I had been feeding the pigs extra ration all week to use up what was left of the Hog Grower. They sounded even angrier than usual on Saturday morning, when I didn’t stop at their pen on my round of chores. By the time I finished rinsing the milk strainer, Jonah had already belted himself into the front seat of the car.

I floored the accelerator for the five mile trip down the highway to his friend Jimmy Cox’s house, where I had arranged for him to spend the day. The inside of “the wagon wheel place” felt strange to me, its walls lined with trophies and racks of guns.

Back home, 1 started preparing. I redug the old fire–pit in the backyard, split a good sized pile of dry cedar and alder, and scoured out the forty gallon drum. I set the drum over the pit, staked at a 45 degree angle against the heavy work table, so that we would be able to dip and pull while scraping the hides. As water from the hose slowly filled the drum, I kindled the fire. Then I went over to the collapsing root cellar and sawed off two maple branches growing through its roof. I sharpened them at both ends to make spreading sticks and placed them on the table next to the coiled ropes, the pile of folded gunny sacks, the whetted knives and the .22.

I was feeling anxious, but more focused than usual. I had to be ready by 11:00 o’clock, when Terry Kurtz, my experienced neighbor, was coming over to help out. As I had explained to our visitor from the city a few days earlier, slaughtering animals no longer disturbs me, as long as the process is carried out with order, precision and respect for the animal’s gift.

At 11:15, Stan, who lives in the loft of the barn, came out of our house wrapped in a bath towel. “Terry called to tell you he’ll be late,” he said. “His boat started sinking last night, and now he’s stripping the copper and brass off before it goes under.” I closed my eyes. A small bubble of panic popped at the back of my neck. ” I know what that means. I’m going to lose another day. Jonah comes back at 4:30. Janet is away for the weekend. Those pigs have started rooting under the fence and destroying the apple trees…I could be at the typewriter right now…If only Stan wasn’t a goddamn vegetarian.” I paced the yard for ten minutes trying to decide whether to pack it in or head down to Lund.

“Maybe if I help Terry, there’ll still be time,” I mused, climbing back into the car.

Down at the dock, it was low tide. Terry’s boat was beached on the exposed concrete ramp, leaning against the pilings of the wharf like a drunk against the hotel railing. It was a huge old cabin cruiser, with a sleek, beautifully proportioned hull. But below the waterline its shape was lost in a fuzzy mass of seaweed, barnacles, and mussels. The point of the prow was dulled with black rot. The solid mahogany planks of the deck were grey and warped, disclosing the splintered seams underneath. A large hole had been chainsawed through the cabin roof. From the wharf, I looked down and saw two men inside , fitfully hammering and monkey-wrenching. They moved slowly, without a sense of purpose or direction.

As I climbed down, I felt as if I were entering the old hulk in Through a Glass Darkly, the film I had just shown in my nightschool class. It stank of diesel oil and garbage. The surfaces were scabbed with rust or smeared with grease. Tools, paint cans, hardware, cooking utensils were strewn everywhere. Terry was unscrewing a lock from the cabin door. “The only reason I’m taking this is that I’ve got the key,” he said.

Terry’s belly bulged through the holes in his Indian sweater. His small legs seem swallowed up by his gumboots. Where it wasn’t hidden by flowing red hair and beard, his face showed the texture of a young boy’s. His small blue eyes bore their normal expression: was it hangdog or was it blissful?

Before the lock came loose, Terry stopped unscrewing, crouched, and started emptying out a cupboard under a counter. He was mumbling:”…there’s still some thinner in this…copper paint is expensive…the hell with that skillet…” He tossed the chosen items into a soggy cardboard box and dropped the discards into the puddle in the center of the floor. “…somebody’ll be able to use this stuff…I’ll keep it under my shack…when the tide gets low enough, I’ll try and get the shaft out – it’s worth at least a hundred bucks…I’11 get Lloyd to tow her over to Finn Bay and torch her on the beach…can’t get anyone to take her now, not even for nothing…I’ve been wanting to strip her for a long time …been a millstone around my neck ever since I got her.”

“It doesn’t look to me like you’re going to be in the mood to butcher pigs when you’re finished here,” I said.

“Sure I will;I promised you I would. Just give me a hand; we’ll be through in a minute,” he answered.

For an endless time, I loaded flotsam and jetsam into his pick-up. The November sky was closing in with the shame of the doomed boat and the gloom of Terry’s mood. “Why am I doing this?” I kept asking myself.

