about foreign cultures and environments, promotes international understanding, underwrites local social service programs and has provided his family with the resources to send his three children to University.

We depart for a group promenade down the busy main boulevard of Miramontes. There are no beggars or street sellers and a prominent presence of kevlar-vested gun-toting police and private security patrols. A building across the street sports a huge mural depicting a prostrate Gulliver-like figure with tiny trucks driving away from a hole near his heart. Alvaro interprets: this is the heart of Peru being eviscerated by the mining industry.

We amble through Kennedy square and down another boulevard to a restaurant for our first meal of legendary Peruvian cuisine, passing a long line of respectable but unhappy-looking people lined up at one of the many prominent banks. These, says Alvaro, are civil servants lining up to cash (or receive?) their paychecks. Jan and I both order ceviche, and the raw fish marinated in lime juice and a light cream sauce with sliced onions reminds me of the sashimi which introduced our culinary adventures in Japan.

Back at the hotel we are introduced to Dante, our local guide, a compact man with glossy black hair, shiny eyes, a mime’s expressive gestures, a shaman’s intensity and a distinctive profile like those on Aztec and Mayan reliefs. He was born in a small village north of Lima into a family of subsistence farmers and moved with his parents and brothers to the city when he was nine years old. He hated to leave his beautiful rural village but since then has learned why it was the right choice for his parents.

We arrive at the National Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, an attractive ochre and white colored building with a central courtyard graced by brightly flowering trees and loudly chirping birds. First stop for the group is under an arch bearing the ubiquitous “S” for Sismo sign”a supposedly safe sanctuary in case of Seismic disturbances. Peru’s history and culture is dominated by earthquakes; the last big one in 1970 rocked Lima for two full minutes and caused a hundred thousand deaths. The damage to this museum has still not been fully repaired due to the government’s according higher priority to developing the infrastructure–roads and bridges facilitating commerce across the extraordinarily difficult terrain separating the three primary areas of the country: coastal desert, mountains, and Amazonian jungle. Peru’s immense archaeological riches have only been properly excavated and preserved with foreign financing.

The Museum’s exhibits are displayed in chronological sequence and Dante emphasizes the ingenious technology for resource use of the earliest strata”stone age tools similar to those of the early California Chumash I saw on a recent school visit with my grandson to the Rancho El Chorro Education center.

As we move to the display of a stela depicting the puma god holding staffs of peyote cactus, he points out that the physical evidence here suggests the existence of an agriculturally based civilization even older than Egyptian, Sumerian or Hindu”the Chavin culture. This new view of the age, size and complexity of New World cultures is amplified in the book that Jan and I are continuing to read as we travel, Charles Mann’s 1491.

Though none of the New World cultures seem to have invented the wheel or the metallurgy that could produce powerful weapons, their hand-formed pottery glazed with characteristic red ochre looks as if it was thrown, and both human and animal figures are elegant and expressive.

From early times onward music has been ubiquitous in religious ritual as well as daily life, and the instruments displayed are themselves beautifully sculpted artifacts.

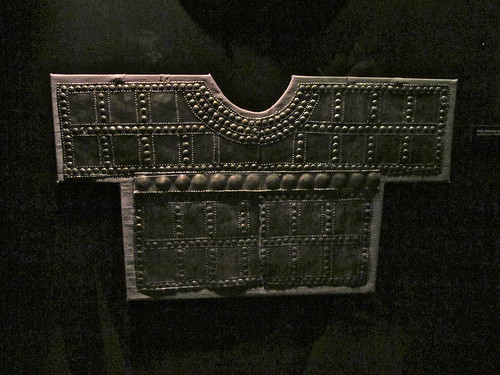

A darkened room displays Inka treasures, some of the few remaining examples of the vast trove of gold and silver architectural features, sculptures, ritual instruments and costumes that Pizarro and his tiny band of invaders pillaged, melted into ingots, and sent back to Spain during the sixteenth century.

On the bus trip to the City Center, Dante points out a fortress-like structure rising behind a large fenced area, one of more than 40 major excavations now being carried out within the city limits, an indication of the nation’s hidden reserves of archeological resources.

