London July 26

Ready for more unplanned adventures before attending tonight’s play, we cautiously crossed the wrong-way street outside the hotel

and boarded a bus headed for Putney, the terminus of a Thames River boat line. Billed as a commuter ride rather than a tourist cruise, one couldnt determine from the website or the app whether “Uber Boat by Thames Clippers” was part of the public transportation system or a private operation.

The stop nearest the dock was called Battersea Power Station, located a block away from the river in a pedestrian-unfriendly maze of criss-crossing tunnels, overpasses, temporary barriers, and littered sidewalks. After bewildered efforts to follow the google map we were guided back toward the river by some reliable looking signage behind which rose the Power Station’s landmark brickwork, flanked by modish landscaping and a diverse panorama of shiny new buildings.

Walking down the clean wide footpath, we passed between two peculiar structures: a brightly colored children’s playground

and a massive edifice with just as playful an appearance, designed to avoid any familiar volumes, shapes or lines that the eye could rest upon.

Curious about what looked like a tottering pile of blocks towering over us, I learned from the phone that this was an apartment building designed by 94 year-old Frank Gehry, the architect whose other work had swept me away in L.A.’s Disney Hall and the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao Spain.

I’d have loved to linger as we had on the grounds of the Bishop’s Palace, but the even stronger draw of the former power station was irresistible.

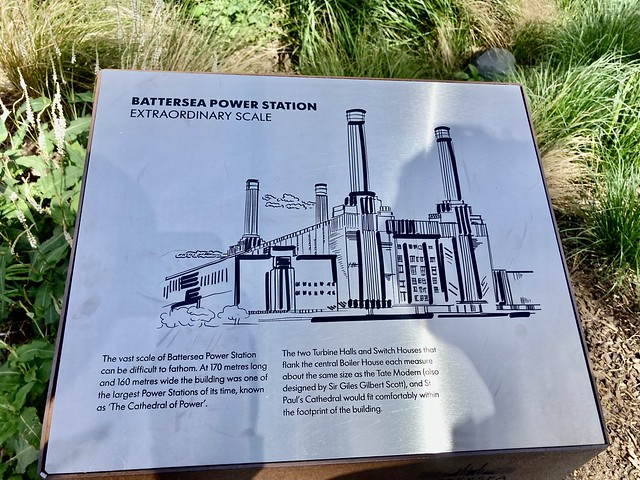

As at Fulham, some of the effect had to do with discovering the place unexpectedly. But apart from that, this building was a famous architectural masterpiece known in its day as “The Cathedral of Power.”

It was built in two stages: the first completed in 1935, the second not until 1955 due to delays caused by World War II. It supplied a fifth of all of London’s electricity by burning coal transported on the river. It was fully decommissioned in 1983 because of inefficiency resulting from wear and tear and growing opposition to coal pollution. Appreciation for the building’s architecture led to its listing for preservation, but the whole 42 acre riverfront site sat unused until 2020, when a consortium of Malaysian investors began the redevelopment that concluded with the Power Station’s opening as the site of high end residential, restaurant, retail and entertainment spaces in October 2022.

As opposed to the unique forms and textures of the building’s exterior, the repurposed interior left me cold, reminiscent of any number of high-ceilinged elevator-ornamented hotel atriums.

Rounding the corner outside, we saw the river beyond a graceful park, plaza and fountain area that welcomed some cheerful multiracial families.

Decelerating fast and smooth from high speed at the dock the boat quickly loaded passengers and took off down stream. Passengers were required to remain inside the cabin. Shiny skyscrapers sprung up from what I’d remembered as a low rent district of the South Bank also recently redeveloped

The houses of Parliament and Big Ben we’d passed on the bus last night flew by

and this time we passed under Westminster Bridge a bit wistful about not being able to mount aloft the London Eye ferris wheel