At 12:15, Terry declared the job done. “Thanks alot,” he said. “I’ll meet you at your place in ten minutes. I just want to stop for a brew. I was losing him again. “Listen, I’ve got a full case at home in the fridge,” I pleaded. There still might be time, if we could keep the water at just the right temperature, and forget about the feet and heads, and if Jonah could stay over at the Coxes…

“Oh, that’s all right; this wont take long,” he answered, over his shoulder. I followed him into the pub.

As Terry disappeared into the washroom, my eyes scanned the beer parlour nervously. I was too agitated to banter with the local regulars. Then I spied Emil Krompocker’s benign smile in the corner, above a table covered with empty glasses. For the last three weeks he had been promising to come and fill the deepening ravine in the driveway with a couple of loads of gravel. I zeroed in on him, and forced a greeting:

“Hi, Emil,” I said. ” I’ve been trying to get a hold of you.”

“Yeah. I just got my truck running again. I’ve got this job to finish for Roy, and then first thing I’ll get you your gravel. You know, ‘Jack Bald could probably do a better job; he can use the spreader up at Russ Wilson’s place.”

“I thought your truck could spread the gravel. Are you saying I should get someone else to do the job?”

“I’m not sayin’ that, but maybe it would be a good idea.”

Walking over to an empty table by a window overlooking the gas dock, I ordered two drafts. I thought of the water I left coming to a boil. And of the pigs; ravenous, furious, waiting.

Terry came out of the washroom, sat down, picked up his glass, took a small sip, looked at the clock, looked at me, looked away.

“You’ve got one pig, eh?”

“No, Terry, two small ones, just like last year. About 200 pounds each. Remember?”

“How many helpers do you have for scraping?” “None. We didn’t need any last year.”

“Yeah. If we had a few people to help, that’d make it an awful lot quicker. You see,I have to go to this party tonight. Before that I have to unload all the gear on my truck. Then I have to come back to Lund for a shower. That means I only have until four thirty.”

“You could bathe at my place, and if it’d give us another hour, I could run you into town. How about meeting your friends a little later?”

“Nope, they want to leave by six.”

“I see. Listen I work in town all day and night Tuesday and Wednesday. Thursday, Friday and Saturday I have to go to the Island. How about making it tomorrow or Monday?”

“I doubt it. I stay in town Sundays and Mondays. I guess it’ll have to wait. I didn’t expect this boat thing to happen. I should have called you yesterday. I just didn’t get around to it.”

“Right,” I concluded the conversation. I gulped down the green beer and stalked out of the pub. My new Datsun station wagon looked gaudy parked next to the overflowing garbage truck.

The muffler dragged on the rocks in the puddle at the front of the driveway. As I got out of the car, I was greeted by a hysterical chorus of grunts, squeals and howls. I growled back. The only food I’d had all day was a rushed bowl of granola at 6:00 a.m., and I was crashing off the beer.

The sky was getting darker grey and even closer. I didn’t know if the cloud cover was thickening or if it was just that evening was starting at 1:30 in the afternoon. The water in the barrel was steaming, but the fire in the Ashley heater had been choked by the clogged stovepipes, and the house was cold and clammy.

I grabbed the wheelbarrow and headed for the garden. The path was turning to mud. The goats were chewing on the pear tree bark again. Their hooves were in desperate need of trimming. White mold was flowering on the edges of pruning wounds in the orchard. A spread of green moss was erasing last year’s paint job on the barn. The lid of the compost box lay decomposing where the bear knocked it off last spring.

I hadn’t entered the garden for weeks. The last time was to pick the frost-killed corn for the pigs. “There must be something for them down here now,” I thought.

Behind the gate was a shambles. Tousled asparagus fronds sprawled in the dirt, their fractured stalks protruding from the rows. Dark papery skeletons of the bean plants danced around their poles. A rake and a hoe leaned against the fence, their handles blackening with absorbed moisture. Unripened cherry tomatoes lay exposed in obscene clusters, the same yellow-brown color as their foliage. A swelling billow of chickweed engulfed what was left of the strawberry plants and the slug-infested brussel sprouts. The old stripped broccoli stalks extruded hundreds of tiny heads, some rotten to the touch, some firm.

Grudgingly I broke off a few for our dinner that night and dropped them into a cracked plastic bucket. Still glutted with October’s harvest, I would take no more to freeze. Those were for the pigs. I yanked two dozen of the decrepit plants out of the ground and dumped them into the wheelbarrow, muddy roots and all.

