Peru Day 2

On the way south after breakfast, Dante has the bus stop for a look at Lima’s long beach front and pelicans on a fish processing plant’s roof.

Fishing is a major industry because of the upwelling of the cold Humboldt current just off the coast. A hearty stranger approaches and hails us.

Fishing is a major industry because of the upwelling of the cold Humboldt current just off the coast. A hearty stranger approaches and hails us.

He says the large green boat in the foreground of the picturesque fleet is his.

We pass a woman’s prison that incarcerates not prostitutes”the trade is legal in Peru”but mules”young women recruited by dealers to carry illegal drugs out of the country in their body cavities.

A mountainous sand dune reminds us that we’re in a coastal desert, one of the driest places on the planet. The top and steep slopes are crisscrossed by bulldozers harvesting sand used in a factory at the base of the dunes to manufacture bricks.

The mined dunes are succeeded by a grove of young orange trees planted on the slope, and then by a dense colony of shacks.

This is one edge of Villa El Salvador, a sprawling zone of improvised and unplanned buildings that constitutes the rapidly expanding suburb that now houses about 400,000 people. Most have left their ancestral homes in the Andean highlands and other regions of Peru and migrated to the city–fleeing the terror inflicted on peasants by Shining Path guerillas, forced off their land by famine and drought, or in search of a better life for their children. Known as “invaders,” they squat on unused private and public property, build with scavenged materials and survive without basic services like water, sewage or electricity. They eke out a living selling services and labor at low wages or creating small-scale businesses peddling food or souvenirs on the street.

In 1980, after a series of violent conflicts with police who tried to evict the squatters, the government created a new policy: if a group of squatters lived on the land for ten years and came up with a lawyer to represent them, they would be granted ownership of their lots. And if they continued to organize and pool resources, they could petition for the construction of roads and the delivery of other basic services for which they would pay monthly bills. The older these squatter communities, the more established and prosperous they have become, and now they are classified as class 1, 2, 3, and 4, the last including conventional stores, hospitals, factories and other locally owned businesses. But at no stage, Dante insists repeatedly, do the residents of these communities receive welfare from the government. They are responsible for supporting themselves through hard work, austerity, persistence, ingenuity and most important, cooperation. He confides that he himself grew up in a community like this.

We get out at a complex of Inka structures. A partially reconstructed dormitory for priests and sacred virgins fronts on a wetland oasis created by aqueducts conducting water from a river flowing down through the coastal desert from the Andes.

A hilltop Temple of the Sun overlooks offshore islands that were assumed to be the residence of gods who required sacrifice of the virgins to continue providing crops and fish.

The structures are built out of adobe bricks of the same color and texture as the soil from which they’re hewn. Occasionally we see evidence that originally the structures were surfaced with sharp angled stucco painted with the red cochineal dye.

At the summit of the temple a heavily armed soldier stands at attention, part of a contingent protecting the site 24-7 from continuing harm by looters.

Back in the bus Dante says we are about to visit a stage 1 squatter community nearby which has a special relation with our OAT tour company. On every visit, the guides bring bags of rice and beans and provide other necessities in kind. We pass through a checkpoint staffed by local residents who patrol the unpaved streets to make them safe for children, who would otherwise be threatened by abusers and sex traffickers.

Dante greets the guardians who let us through the gateway. Tiny shops are scattered among the houses crammed side by side, some no more than a patchwork of cardboard and tin roofing, others ambitious and creative in style.

2840

2840

Almost everything here is salvaged, recycled and improvised, but the atmosphere seems secure and cheerful.

Children play in the narrow lanes, a mother holding a baby hangs up laundry, a man washes his dog.

Dante leads us to a corner building deep inside the grid of streets. The mothers here have organized a soup kitchen to feed those who don’t have enough to eat. Nourishing food is offered, not free but at very low cost along with information about nutrition and health. There is one of these kitchens for each 70 families. Some support is supplied by NGOs but not by the government. The woman who runs this kitchen shows us the large clean pots, the propane stove and tank, the sign on the wall that warns against cheating or hoarding. She is proud of the place, but not happy today, because for unknown reasons no food has arrived.

This community has been nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize for its successful experiments with alleviating poverty and promoting community development. Its approach struck me as diametrically opposite to that in our home town, where a complex permitting and review process by the existing community is required before any new construction can take place. It also takes an opposite approach to our growing problem of homelessness which assumes that the government and existing community provide housing, food and safety for those in need who play by the rules.

As we board the bus I see two boys starting up a game of soccer in a well-fenced dirt field.

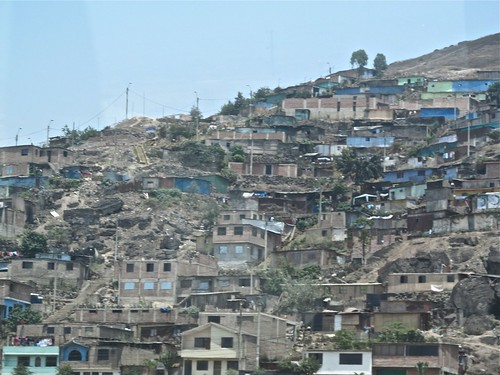

Now we drive through a stage 2 community perched on a steep hillside. The ground here seems as unstable and incoherent as the teetering structures. There’s little danger of erosion since it never rains in Lima, but I envision the whole warren sliding down the hill in case of am earthquake. Rather than roads or sidewalks, one sees only footpaths and cart tracks.

But the people who construct and continually add to these structures with locally manufactured bricks and cement seem to have inherited the Inca tendency to never stop building on near-vertical slopes. To many people, improvised structures like these are merely an eyesore, but I find them more aesthetically appealing and mechanically intriguing than the modernist architecture of the luxury hotels of Miraflores.

Our tour of Villa El Salvador concludes with a bus ride through a stage 4 section of this “new town.” In narrow paved streets we see into small furniture and shoe manufacturing operations, the merchandise being loaded onto small pickup trucks or motorcycle driven carts.

And then a main boulevard with grassy medians, a large hospital, and an unrelenting barrage of billboards.

We return to our posh hotel for a rest and then are driven to dinner in a restaurant in the even more exclusive seaside enclave of Barranco.

Slideshow of these and more full-size photos