Peru Day 3

A 5:30 wake-up call marshalls us back to Lima airport under Alvaro’s direction for the flight to Qosqo, the center of the Inca empire and of present day Peruvian tourism. On the way he regales us with stories from the Inka history that he identifies as his own heritage, occasionally speaking in the Quechua language that they imposed on its diverse communities during the less than hundred year duration of their rule in the 15th and 16th centuries.

After a three-hour delay and two gate changes, we fly for ninety minutes and land at the Qosquo airport situated in the center of the city. Signs proudly exclaim that it is soon to be replaced by a much larger international airport on the outskirts. I fear that the expansion of industrial tourism this brings will eradicate whatever is left of the native cultures and archaic way of life we’ve come here to appreciate. That at least is what happened at Cancun in the Yucatan, which we travelled through three years ago to attend the wedding of our niece in Playa del Carmen.

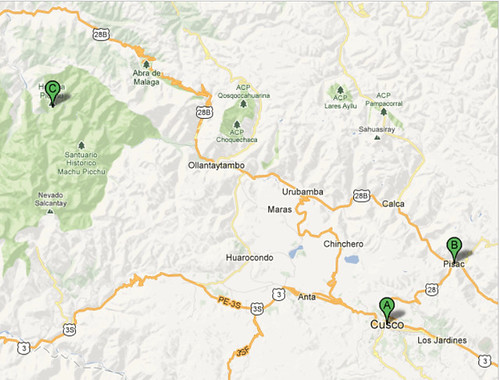

To help us adapt to the altitude change, we will descend to the 6000 foot level in the Sacred Valley of the Urumbamba River for several days before returning to this 11,000 foot city.

As we exit the terminal, there’s a clap of thunder and sudden mountain downpour. Alvaro reminds us that summer in Peru is the rainy season and that abrupt weather changes are to be expected. However he will be praying to the Apus”the Inca spirits of the mountains”to provide us with sunshine at Machu Picchu.

In the still pouring rain”the snowline in this near equatorial latitude is 14000 feet–the bus winds above the City nestled in the valley below.

Alvaro points out rock formations and walls that mark the Inca holy places (Wasi) and agricultural terraces that cover the countryside.

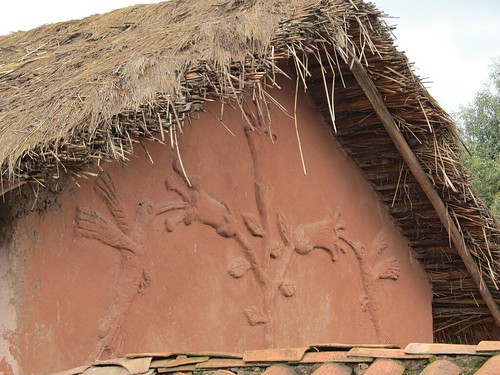

We stop at a settlement on the pass above Qosqo to view new peasant structures that incorporate traditional ceramic bas-reliefs, thatch roofs and shrines that meld pagan and Christian images. We encounter campesinos herding sheep and pigs and selling native crafts to tourists.

It’s hard to believe that this is not all part of an Andean theme park, but as we start downhill following the course of a mud-swollen stream, it’s clear that we’re in a real archaic landscape where homebuilt houses and subsistence farming still prevail.

The streambed deepens into a canyon with steep rock walls rising on the opposite side.

The road turns and we stop for a new view. The canyon we’re in converges 1500 feet below with a wide valley flanked by mountain ranges on both sides whose tops disappear into the clouds. Through it runs the Urumbamba river flowing westward toward our destination, Machu Picchu, and downward toward the Amazon. Directions are confusing; I expect the Amazon to be across the Andes to the east, but the map shows the range in this region angling from a north south to an east west axis before resuming its general orientation further north. At this overlook, I imagine the route taken by the rebel emperor Manco Inka and his retinue as they fled Qosqo pursued by the Spanish over the mountains and into the jungle.

This is the Sacred Valley, known for its fertility and beauty and the magnificence of its archaeological resources. Alvaro prays to the Apus while the rest of us take pictures.

At the convergence of another river on the opposite side of the Urumbamba the town of Pisac comes into view below precisely spaced and angled walls that terrace the nearly vertical rock faces. How could they have been constructed in the first place and how could they have lasted in earthquake country another 500 years?

We cross the river and stop to wander through the narrow streets of the ancient market town. I’m drawn in by two little girls in Andean costume cradling a bleating lamb and a puppy.

In return for the picture I put a sole (about 40 cents) into one of their outstretched hands.

The bus ascends through a gully behind the town, providing a closer view of the terraces, many still cultivated with corn and potatoes by local farmers whose chickens and cows share the road with us.

As we get higher, the terraces take the shape of an amphitheatre and are no longer farmed but part of an archaeological preserve. We walk on a stone path toward a temple fortress overlooking the valleys below and a stone village above.

A woman in traditional garb insistently offers handicraft merchandise laid out on colorful blanket. No one is buying so she folds up her wares and walks toward the village.

The bus heads back down to the river and drives through tiny villages strung along the road. We pass a supply yard storing great piles of 24 inch pipe that will bring natural gas from the Peruvian Amazon through the Sacred Valley to Qosqo and Lima. “This will be tremendous for us”cheap energy to fuel economic development.” Says Alvaro. I think about the melting glaciers above us and the protests in the U.S. against natural gas fracking and the construction of the XL pipeline from Canada to Louisiana.

In the town of Urubamba, the bus turns off the main road down a bumpy little lane and comes to a halt at a mud puddle. To reach our lodgings we walk over a stone wall, through a wet potato field, and past a new adobe gateway, accompanied by the sound of the rushing river below.

Just past a tree full of ripe papayas, the Urubamba Villa sign comes into view.

A massive portal opens on a beautiful prospect: immaculate lawns, flowery rock gardens buzzing with hummingbirds and butterflies, fountains and ponds surrounded by a portico supported by peeled timbers secured to beams with braided rawhide lashings.

At the center of the garden stands a circular sanctuary topped by a high dome.

For two nights, this is to be the base camp for our approach to Machu Picchu.

Slideshow of these and more full-size photos