Crossing the decaying bridge I had built with the help of neighbors when we first arrived at the farm, I watched the mist coalescing in the lower pasture. The spindly alders that had recently started reclaiming the cleared land for bush looked like the ghostly spears of an invading legion. I stopped, set down the wheelbarrow and stood dead still. Words uttered themselves without my volition: “God, I’m sick of being a failed farmer. If we burned down the house, collected the forty thousand insurance and sold off the land for another twenty, we could buy a condo in North Vancouver and make a brand new start.”

It was a ridiculous idea, but saying it seemed to relieve some tension. I unloaded the wheelbarrow in the pigpen, kicking with my steel-toed boots to fend off the grovelling snouts. While the pigs mangled the broccoli, I climbed up into the fruit tree they had almost demolished and shook the lichen-grizzled branches until it hailed apples. “That should last them till tomorrow, when I can borrow some grain,” I reassured myself.

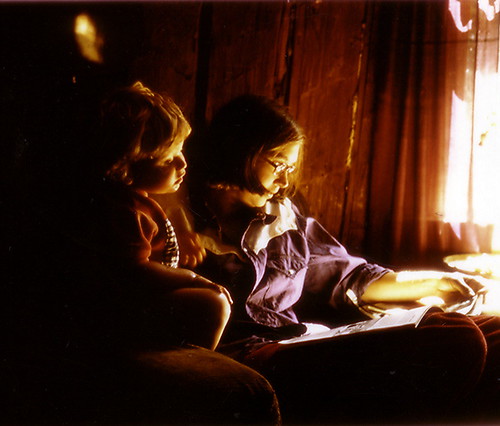

I carried the bucket back to the house, where I dismantled the stovepipe, reamed it out and reassembled it. Once the stove was going I was at least back to square one. I needed to forget those poor creatures I couldn’t finish with, but there wasn’t long enough to start on another project before picking up Jonah. I wished I had him there and then, filling up the time with demand.

With my boots still on, I sat in the rocker and picked up the new book lying on the doily-covered barrel. The title struck me with a shock of recognition: Apple Bay. It was the story about the commune upcoast that Paul Williams was working on when he stayed with us at Christmas, in his spare time fomenting sexual chaos and marital crisis. But that was six years earlier, and fortunately I hadn’t seen or heard from him since. Occasionally, however, I still dreamt of our fistfight in front of the Lund cafe and wished that it had actually taken place.

“Stan must have left the book for me,” I thought. ” I know he’s one of the main characters in it.” Bracing myself, I started to read. But instead of being jolted, I found myself bored. There was neither description nor narrative, just a gushy expression of the author’s

oscillations between self-infatuation and self-loathing. “Why am I reading this?” I wondered. It was embarrassing. A morbid curiosity kept me turning the pages, looking for situations I remembered, people I knew. The phone rang. A welcome interruption.

“Hello. This is Paul,” said a familiar, conspiratorial voice. I’m calling from California.”

The book dropped to the floor. I felt as if he’d caught me peeking into his private diary. The satisfaction he’d get, to know what I was reading, And he’d glory all the more if I told him what I thought of it.

“Paul who?” I asked in a flat tone. “Paul Williams. It’s been a long time.”

“Hello, Paul.”

“I’m going to visit Galley Bay next week, and I’d like to stop and see you and Janet.”

“When are you coming?”

“I’ll be in Lund Thursday and Friday.”

“Jan will be here. I’ll be at a meeting in Nanaimo.”

“I see. Do you know where Stan is?”

“He’s been living on this farm; has been for two years.”

“That’s great. I want to see him. Galley Bay is up for sale for a quarter of a million dollars. I’m going to tell the Real Estate agent I’m a prospective buyer, and get a free ride up there. I want Stan to go with me.”

“I’ll give him the message.”

“Hope I’ll see you on my way back.”

“O.K. Goodbye, Paul.”

“Goodbye.”

As I hung up the phone, I felt a balance restored in my endocrine system. I remembered what it was like to really go crazy. Coincidences abound and you don’t eat. I went to the fridge and started to fix myself a glass of goat’s milk and a large cheese sandwich, with sprouts. I carried the food and a pad and pencil back to the rocker. Between mouthfuls, I wrote out a list:

get j. early

play Lego

pumpkin pies

bath j.

supper – broccoli omelette

chores

phone jan

typewriter

When I reached the door, I stopped to listen. The pigs were quiet.