Michael Friedman: November 18, 1942 – September 5, 2014

Michael made me feel secure in Lund when I felt most exposed. There was something about his domineering figure, his booming voice, his grandiose self-confidence and his awe-inspiring talents as artist, writer and chef that made me feel protected, as if by the big brother I never had. Even when he told tales of disappointment in love or family or career or business–with a puzzled shrug of the shoulders and lift of the eyebrows–his presence seemed sheltering. Never mind that he rarely showed interest in what I was up to, either at home or abroad.

Perhaps I placed trust in Michael because we arrived in Lund at nearly the same time as refugee idealists groping for space to rebuild the world in accordance with our own fantasies, each of us in flight from the world of friends and family back home, but still longing for their admiration. Perhaps it was that the large tracts of land we owned (or rather owed) shared a corner in common, and that we were both concerned with property lines and subdivision potentials along with goat milk and chicken egg yields. Or that our two first children, Jonah and Josh, lived within a half hour’s walking distance and were best friends. Perhaps it was that we were both products of a strong liberal arts education that we expected to put to work in the bush, or that we self-identified as non-observant atheist Jews.

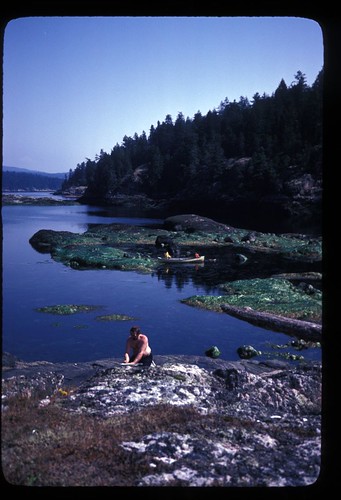

In 1972 we decided to go in together on a major investment: a green fiberglass 16 foot Frontiersman canoe. Neither of us were fishermen or marine types, but this was a shared opportunity with limited commitment for unlimited adventure: to get out on the water, to camp on the Raggeds, to go on a four-day trip to Galley Bay through Portage Cove when the boys were three, and, when they were five to let them paddle themselves from Lund to Steamboat Bay and camp alone overnight. Here’s a picture of him working on one of his amazing superrealist paintings of the rock cliffs across the channel, as Jonah and Josh practice boat-handling.

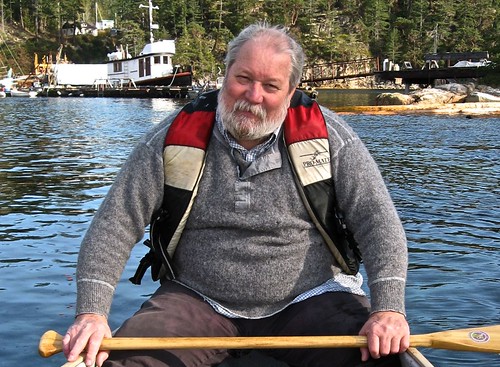

In 2005 we tried again, as grandfathers, to paddle the cracked and faded hull to the Raggeds, but his weight in the stern made the vessel so tippy that we turned back before reaching Finn Bay.

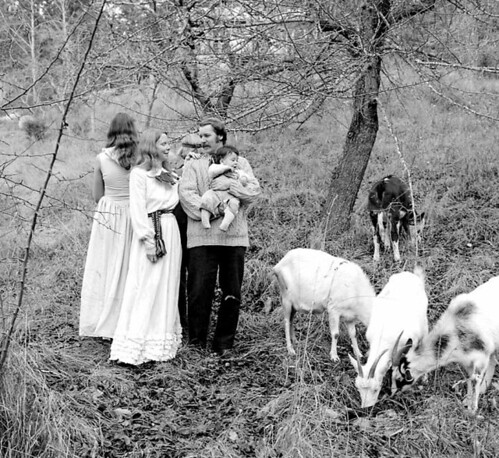

Michael was a natural master of the theatrical, as evidenced, for example, in the dramatic proportions of the space he created inside his dilapidated mansion on Prior Road, and in the double wedding with babies, goats and cats he orchestrated in his pasture, here photographed by Fred Pihl.

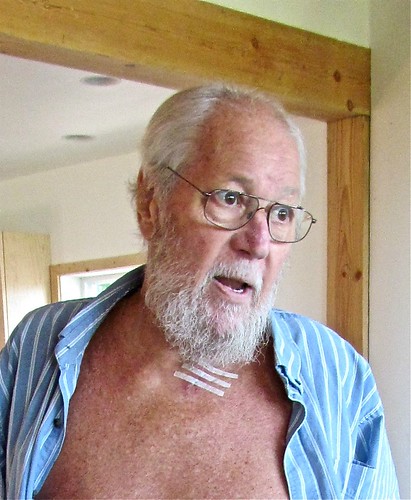

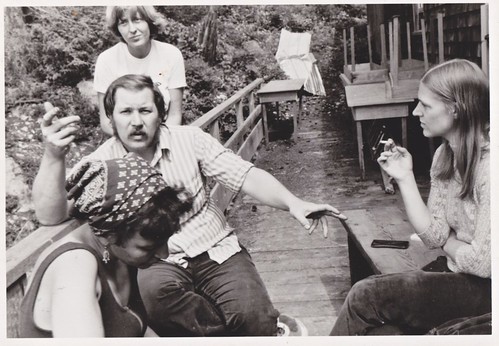

After its first production of Free to Be You and Me, Michael belatedly joined the Lund Theatre Troupe and directed and designed a haunting performance of Spoon River Anthology, the third of Three One Act Plays. In spite of his tendency to overshadow the rest of us, the huge infusion of his presence was gratefully welcomed as taking the company to the next level. Here is a 1975 photo of Michael holding forth on the back porch of the Community Hall on the morning after the all-night cast party during a meeting to plan taking the show on the road.