We pass a heavily fortified complex of buildings suggesting an Inca temple that he identifies as the Japanese Embassy–the scene of the 1996 drama initiated by the Shining Path guerillas who took over the complex, held people hostage for 126 days and finally were defeated by police and military commandos under the direction of then president Alberto Fujimori. Dante says he voted for Fujimori and found him an effective leader whose strong-arm tactics were necessary to combat the murderous Maoist movement wreaking havoc in the country. But like most Peruvians, he became disillusioned with Fujimori after the brutality of his methods approached those of the revolutionaries and after revelations of large scale corruption caused him to flee the country.

Our bus maneuvers through fast moving traffic toward the center of Lima, the end of every street revealing arid mountains covered with ramshackle homebuilt structures sprawled in growth patterns that look like lichen on rock. These suburbs are the newest and poorest parts of the city, Dante says, unlike in America where the more expensive homes are up the hills.

We enter a traffic circle surrounded by shabby mansions that used to be the homes of Lima’s aristocracy and are now divided into crowded apartments. He assures us that the central square where we are headed is safe and heavily patrolled.

The square is fronted by a 16th century cathedral and bishop’s palace, the 19th century Presidential palace and the18th century City Hall. It’s decorated with ugly artificial Christmas trees.

The atmosphere is fast and lively, the pace set by the machine gun staccato of Spanish speech and laughing children. Dante says that Lima’s mayor is a woman and observes that it is important for women to be involved in politics. He’s impressed to hear that Jan is a mayor and promises to arrange a meeting between her and the city’s chief executive when we return.

The group walks a block past street vendors whose fascinating appearance and merchandise we try not to eye into a square dominated by the baroque façade of the San Francisco monastery and cathedral, as harmonious in proportion and dramatic in decoration as any churches in Europe.

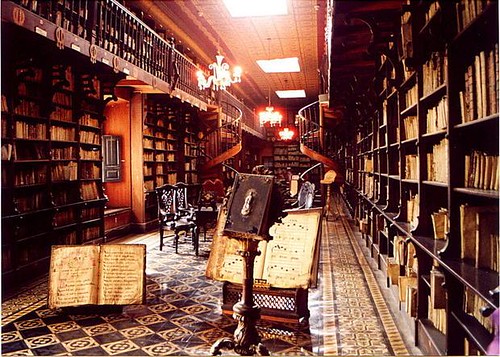

We enter the adjoining monastery where photography is prohibited, stopping at the library where light pours in from clerestory windows above a three tiered gallery and illuminates the dust in the air coming off thousands of leather-bound books that seem haphazardly shelved and piled, most of them with pages rather than spines facing outward. In contrast to air-conditioned and immaculate rare book rooms in American libraries, this place looks like 18th century paintings of royal libraries, a place as full of buried treasure for researchers as the landscape outdoors.

Dante says that the Franciscan missionaries accompanying the conquest and glorified in this building brought largely destruction and horror to this country, but two imports deserving appreciation are libraries and universities.

We walk through a wide second story colonnade surrounding a garden of mature fruit trees. Most of the pillars are out of plumb and the wide tiled floor tilts and ripples as a result of earthquakes. Then we descend through claustrophobic adobe passages crowded with other tourists to the Catacombs under the cathedral. This was the only cemetery of Lima for its first 200 years, and it holds the bones of 25000 of its most illustrious citizens sorted into different parts of the skeleton”skulls, femurs, tibias, pelvises”arranged for display in symmetrical patterns in ditches along a maze of passages and at the bottom of circular wells 20 feet or more deep.

Here is a foretaste of the ubiquitous presence of preserved bodily remains of the dead, in private homes, Inka temples and Christian shrines.

Arising from the catacombs, we emerge into the light of the square and the sounds of children laughing. A car backfires and we’re engulfed by a swirl of pigeons.

After a siesta back at the hotel, Jan and I retrace our steps toward Kennedy square and find a pleasant café for a late dinner at a price similar to what we’d pay at home. On the way back to the hotel at 9:30, we wander into the still open municipal art gallery and find a display of Peruvian arts and crafts”modernistic variations of traditional corn-beer drinking vessels, an installation of dried vegetation stuck to walls and ceilings suggesting the jungle, and whimsical ceramic musicians in colors and postures reminiscent of the ancient pottery in the museum.

Slideshow of these and more full-size photos