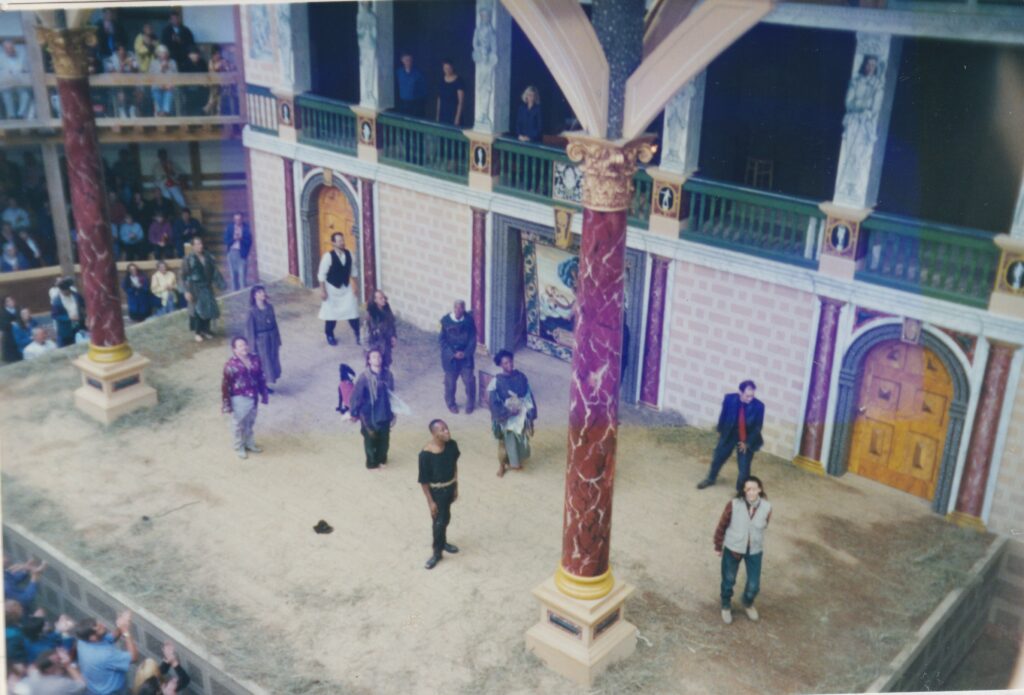

or revisit Shakespeare’s Globe–a faithful reproduction of the sixteenth century theatre now dwarfed by encroaching new construction

whose opening production of Two Gentlemen of Verona starring a youthful Mark Rylance (at right rear) had left us transfixed in 1996

and enchanted by a mature Vanessa Redgrave as Prospero in The Tempest in 2000.

Across the river loomed the Dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral

recalling a 1996 photo from the Bankside

and “the Shard,” whose pinnacle, largely financed by the Arab State of Qatar, rivals Gothic cathedrals in soaring 72 stories to heaven.

Debarkation point of the river bus was the Tower of London, the oldest and most popular tourist attraction of the City, where we avoided crowds lined up for miles to get inside

We stopped briefly by a genuine remnant of the London Wall built by the Romans around 200 C.E. now serving as a shady retreat for tired sightseers. It’s fronted by what looks like an antique bronze statue of the period, but is actually an early 20th century cast of a first century portrait of the emperor Trajan found in a junkyard, the original still on display in the Archaeological museum of Naples.

Looking forward to our afternoon nap, we dragged ourselves up the Tower Hill to the Metro Station for a quick ride back to Gloucester Road, surprised by other passengers offering us their seats.

Before we could tackle the 40 steps leading from the romanesque arches on the platform to the Bailey’s Hotel, we got to admire an art installation by Monster Chewynd called “Pond Life: Albertopolis and the Lily.”

According to the online explanation,

The sculptures reference the commemorative coins, medallions and souvenirs that were created to commemorate the Great Exhibition [of 1851], as well as the array of terracotta animal sculptures that decorate the exterior walls and vaulted galleries of the Natural History Museum…A freestanding salamander, holding an Amazonian lily pad as a parasol, is an anthropomorphic addition to this scene of amphibian industry.

As did the performance of Beethoven’s ninth, the availability of tickets for Patriots during its short run seemed a boon. This contemporary history play by Peter Morgan, the author of the Netflix series, The Crown, chronicles the rise of Vladimir Putin among billionaire oligarchs after the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union, its theme made shudderingly relevant by the war in Ukraine.

The first act depicted the the feeding frenzy among businessmen “patriots” pillaging the public resources of the communist empire with capitalist abandon. The most effective of them, Boris Berezofsky, a brilliant mathematician shifting careers to billionaire kingmaker, facilitated Putin’s rise to power but eventually succumbed to his protege’s ascendance. With spicey dialogue and fast paced action the play was highly entertaining and also instructive in shaping a narrative of what led from the hopeful “perestroika” reforms of Gorbachov to the present sinister regime.

The second act took place where we were, the city known as “Londongrad” for serving as an international headquarters of Putin’s allies and rivals. In classic tragedy mode, it traced Berezofsky’s machinations from rise to fall concluded by isolation and psychological disintegration.