In later years, as many of the founding members departed, Michael kept the Troupe going himself, as producer, director and script writer.

A year or two after Jan and I started working at Malaspina College in Powell River ”1976 or 77”Michael was hired to instruct studio art and art history courses there. Again his talent and energy provided a big boost to what we were trying to do”beef up the liberal arts program to make it possible for local people to actually complete a community college degree without leaving the area, not to speak of expanding local job opportunities for newcomers. The first such graduate was June Huber, brilliant as both an artist and a writer, whom Michael and Jan shared the privilege of teaching. She and most of the other students adored him for his ability and his dedication.

We moved back to the states in 1979, and Michael and his family settled in Los Angeles a few years later. We had occasional contact”eating lunch at the old Getty museum where he combined his cooking with his interest in art, and visiting the house in Culver City he rebuilt with his own hands. We’d cross paths on summer visits to Lund. I was amazed but not surprised when he worked his way up to head chef at Biola University, planning and providing daily meals for 4000 people, meals good enough to attract faculty as well as students to the dining hall. I wasn’t surprised either when the corporate hierarchy forced him out of his job in order to bring in the non-descript cooking of a food service.

I have vivid recollections of his return to Lund in retirement, his living comfortably within the confines of his fifth-wheel mobile home near the foot of the old castle on the hill, his absorption in the unending hassles of subdividing and selling the lots he designed, his contentment sitting by his little koi pond like an old Zen sage, his artistic experiments in multiple media–digital, painting and sculpture–and, though maybe it was only my projection, a sense of his great loneliness. The fact that he was back strengthened my tie to the place where my present converges with my past.

Having finally overcome the financial obstacles, he set about to fulfill his ancient dream: building a comfortable and beautiful home with a million dollar view and a gourmet kitchen. He loved working on it, living in it, showing it off to friends and neighbors and international visitors he attracted through Air BnB, whose glowing digital recommendations he treasured.

But as soon as he moved into this bright and airy house with a sold foundation, his body started crumbling. First the esofogeal cancer that cruelly kept him from another great joy in his life, eating, and then after a heroic and apparently victorious struggle with that, the double assault of metastatic bone cancer and a lingering infection in his leg from a cut by his woodcarving chisel. I would check in on him periodically during these ordeals, and his demeanor was always positive, proud of his weightloss, high as a kite on his medications, confident he’d beat the odds.

During our annual visit and family reunion in late July, Michael showed me and Joe around the house, delighted with the appreciation of his work expressed by his former daycare charge and now fellow design-builder. Our last face-to-face took place at Jan’s birthday party at Knoll House. Climbing the stairs to the living room left him breathless, but he carried up a large pot of Cioppino he’d prepared for the potluck that Jan said was some of the best food she’d ever tasted.

Despite the conviviality, I sensed his peril. Back in California, I called repeatedly and got no answer. After ten days, he picked up the phone and spoke between gasps. He said he’d been in the hospital because of the leg infection and was now home again on a double ration of oxygen. It was scary, he said, not being able to get enough breath. I asked if anyone was there looking after him, and he brightened and said, “Don’t worry, the home care people come twice a day, it’s alright.” The conversation was exhausting him so I said good bye, horrified that he was alone in such an extreme state. I phoned Mara, and she too was horrified by what was going on. She assured me that she was doing her best to help and that Janet McGuinty was coming up to add what support she could.

Two days later I listened to a brief phone message from Mara informing me that Michael had passed”at night, at home, in Lund. I was, as they say, overcome with grief”more than I expected because of the suddenness of the news and my assumption that he had died frightened and alone. I couldn’t bear the thought alone myself and called Jan at the Mayor’s office and wept into the phone.

Then I called Mara and spoke to her and to Janet. The ending was opposite to what I’d imagined. Both of them were by his side, Janet holding his hand. His last words were “this is such a comfort.” I saw three old friends, returned to the place where they met more than 40 years ago, feeling their bond at a moment that counted most. I felt part of that bond.

Next day I called Linda Friedman in Hawaii. Michael had told me she was with him for a brief visit in early July. I hadn’t spoken to her in ten years. As soon as she heard my voice, she said, “Funny you should call. Michael communicated with me just before I woke up this morning. It was more vivid than a dream. He said, ˜I loved being Michael Friedman. But where I am now, I love so much more.'”

July 27th, 2015 at 2:08 pm

Beautifully written,Steven,and a tribute to the man